Author Q&A

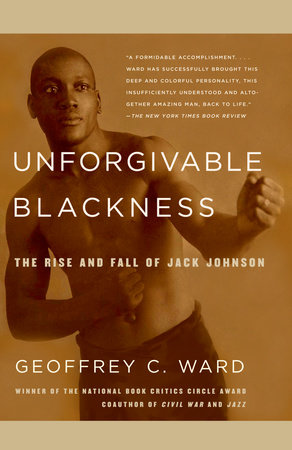

Q:Could you tell us where the title, Unforgivable Blackness, comes from?

A:It’s from a 1914 editorial by W. E.B. Du Bois in which he tried to account for the vicious hostility directed toward the heavyweight champion by so many white people. Johnson was a fair, sportsmanlike fighter, he said, and his morals were no worse than those of celebrated white athletes. The only reason he could find for what he called “this thrill of national disgust’ was Johnson’s race. “It comes down then, after all,” he wrote, “to this unforgivable blackness.”

Q:Jack Johnson might have avoided much of the trouble he found himself in if he had not fraternized with or married white women. Why do you think he refused to do that?

A:Jack Johnson recognized no limits imposed by others. He embodied American individualism in its purest form; nothing – no law or custom, no person black or white, male or female – could keep him from doing what he wanted to do. “I have found no better way of avoiding race prejudice,” he once said, “than to act with people of other races as if

prejudice did to exist.”

Q:What about Johnson’s life fascinated you the most?

A:I wanted to understand how a black man with only a fifth grade education, born to former slaves in post-Reconstruction Texas and growing to manhood in a white-run world in which black inferiority was taught in schools, preached from pulpits, reiterated on editorial and sports pages, could have determined to ignore it all – and managed to get away with it, a least for a time. No one can ever fully explain it: like Lincoln and Edison and Louis Armstrong, Johnson was wholly self-invented. But Unforgivable Blackness does include a wealth of detail about his rise that has appeared nowhere else and shows how extraordinary Johnson was.

Q:In 1908, Jack Johnson became the first African-American to win the heavyweight championship and one of the most controversial figures of his time. Yet, many outside of boxing circles have never heard of him. Why do you think that is?

A:Sadly, Americans have short historical memories. I think also that the racism that permeates Jack Johnson’s story remains an embarrassment to us – at least it should be an embarrassment. But I hope people who read the book will get a greater understanding both of this flawed but amazing man and of the complex country which mistreated him but also made it possible for him to use his gifts and grit to make himself the most celebrated black man on earth.

Q:Some black people, including Booker T. Washington, were almost as critical of Johnson as whites were. What were his feelings about this? Did he ever feel betrayed?

A:Johnson was a realist. He delighted in being a hero to millions of African Americans, but he never wanted to be a racial role model or a civil rights spokesman. At the height of his popularity among blacks –after he defeated Jim Jeffries, the Great White Hope, at Reno in 1910 – he said he hoped they would stick by him but feared that like the French who had turned against his hero, Napoleon Bonaparte, they would desert him when times got lean. He did resent the preachers and politicos who tried to tell him how to live his life.

Q: Patronizing white sportswriters routinely stereotyped Johnson as ignorant as well as “uppity.” It’s clear from your book that he was nothing of the kind.

A:Johnson was enormously intelligent and intellectually curious. He held three patents, played the bass viol and never went anywhere without his Victrola and stack of classical records. He studied the life of Napoleon (with whose rise to power from total obscurity he identified), and wrote – or helped to write – four autobiographies. He was also so skilled at negotiating for his own fights (something few fighters, black or white, have ever been equipped to do) that prominent white managers shrank from facing him over the bargaining table.

Q:You are presently part of a committee working to have Jack Johnson exonerated. If you are successful, he will be the second man to have been pardoned post-humously. What would you say are the strongest arguments for this happening?

A:I drew extensively on Johnson’s Justice Department files to show that his conviction for violating the Mann Act in 1913 was racially motivated — and that his own efforts to obtain a pardon were crushed by government bureaucrats who knowingly made further false allegations against him. That sort of injustice, it seems to me, should not be allowed to stand.

Q:You also wrote a documentary of the same name which will air on PBS next year. How did that process differ from that of writing the book?

A:I love writing documentaries. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have worked on so many of them over the past twenty years. But for me there is nothing quite like making the sort of historical discoveries you can only experience when digging deep into biographical materials for a full-scale book, nothing to compare with making one’s way down corridors where no one else’s footsteps have sounded before. Writing Unforgivable Blackness provided me with plenty of that kind of excitement, especially when I began to work my way through the never-before-consulted autobiographical manuscript found among his prison papers at Leavenworth. I had no idea when I began this book that Johnson would be such an eloquent spokesman for himself.