I'd Like to Apologize to Every Teacher I Ever Had

By Tony Danza

By Tony Danza

By Tony Danza

By Tony Danza

-

$20.00

Sep 03, 2013 | ISBN 9780307887870

-

Sep 11, 2012 | ISBN 9780307887887

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

The Five-Forty-Five to Cannes

Adrenal Transformation Protocol

Royal Affairs

Murder On Monday

The Habitat Guide to Birding

The Next Fifty Years

The Invisible History of the Human Race

The Parrot’s Lament

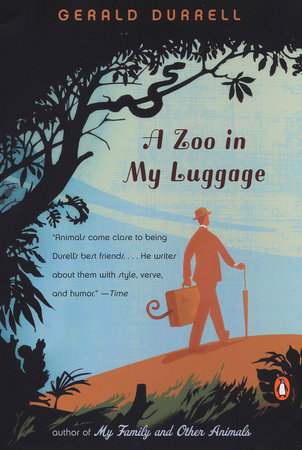

A Zoo in My Luggage

Praise

“Breezy…Danza is able to shed light on a number of the underreported struggles teachers face.”

–Booklist

“In this endearing memoir, Danza defies expectations…[filled with] refreshing honesty…provides insights into a teacher’s daily life.”

–Publishers Weekly

“A witty, self-deprecating, and charming account of how being a teacher extends far beyond the four walls of a classroom. From sweating through his shirt to harboring adoption fantasies, Tony Danza depicts his brutally and beautifully real experience as a first-year high-school teacher. With humor and honesty, he highlights the emotional toll of teaching and describes how one of the most important careers in America is still one of the most unappreciated.”

–Erin Gruwell, author of the #1 New York Times bestselling The Freedom Writers Diary

“At age 59 Tony Danza inexplicably chose to become a teacher at a tough, inner-city school. The story he tells is moving, eye-opening, and compellingly honest. Love infuses his work, and he cries a lot. Read this book and you will too.”

–Joel Klein, former New York City Schools chancellor

“It takes a lot of courage to stand in front of a group of teens and proclaim yourself their teacher. It takes even more to be a good one — someone who sees each student as an individual with a unique life story. Tony Danza put himself forward to teach children and learn from them, knowing that the more he really understood these kids the better teacher he could be for them. We easily forget how truly difficult it is to be a transformational teacher and in these pages you can see that’s what he became.”

–Rosalind Wiseman, New York Times bestselling author of Queen Bees & Wannabees

“Tony Danza is filled with life, joy and the spirit of altruism – which makes him a natural teacher, as well as a perfect witness to the victories and tragedies in today’s inner-city classroom. Like teaching itself, this book is an emotional roller-coaster – but it’s also a sobering account of the perilous state of schools in our poor communities. This is a must-read for anyone who cares about the future of the nation’s children.”

–Geoffrey Canada, President and CEO, Harlem Children’s Zone

“I highly recommend I’d Like to Apologize to Every Teacher I Ever Had to everyone who has thought about teaching as an encore career – and anyone who wants to know what life is like for teachers and students in American public school classrooms today. Tony’s book will make you laugh, cry, and cheer. It serves as a call to action for every one of us to take a stand and commit to the education of our young people.”

–Sherry Lansing, Former CEO of Paramount Pictures and Founder of The Sherry Lansing Foundation

“A great antidote to all those pieces by folks who consider teaching glorified babysitting.”

—Library Journal

Table Of Contents

Preface

FIRST SEMESTER

1. You’re Fired, Go Teach

Teachers Lounge: Lesson Plans

2. Ignorance Is No Excuse

Teachers Lounge: The Real Deal

3. Do Now

Teachers Lounge: Everybody Cries

4. The Half-Sandwich Club

Teachers Lounge: Bobby G

5. Making the Grade

Teachers Lounge: No Fear Shakespeare

6. Never Smile Before Christmas

Teachers Lounge: Northeast’s Got Talent

SECOND SEMESTER

7. Field Tripping

Teachers Lounge: Gone Bowling

8. Poetic Justice

Teachers Lounge: Happy Hour

9. Our Atticus

Teachers Lounge: Adequate Yearly Progress

10. Spring Fever

Teachers Lounge: Fight Night

11. Finals

Teachers Lounge: The Sons of Happiness

12. If…

Teachers Lounge: Saving Starfish

EPILOGUE

Acknowledgments

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In