READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

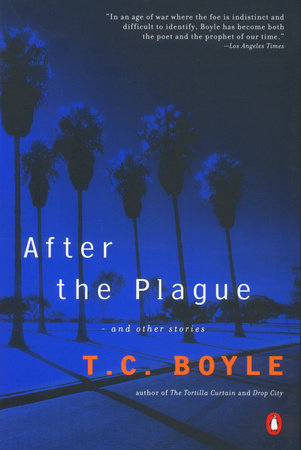

T.C. Boyle is a writer who composes his stories in the way a magician performs his tricks, with an abundance of dazzle and sleight of hand. And yet, above all, he draws the reader into his world with arresting and often irrational characters, strong plots, and his trademark lyricism. There are few writers today who combine his sheer storytelling power with such poetry. But that is only the beginning. What makes these stories so affecting is their social consciousness—Boyle holds up our evolving behavior to the light of analysis and to drama, satire, and comedy, demonstrating his range here in any number of voices and modes. These stories are very different from anything you will have read before, each story distinct from the one that precedes it, and each of them breaking new fictive ground. They are gripping, dramatic, and hilarious by turns.

The social concerns reflected here were, as many readers will know, prefigured in Boyle’s recent novels, A Friend of the Earth, which dealt with environmental issues, and The Tortilla Curtain, a book that focuses on illegal immigration and has been celebrated as a Grapes of Wrath for our time. Some of the stories in the present volume feature behavior pulled directly from the headlines, such as “The Love of My Life,” in which two high school sweethearts, who “wore each other like a pair of socks,” deal with the birth of an unwanted child by abandoning it in a Dumpster, and “Killing Babies,” which addresses the abortion issue through the thoughts and actions of a recovering drug addict employed as a grunt in his elder brother’s abortion clinic. This growth into social and political works seems a natural progression for Boyle. As he matures he seems to have become even more aware of world issues, often skewing his satirical outlook to contemplate an issue that is particularly close to him—abortion and teenage pregnancy in the case of the aforementioned stories—but also our environmental crises and the ever widening gap between the economic classes.

Yet throughout his career, Boyle has always been fascinated with the relationships that humans carve out of each other—how they evolve, and how they ultimately stay the same. There is no lack of such character-driven tales in After the Plague. In “Rust,” an elderly married couple forced to come to terms with the inevitable end of their lives together feel both a grim sense of fear and, oddly, relief. “My Widow” lovingly imagines the author’s wife after his own death (“my widow is smiling, her face transformed into a girl’s, the striations over her lip pulling back to reveal a shining and perfect set of old lady’s teeth”), but instead of granting her the serenity of old age, he pictures her as a lonely old cat lady being preyed upon by a vicious con artist.

Yet, it is the title story, “After the Plague,” that marks Boyle at the very top of his form, in a simultaneously charming and arresting look at what would happen if you were among the very last people on earth (“I knew there wouldn’t be much opportunity for dating in the near future, but we just weren’t suited to each other”). A work that cannot easily be categorized, and unquestionably one of the most effective of the collection, “After the Plague” blends human idiosyncrasies with critical social analysis, allowing the reader to laugh at his or her own weaknesses while being thankful that none of us (by any stretch of the imagination) can be as grotesque or irrational or downright human as Boyle’s rich characterizations make us out to be. Or can we?

T. C. Boyle has always been at the forefront of contemporary American fiction, and After the Plague shows him at his most prescient, delineating and examining not only the way we live today, but what our behavior portends for the future as well. These are stories that beg to be read aloud, stories that resonate in the way of the tales told round a campfire. Enjoy.

ABOUT T.C. BOYLE

T.C. Boyle is the bestselling author of After the Plague, T.C. Boyle Stories, Riven Rock, The Tortilla Curtain, Without a Hero, The Road to Wellville, East Is East, If the River Was Whiskey, World’s End (winner of the PEN/Faulkner Award), Greasy Lake, Budding Prospects, Water Music, and Descent of Man (all available from Penguin). His fiction regularly appears in major American magazines, including The New Yorker, GQ, The Paris Review, Playboy, and Esquire.

A CONVERSATION WITH T.C. BOYLE

You are very well regarded as an author of both short stories and novels. Could you talk a bit about the process you use to write each? Do you approach a short story differently than you would a novel? If so, how do these approaches differ? How do you determine whether an idea will form a short story or a novel?

Well, to begin with, I have to say that I consider myself a very lucky individual in that I spend as many as four or five hours a day in a dream-state—and I get paid for it too. Mon Dieu! Formidable! Stories are the foundation and backbone of my life, and I can’t really say why that is, but I can tell you that my deepest thinking and my greatest pleasure derives from creating stories, from putting one semantic block atop another until something clicks and the piece is finished. And you’ll notice that I use the term “stories” here—that is because I make no distinction between novels and short stories, except that the novels are more complex and take more time and space to work out. As many readers will know, I began as a short story writer and perhaps published as many as thirty or forty stories before I turned my hand to my first novel (Water Music, 500 pages of stories all threaded together in 104 chapters).

You begin this collection of stories with the following quote from Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary: “Language is like a cracked kettle on which we beat our tunes to dance to, while all the time we long to move the stars to pity.” Why did you choose this particular inscription? How does Flaubert’s description of language relate to your own understanding of the word?

Since it’s not really the place of the writer to interpret his/her own work, I think I’ll leave this to the reader’s imagination. Study the Flaubert quote. What does it say to you apart from the stories it introduces? Now read the stories, and finally, go back to the quote. Has anyone, ever, found language sufficient to express the emotions that rend us day and night?

“Killing Babies” is a work wrought with the volatile controversy of abortion rights. Initially it appears to be the work of a man who is purely pro-choice. Yet, upon closer inspection it actually does a fair job of presenting both sides of the issue, especially when the protagonist, Rick, executes one of the protestors, effectively lowering himself to the level of those that personally attack and harm abortion providers. What was your motivation for a story like this one? Were you hoping to make a statement regarding your own feelings on the abortion controversy?

I do not write stories with a political message. Any agenda an author may have should be saved for polemics or the campaign trail. I write stories in order to work out my own feelings about a subject, issue, emotion, scenario, and my stance on it must evolve along with the movement and characters of the story, otherwise I would produce false and shoddy goods. I do believe that an astute reader will apprehend precisely where I stand on every issue, but I’m not interested in waving flags. What grabs me about this story—“Killing Babies”—is the moral nullity of its narrator. He knows nothing of issues, only of blood and hate and what team he happens, by chance, to be on. And I love the story for its final lines, which continue to chill me every time I look at them.

The relationship between Achates and his father Tom in your story “Achates McNeil,” although very similar to many young people’s experiences with an estranged parent, have the added conflict of his father’s fame as an author. Does this relationship in any way parallel the relationship that you have with your own family? Also, the character of Tom McNeil shares both your first name, and in some ways, your appearance and mode of dress. Why did you choose to portray the character in this way, especially since Tom McNeil is not the most sympathetic character in the story?

I wrote this story when my children were young, imagining the burdens they might have to carry as the progeny of a famous egomaniac, which is, I suppose, a pretty fair self-description. Do I empathize with them? Oh, yes, indeed—which is why the story is narrated from the point of view of the son. (And no, I’m not the father in the story, but I could have been.)

“The Love of My Life” is quite obviously based on the State of Delaware’s case against Amy Grossberg and Brian Peterson, the two college students charged with murder after abandoning their infant in a Dumpster immediately after Grossberg gave birth in a motel room. What was it about this case that compelled you to explore it in a fictional narrative?

I had heard of the case in passing, as well as another similar case (the Prom Mom) that occurred around that time. As often happens in my stories I began with the why—why might this have happened and what does it mean? I was fortunate with the story, in that it turned out to be one of the gems of the collection, passionate and heartbreaking. We’ve all been in love. We’ve all been in that motel room. And we’ve all made our choices.

In all of your work, the names of your characters seem to be chosen to convey a certain personality trait or quality of the character, such as the character of Hart Simpson in the twenty-first-century love story “Peep Hall.” How much time and thought do you put into this choice? Do these names more often occur to you spontaneously, or do the characters seem to produce their own names as you create them?

Again, such interpretive questions should best be left to the readers of the world. Certainly many of my characters have names that echo or imply something about them, but when this is the case, it is a happy accident (or, rather, the inspiration of the moment). It would seem artificial, I think, to push the characters’ names too firmly in an allegorical direction, unless, of course, allegory is your intention. Better to let them resonate, and seem real.

“My Widow” at first appears to be a fairly commonplace description of an elderly widowed woman and her lifestyle—the ordinary (going to the shopping mall) and extraordinary alike (thwarting a burglary attempt). Yet it’s written with the attentive sensitivity and empathy of someone who truly understands this woman’s situation. Is this merely a composite sketch of an elderly woman, or is it based on an acquaintance of yours? Or is this a case of the author looking into the future to evoke what may happen to your loved ones after your own death?

Are you kidding? A composite sketch of an elderly woman? Again, mon Dieu! I live with her—have lived with her for most of my natural life, at least that part of it after which I was pronounced an adult by the authorities at large. There is love in the story, no doubt, and sweetness too, but it is tempered, I think by a certain satiric edge as well (you will notice that I gave her a second husband…but he doesn’t last long, does he?). The piece first appeared in The New Yorker on Valentine’s Day, and it brought me more mail than any story I’ve ever published. All the people who wrote me chose to see the story in its essential garment of sweetness and concern. And I guess I’d better leave it at that.

In both “The Black and White Sisters” and “The Underground Gardens,” the characters are altering the classical sense of home to suit their own needs, despite being thought bizarre by the (less-enlightened?) population that surrounds them. While it is true that everyone’s home is modified to one’s own needs and specifications, many of the homes that appear in your books are wildly extreme in their modifications. This convention reoccurs in many of your stories and novels, recently manifested as Sierra’s tree in A Friend of the Earth. What is it about this ideal of home that appeals to you? Is your own home infused with your personal philosophy?

Good question. I suppose I am interested in the futility of our lives, in which we alter the environment, raise our children, build our homes, and go to the dentist, only to give it up in a rotting heap of flesh, tied forever to the earth. I know it’s futile. I know everything is hopeless. And yet I can’t help going on, as if I were a character in a Beckett play.

Of late, you’ve had a very strong theme of looming ecological disaster. For example, the world you visualized in A Friend of the Earth was one destroyed by the greenhouse effect and mass extinction of most of the mammal population, not excluding human beings. The world you visualize in the title story, “After the Plague,” is one (nearly) wiped clean of the human species all together. Obviously, this view is not a very optimistic one for the future of the planet. What is your actual view of the Earth twenty years in the future? How about one hundred years in the future? Do you think that our efforts to “Save the Planet” are actually steps taken in the right direction to reverse the damage we’ve done, or is it truly too late for us?

Though the collection in which “After the Plague” appears was published a year after A Friend of the Earth, the story precedes and in a way prefigures the novel. As many readers will know, I have been obsessed with our animal origins, with Darwin, with the environment, from the beginning of my career. (My first collection, published in 1979, was Descent of Man, and the title story opens with the immortal line, “I was living with a woman who suddenly began to stink.” And why? Because she is working very closely with a colony of apes, as a researcher.) So, in short, yes, I am environmentally concerned, and no, I don’t have any hope. With A Friend of the Earth, I went around the world on my book tours, depressing the hell out of people, while at the same time making them laugh, of course. The only hope I could come up with, and this after a long evening of reading excerpts and taking questions, is a program I’d like to initiate. It’s very simple: if we can all of us on the earth, and no cheating, please, agree to refrain from sex for one hundred years, the problem will be solved.

There’s been a terrific buzz about your new novel Drop City. Can you tell us a bit about it?

Yes, there has—more so, in fact, than for any of my books thus far. I don’t really know how to account for that, beyond saying that I’ve put my usual effort, not to mention heart, soul, and seat of the pants into it, unless, perhaps, it’s the era and subject people are warming to. This book is an outgrowth both of the first story in After the Plague (“Termination Dust,” set in Alaska, and it is referenced in Drop City) and A Friend of the Earth. If I went twenty-five years into the future to examine the environment in that book, now, in Drop City, I reverse thirty years to 1970 and the back-to-the-earth movement of that period. Yes, folks: read hippies. The ethic then, when there were a mere four and a half billion of us on earth, was to reject the product—and technology-dominated society we’ve all grown up in and go back to the basics, to live simply, to live off the land in a Thoreauvian way. Was that possible then? Is it possible now? That is what Drop City is about. It takes a group of hippies—the Drop City commune— and transports them to the last and final place on the continent, Alaska, where they come into prodigious contact with the locals, who also desire to live close to the earth. The result, if I’ve got it right, should be a kind of feast for the reader’s imagination.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS