The Fall of Berlin 1945

By Antony Beevor

By Antony Beevor

By Antony Beevor

By Antony Beevor

Category: World War II Military History | European World History

Category: World War II Military History | European World History

-

$22.00

Apr 29, 2003 | ISBN 9780142002803

-

Apr 29, 2003 | ISBN 9781101175286

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Centennial Crisis

The Heart of Hell

Berlin 1961

Stalin

No Quarter

Flights of Passage

The Beauty and the Sorrow

Above the Reich

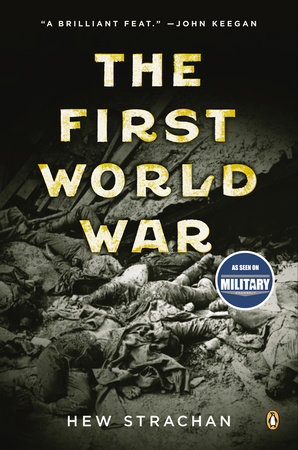

The First World War

Praise

“There was no more hellish place on earth than Berlin in 1944…[and] Beevor has created haunting images of the war’s final days.” —The New York Times Book Review

“Beevor is…a superb writer, a diligent researcher and a master of battlefield detail.” —The Chicago Tribune

“A tale drenched in drama and blood, heroism and cowardice, loyalty and betrayal.” —Jonathan Yardley in The Washington Post

“Antony Beevor is a British historian of great distinction and range, who has written widely on military affairs in the twentieth century. His history of the battle of Stalingrad was awarded the Samuel Johnson Prize for Non-Fiction, the Wolfson History Prize and the Hawthornden Prize for Literature. To write a successor to that excellent chronicle of the savagery of modern warfare could not have been easy. . . But Beevor once more demonstrates his mastery of his sources, including newly discovered material from Soviet archives, and his skill in describing complicated operations.” —Gordon Craig in the New York Review of Books.

“A quite splendid book, one which combines a calm and scholarly narrative with an unrelenting moral indignation at what he has uncovered. It stands as a superbly lucid examination of one of the most dreadful battles in world history.” —Kevin Myers in the Irish Times.

“With [the Red Army] travels Antony Beevor—understanding the wider strategic issues as well as feeling the plight of the simple soldiers of both sides, in this mother of all battles, carrying on his back an imposing pack of research as well as compassion. His majestic earlier book, Stalingrad, equips him to be the essential concomitant to write this final battle.” —Alistair Horne in The Times (London).

“As in his Stalingrad, Antony Beevor skilfully combines the big picture of the developing strategic situation with a sense of the extraordinary experiences on the ground . . . The strength of The Fall of Berlin 1945 is an irresistibly compelling narrative, of events so terrible that they still have the power, more than half a century on, to provoke wonder and awe.” —Adam Sisman in the Observer.

“An impressive contribution. . . packed with stories about soldiers and civilians at the extremes of human experience, Berlin excites and informs.” —The Economist

“In Stalingrad Beevor gave us a riveting account of that crucial fearful battle, when Hitler’s forces met their match. . . Beevor deploys the same successful techniques in Berlin. He combines a soldier’s understanding of war’s realities with a novelist’s eye for symbolic and emotional detail. Nobody will forget the artillerists who kept their mouths open to stop their ear drums bursting as they fired their guns; the little boys in Landsberg who played war games with wooden swords amid the bombed-out ruins of their house; or the rhodedendrons that were coming into bloom as mortar-fire rained down on Berlin, darkening the street with smoke and dust. Beevor paints a terrifying picture.” —Orlando Figes in the Sunday Times (London)

Table Of Contents

The Fall Of Berlin 1945List of Illustrations

Maps

Glossary

Preface

1. Berlin in the New Year

2. The ‘House of Cards’ on the Vistula

3. Fire and Sword and ‘Noble Fury’

4. The Great Winter Offensive

5. The Charge to the Oder

6. East and West

7. Clearing the Rear Areas

8. Pomerania and the Older Bridgeheads

9. Objective Berlin

10. The Kamarilla and the General Staff

11. Preparing the Coup de Grâce

12. Waiting for the Onslaught

13. Americans on the Elbe

14. Eve of Battle

15. Zhukov on the Reitwein Spur

16. Seelow and the Spree

17. The Führer’s Last Birthday

18. The Flight of the Golden Pheasants

19. The Bombarded City

20. False Hopes

21. Fighting in the City

22. Figthing in the Forest

23. The Betrayal of the Will

24. Führerdämmerung

25. Reich Chancellery and Reichstag

26. The End of the Battle

27. Vae Victis!

28. The Man on the White Horse

References

Source Notes

Select Bibliography

Index

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In