Author Q&A

Q: Only several years ago you were in and out of the hospital, struggling with various addictions and with mental illness. You thought you might die and were sure you’d never write again. How did this new collection come into being?

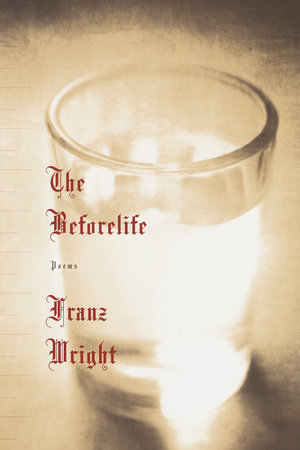

A: In the winter of 1998 I was still suffering from a psychotic and delusional depression from which it seemed unlikely to me (and to doctors I’d managed to consult) that I would ever recover. I was suddenly reunited with a young woman I had been in love with for over ten years, one who agreed to marry me, and quite literally gave me back confidence in my ability to go on living and trying to write. One evening on my way to see her I had the experience I would later try to describe in the poem "Thanks Prayer At the Cove,” which is coming out in the Fall 2000 issue of the journal Field. To me this is the book’s central poem, though I had to write a lot of others and move around a bit before the possibility of writing something about this kind of experience ever occurred to me. By the time it did, in November 1999, in Waltham with Elizabeth, I was writing poems with a kind of dream speed or ease utterly unprecedented in my life. The poems of The Beforelife were written in one year, but they were the first poems I had written in nearly three.

Q: In poems like “Written With a Baseball Bat-Sized Pencil” you describe the touching, lost characters you met when you were hospitalized — the people, you write, “who aren’t coming back.” Did you learn anything from these people? How does their presence figure in your poems and in you thoughts?

A: I feel an allegiance to those who are suffering from mental illness at different stages of despair and, sometimes, return from it. I shaped my previous book, one of selected and new poems called Ill Lit, as an attempt to give a voice to conditions or states of mind normally associated with speechlessness, and that impulse continues in The Beforelife, perhaps even more consciously.

Q: How would you define what you call “the beforelife”? It seems to refer to an in between space, a time between illness and health.

A: I am hesitant to explicate my title. I suppose it can be interpreted in different ways–all at once, I hope. There is of course a purgatorial gravity about it, for me, but also it emits expectation of some kind of light. I think Carol Carson’s very beautiful and inspired cover, based on a photograph by Jane Yeoman, brings out in the title a true sense of image; that is, it presents whoever looks at it with the opportunity to remember that he is capable of inhabiting simultaneously different levels of sensation and thought, that this mysterious and maybe perilous pleasure is available to him. It suggests there is a connection between things or experiences which appear on the surface to exclude one another.

Q: You’ve known great pain, though you’ve described the writing of this collection as rhapsodic. Do you find your inspiration in anguish, or joy?

A: I doubt that it is possible to write anything of value in a state of genuine anguish. And I know that for me writing involves a rapt state of energy and joy. I did not write about dark things when I was going through them (in fact, I have had long stretches of time when such experiences seem to have killed in me the impulse to speak of them, or of anything else for that matter, ever again), but I wrote them because they were what I knew about; and often I think I wrote out of a sense of allegiance to those who are still in so much suffering that they will probably never again find words for what they are going through.

Q: The beauty of your words — the craft of your poems, which are often short and gorgeously precise — stands in stark contrast to the misery you often describe. How do you reconcile your life as both artist and recovering addict?

A: You use the term craft, and craft’s just that, and an objective dedication to it can become a spiritual discipline–one among others–which makes it somewhat possible to confront, endure, and on occasion transcend the various torments any human being is going to encounter in the journey of his or her life. I doubt that anyone can get through this life as a sane person–that is, one capable of love–without spiritual discipline of some kind, and dedication to some kind of work. Or craft, as you say.

Q: The poems of this collection are highly personal. Was it difficult to expose yourself so fully?

A: During the year of this collection I was in a great passion to disclose, but also to make up, or sometimes to hide. Sometimes the poems look to me like little machines which either do or do not work; or they once again, in an instant, become personal-prayers or spells never actually meant for others’ ears.

Q: What role does humor play in your work?

A: Someone writing in Boston Review, in a brief but thoughtful review of my work, recently spoke of a "dark levity" in some of the poems. I think his point was that this quality sometimes saved the poems from becoming what my friend the poet Thomas Lux would call "unremittingly grim." And I think it’s a good point. And in times of great desperation, people do discover this dark funniness. James Tate and Charles Simic are great masters of this, as is Lux – humor is found to be a profoundly spiritual sustenance, either in shocking or nightmarish circumstances, or engulfed in the eerie normalcy where one appears to be safe. It’s as terrible to live without as love.

Q: Your father James Wright, was an acclaimed poet of the postwar generation. How much of his spirit infuses your own work?

A: I always believed my father was a great poet, and that belief only intensified as I got older and we became rather close–through correspondence mainly, but also during memorable visits, in my mid-teens and early twenties. My parents were very painfully divorced when I was eight, but even from the distance of a couple thousand miles, or the entire breadth of the country, he and his books remained a powerful presence to me. But I think it is probably difficult for anyone not born at least in the 50’s to recall how much his books meant to practically everyone who loved poetry in the 60’s and throughout the next decade until his death in 1980. I think he continues to be present in the life of American poetry. His collected poems is such a magnificent gift to the world. There are instances of holiness in his work, an immense compassion and love for the entire creation, which people are going to go on discovering.

Q: In poems such as “The Dead Dads” and “Primogeniture,” your father has a powerful presence. Does he haunt you more as a poet, or more as a certain kind of father?

A: I don’t think I realized until my mid-forties, which is the age my father was when I got to know him, that I had some bones to pick with him. Maybe that comes out a bit in this collection; however, throughout my books there is a small thread of poems which speak either about or to him, usually in the tenderest possible way. So there is that as well. I love my father very much, and believe he was an extraordinary man, a very great man.

Q: Where would you place yourself within the larger world of poetry?

A: I don’t have the faintest idea of where I would place myself in the larger world of poetry. My dad’s idea was that people discover poems they need, in secret–and in my experience that is certainly true. If one can add a poem or two to that place of great poetry, where people sometimes go for a form of sustenance nothing else in the world can provide–if one can be a part of that, or an instrument of it now and then, one can only be amazed and grateful.

Q: You dedicate this collection to your wife, who you credit with helping you put your life back together. Is “Description of Her Eyes” written about her? Are there any other poems in the collection that are written for her?

A: "Description of Her Eyes" is indeed about my wife Elizabeth, and it changed for a while as we moved from place to place in 1999. But the whole book is addressed to her–sometimes openly, or when not, it comes out of a general spirit of gratitude for her presence, without which there would have been no book.

Q: I’ve heard that you work with grieving children and other support groups. Could you tell us a little about what this work means to you?

A: I am a volunteer facilitator at The Center for Grieving Children in Arlington, part of a group of other facilitators working with 8 and 9 year old children who have recently lost a parent. I don’t know what to say about this, except that very few experiences have ever made me happier, or made me feel more connected to other human beings.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: Right now I have a little limited edition book of twenty new poems about to come out from Half Moon Bay Press in Michigan. And the poems are from a larger body of new poems which were primarily religious, initially, but which are now starting to branch off in still unpredictable ways.