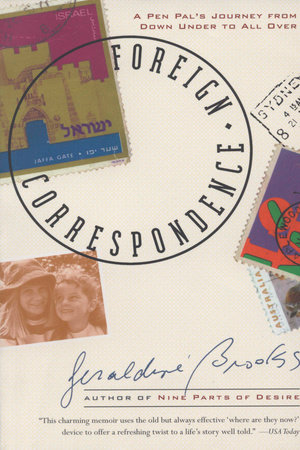

Foreign Correspondence Reader’s Guide

By Geraldine Brooks

1. Discuss Brooks’ choice to structure the book in two parts, and not to tell the story in straight chronology. What are the benefits of these choices? Are there any drawbacks?

2. In what ways did the geography of place affect Brooks?

3. Brooks was an outsider, a loner, an observer–as shown by events ranging from her childhood rheumatic fever, which often separated her from schoolmates, to living "down under," to coming of age on the cusp of the feminist movement. Is this feeling of "otherness" essential to a writer? To this writer?

4. Brooks writes, "In every urban family’s history, there is a generation that loses its contact with the land." Do you think there is more dissonance between the generations that are on either side of this loss than there is to generations further away from it? Can you pinpoint the time in your family history where your family lost contact with the land? How has it affected your family?

5. Australians have an instinctual need to leave their island and explore the world. Discuss this as a theme in Brooks’ memoir.

6. Australian men have a deep and particular relationship with their male friends, their mates, as described by Brooks and others. Compare and contrast this with the idea of women’s friendships in the United States, which are often cited as different and deeper than men’s friendships.

7. Discuss Brooks’ religious upbringing and why you think she converted to Judaism. Did her childhood experiences foreshadow the conversion to come?

8. Brooks comes to a gradual realization that Australia is not so small a place after all. How does this compare or contrast with American myths of exploration and home?

9. In what ways does the Australian "Cultural Cringe" syndrome mirror the more personal cringe that many children, especially teens, feel about their parents and their brothers or sisters?

10. Brooks writes that she "had more years of shared confidences with Joannie than with any of my mates in Sydney." Would their relationship have been less important if they had not developed it through writing only? In what ways? In your experience, does the act of writing letters make a friendship stronger?

11. Do you think e-mail has changed the pen pal experience for kids? In what ways?

12. Assume you have to choose one or the other, which is preferable–to grow up in a restricted environment with no car, with no travel, and with curfews and strict limits? Or to travel widely and experience many different cultures and have more responsibility and opportunity at an earlier age? Talk about the benefits and drawbacks of each.

13. Discuss Brooks’ identification with Joannie–her observation that she’s living the life Joannie was meant to lead.

14. Does Brooks follow or disregard (personally and professionally) the advice she received from a veteran correspondent, "Never get in the middle. You have to choose your side." How does the author feel about the middle?

15. When Brooks is in the French village of St. Martin, visiting Janine, do you suspect that she will ultimately identify so strongly with her?

16. Brooks confesses that she felt an "inevitability" about leaving Australia. Do you also think it’s inevitable that she’ll go back and live in Australia with her husband and son?

17. Brooks’ father kept secrets from her for a long time. How might she have felt if she learned about her father’s other daughter at an earlier age? Do you think he made the right choice in keeping it from her for so long?

18. Talk about the "happiness set point." In what ways do you essentially agree with or question this theory of human behavior?

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In