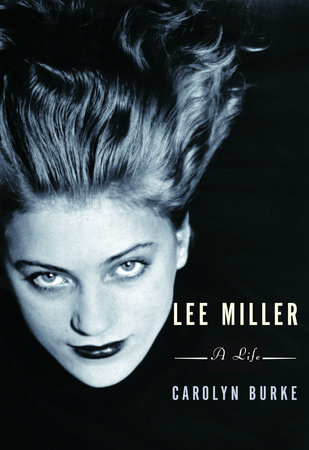

Lee Miller

By Carolyn Burke

By Carolyn Burke

By Carolyn Burke

Read by Ann Richardson

By Carolyn Burke

Read by Ann Richardson

Category: Arts & Entertainment Biographies & Memoirs | Photography

Category: Arts & Entertainment Biographies & Memoirs | Photography | Audiobooks

-

Oct 06, 2010 | ISBN 9780307766632

-

Jan 26, 2021 | ISBN 9780593401958

1129 Minutes

Buy the Audiobook Download:

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Return of a King

Crusader Gold

Tibet, Tibet

The River Cottage Meat Book

Absolutely American

Death of a Jewish American Princess

Punch

Three Cups of Tea

The Reformation

Praise

“A biographer couldn’t ask for a more compelling subject, and Lee Miller couldn’t have asked for a more insightful and eloquent biographer. Carolyn Burke writes with lucidity and energy. As adept a storyteller as she is an ardent scholar, she is generous with details yet never gets bogged down. Fluent in the nuances of ambiguity and cued to the obdurateness of paradox, she provides thoughtful and measured analysis that is genuinely enlightening and never intrusive . . . Miller’s story of personal reinvention and artistic evolution blazes right along, and Burke feeds the flames with just the right mix of straight-ahead chronicling and shrewd commentary, steering the reader to the apex of Miller’s life, her courageous and artistic response to World War II . . . No one who reads Burke’s involving biography will ever forget Miller. So visually rich and electrifying is her story, a movie version seems inevitable. But whatever interpretations the future may bring, Burke’s vital and incisive portrait will be the wellspring. Demonstrating the same clarity of observation and sensitivity to subtleties that distinguish Miller’s photographs, Burke indelibly portrays a radiant woman forced to look into the heart of darkness, and an artist who cast light on a brutalized world, illuminating its abiding beauty and grace, and enhancing our empathy and awe.”

–Chicago Tribune

“Delightful, meticulously researched, fascinating . . . [Miller] was a woman who needed no exhortation from anyone to “Live! Live!” Her life was filled with adventures . . . Miller’s life had many phases, all of them interesting, and Burke captures them in [this] fine biography.”

–Washington Post Book World

“Compelling, riveting . . . It seems fitting that Carolyn Burke, whose first biography corrected history’s error of undervaluing the avant-garde poet and artist Mina Loy, has written Lee Miller: A Life. [Miller is] a forgotten visionary photographer who was muse and lover to some of the most influential artists of the early 20th century, as well as one of the few women able to transcend this role and become an artistic force in her own right . . . The photograph that may give the truest glimpse into Miller’s nature is a portrait shot in Hitler’s bathtub . . . A woman caught between horror and beauty, between being seen and being the seer.”

–New York Times Book Review

“At last, a life and an album about Lee Miller, one of the most beautiful women who ever lived . . . A remarkable book . . . [Burke] lets the facts speak for themselves. And the facts are vivid . . . For the first time the ravaged arc of Lee Miller’s life is clear, beautiful but lined in pain.”

–New York Observer

“Fascinating, remarkable, memorable . . . [A] singular life . . . It’s one of the great joys of reading: a story about someone you’ve never heard of, giving you insight into something you didn’t know you cared about. That’s the gift from author Carolyn Burke . . . A captivating read, one that raises questions in the reader’s mind about how things have changed–and how they’ve stayed the same–in women’s lives over the past century . . . Burke’s book is what biography ought to be . . . Lee Miller: A Life belongs on the shelf of anyone interested in how people of [Miller’s] generation dealt with their times.”

–Santa Cruz Sentinel

“[Lee Miller’s] peregrinations reminded me of innumerable others’–Lillian Hellman, Martha Gellhorn, Rebecca West, and Jill Craigie . . . [But] of all the women I have in mind, Miller strikes me as the most heroic. [Miller’s photographs] dramatize art and history, making both more accessible . . . Burke brilliantly draws on Miller’s own history to understand the photograph [of Miller in Hitler’s bathtub]. Gellhorn, Hellman, West, and Sontag never acknowledged just how self-conscious they were about writing themselves into the world’s consciousness. Miller is their superior in understanding what it meant to model yourself after others in order to make yourself the next model . . . Miller was an exceptionally honest artist-observer, one who knew just how deeply implicated she was in her scenes . . . This handsomely produced and impeccably written and researched book is surely a state-of-the-art biography.”

–New York Sun

“Illuminating . . . As a disciple of Alfred Steichen and devotee and lover of Man Ray in Paris, [Miller] played the ingénue a little but was more knowing than all that; indeed, she recalled, she was a bit of a fiend. Ray came eventually to regard her as a threat, though it was likely for the ever-deepening quality of her work as a photographer. [She] had the kind of life that the present-day bohemian can only aspire to; yet Miller fully came into her own as a combat correspondent (for Vogue) in Europe during WWII . . . Burke’s graceful biography restores Miller to attention; students of art photography, in particular, will want a look.”

–Kirkus Reviews

“Those who knew [Miller] say that she always provided an intriguing study in contrasts. A model-turned-photographer-turned-war correspondent, she later added gourmet chef to that list of hyphenates. In her world, a closetful of Vionnet gowns and combat boots made sense . . . Unlike other books on Miller, which consist mostly of photographs, [this] is a thoroughly researched account of her life [and] remarkably diverse accomplishments . . . Miller’s life unwound like a mad Surrealist film–the cast of characters and roles she would play were wildly colorful and made for quite outré stories . . . She had lived, by the end, many extraordinary lives . . . Captivating.”

–W magazine

“[Miller’s] surrealist background led her to taking stunning photos of the London Blitz, but she shot her most memorable–and disturbing–images accompanying American troops from Paris to Dachau as a war correspondent for Vogue. Burke’s meticulously detailed biography reveals how keenly Miller’s wartime experiences haunted her during her final troubled decades, but it also probes sympathetically into the artist’s other significant trauma . . . Burke writes with a careful sense of how Miller might have approached her work and of how it is perceived by modern viewers. Her descriptions of Miller’s imagery are so vivid that, despite the dozens of photographs reproduced here, readers will find themselves wanting to see more. As the first major biographer outside the Miller family, she traces a dynamic life that embodies the spirit of the 20th century’s first half.”

–Publishers Weekly

Praise from the UK:

“Superb . . . Just as Miller lived what seemed like 10 lives, so Burke has done enough work for 10 books. The effect is never stifling, however. [Burke] never let[s] a good tale slip by. She is the ultimate photographer’s assistant: setting up the background against which her subject can shine, clever, capable, sympathetic, and never in the way.”

–The Herald

“[Miller’s photographs] are hard to forget. Until relatively recently, however, Miller’s fame, as a flawless beauty, photographic collaborator and model, overshadowed her artistic legacy. This first full-length biography . . . shows how Miller’s complex nature contributed to this neglect . . . The biography truly comes to life when [Miller] became a war correspondent . . . Carolyn Burke’s sympathetic tribute sheds further light on the lives of this highly original, often misunderstood woman.”

–The Economist

“Meticulous . . . Lee Miller was an astounding woman, brought memorably to life in this astounding book.”

–The Telegraph

“Illuminating, revelatory, perceptive . . . A welcome and long overdue biography sure to become essential reading for any student of the history of art and photography in the 20th century. [Burke] strips away the myth to uncover not only Miller’s artistic achievement, but her true character . . . Such is the subtlety of Burke’s approach to her subject that almost by stealth the reader becomes aware, in a similar way perhaps in which it dawned on the young Lee Miller herself, that she was destined to be something special. [Burke writes] with poignant acuity [and] bring[s] her subject to life . . . [Lee Miller: A Life] reads not only as serious biography but often like a picaresque novel . . . More than a biography, this book provides a rare and valuable sideways look at the mid-20th century avant-garde and high-society . . . It takes the reader deeply and unforgettably into the psyche of the strange little girl from Poughkeepsie who grew to become one of the most extraordinary women of her time.”

–The Scotsman

“There are the rare artists who lead not just one, but a whole fistful of remarkable lives, any one of which might make a juicy feature film, crammed with sex, danger, celebrity and fun. At which point, cue Lee Miller . . . [Lee Miller: A Life] does its complicated subject more than justice, adding welcome depths and nuances to the familiar legend . . . Burke relates all this with sympathy and fluency.”

–Sunday Times

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In