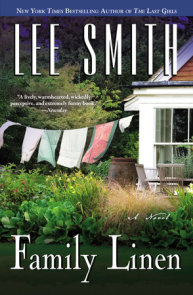

Author Q&A

A conversation between Lee Smith and author Jill McCorkle.

JILL McCORKLE: Fair and Tender Ladies is the finest example of the epistolary novel in recent fiction–a form you also chose for sections of Oral History and more recently The Christmas Letters. By following the chronology of these letters we observe your wonderful heroine, Ivy Rowe, as she moves from childhood to old age. The result is a richly painted portrait of a woman’s entire life as well as an amazing showcase for your wide range and skillful mastering of voice. Did you know from the beginning that this novel would cover an entire life? And what do you think this form offers to the reader that a standard first person narrative would not?

LEE SMITH: Actually, my choice to write Fair and Tender Ladies as an epistolary novel had more to do with a real-life incident than with a conscious literary choice. I had long wanted to write a novel that would honor the heroic lives of the older mountain women I have known—strong, vital women who lived life to the fullest despite their limitations of poverty, lack of education, and lots of children. I wanted to write a novel that would cover the entire life of such a heroine, to show the choices and the people that shaped her. I had already named her: Ivy Rowe. But—as you know very well, Jill—how to handle the passage of time is one of the biggest problems in writing fiction, and I proposed to cover a lot of time, yet I didn’t want to write a tremendously long book either… I was stymied. For the longest time, I couldn’t figure it out.

Then I happened to go to a yard sale in Greensboro, where two frizzy-haired blonde sisters (one big, one skinny) were selling everything their mother had owned. Apparently she had just died. They had emptied the house—everything was in the front yard. They were selling all the stuff you would expect–dime store china, lamps, doilies, Tupperware, kitchen items, clothes—but for some lucky reason, my eyes fell upon a cardboard box hardly visible underneath an old oak table. It was filled with bundles of paper, tied up with ribbons, little pastel grosgrain and satin ribbons, like you might see on a little girl’s pigtails. I leaned over and picked up one of these bundles and untied it. (“Curiosity will be the death of you,” my mother used to say.) Nobody was paying any attention to me; the sisters were bargaining with other browsers. To my surprise the bundle contained handwritten letters, all of which began “Dear June,” and spanned years. I remember the line, “It has been a full year since Jack passed to his reward, and yet I can’t get him out of my mind.” Oh Lord, I thought. I read on. Eventually I hauled the box up onto the table and opened more of the bundles. Each contained letters to June, from many different correspondents. Apparently June had saved just about every letter she’d ever gotten.

“Listen,” I said to the sisters, full of excitement. “This whole box is full of your mother’s letters—I’ll bet you didn’t even know that, did you? See, she’s separated them into bundles, depending on who they’re from, and tied them all up in bows. What a treasure! I know you’ll want to read them, won’t you?”

The sisters look at each other.

“I don’t reckon,” the skinny one said. “Looks like trash to me.”

I couldn’t believe it. “But see what good care she took of them—why, I’ll bet they cover most of her life, too. Look how many there are.”

“So?” the heavyset sister lit a cigarette.

“You mean you do intend to sell them?”

“Well, what would we ever want with them?” the skinny one asked.

I was horrified. “I’ll buy them, then!” I announced. “What’ll you take for them?”

Both sisters looked at me like I was crazy.

“Five bucks?” the big one ventured.

“I’ll give you $3.50!” I am no stranger to yard sales.

“Done!” she slapped the table.

I grabbed up the box and staggered out to my car with it—it was surprisingly heavy. I drove straight home and started reading the letters, canceling my other plans for the afternoon. It was fascinating. After an hour or so, I felt I really knew this woman–June–intimately, just through the letters that had been written to her. I knew her and her husband and her children and her sisters and her neighbors. It was amazing how people who were merely alluded to from time to time, over the years, took on a real living presence. Not that these letters were in any way literary, mind you—they weren’t. But they were real, and all these people seemed real, too, so real that by suppertime they were walking around in my mind, as sympathetic and contrary and nice and mean and baffling as any people in the world.

Halfway, through the box, I knew I would finally write the story of Ivy Rowe—or rather, she would write it herself, as letters. That way, I could zero in on episodes that epitomized whole periods in her life, and I could skip years at a time if I chose.

This solution was so simple, so obvious, that I couldn’t believe I hadn’t been able to come up with it on my own. After all, I had always loved collections of real letters, the correspondence between real people, as well as epistolary fiction and also novels purporting to be written as diary or journal entries—a staple of nineteenth century fiction. My favorite books include The Color Purple, by Alice Walker; A Women of Independent Means, by Elizabeth Forsythe Hailey; Miss Lonelyhearts, by Nathaniel Wert; and Flowers for Algernon, by Daniel Keyes. Somehow I have always felt that as a reader I am more fully drawn into the world of the epistolary novel; there is enough space between the letters or entries for my imagination to really flourish. So, for me, this form offers the reader a chance to participate more in the fiction than is possible with a standard first-person narrative.

I don’t know why it took a yard sale to make me realize something I already knew—but writing is often a product of serendipity. Things just come to you when you need them. As in life, timing is everything. (And I got a really great orange Bakelite bracelet at that yard sale, too….)

JM: You are a writer who is often described as “a woman writer” and / or a “Southern writer”. I would add to that (as Fair and Tender Ladies proves) that you are the voice of the Appalachians, particularly those generations of the past. Clearly your work is not so easily pigeonholed as you have an extremely broad reach and readership. How do you respond to various categories and how do you see yourself placed in literature?

LS: I am always so compelled by whatever story I’m in the process of writing that these other, larger considerations (what people might think of it, what critics will say, how I might be pigeonholed as a writer) are immaterial to me. When I’m writing, all I think about is the story. The story consumes me. I write what I have to write, I guess. I don’t ever envision a reader—-or care if I have a reader or not! My job is just to write it, to be as true to the story as I can. Period. After that, I figure it’s none of my business. People can think or say what they will. If they classify me as a “Southern writer” or as a “woman writer,” then that’s fine with me. I am proud to be both, and I don’t consider those to be derogatory terms.

“Appalachian writer” would be more accurate than “Southern writer,” though. I remember back in college when I first took a course in “Southern Literature,” and we were reading William Faulkner. Well, I loved William Faulkner, but I didn’t identify with those books in any way. They might as well have been set in Russia, as far as I was concerned! Faulkner’s South was not my South. I grew up in the mountains of far southwest Virginia where there were no magnolias or plantations or black people or aristocracy or even money…. nobody lost anything much in the Civil War because we had nothing to lose in the first place. Some men fought for the Union and some fought for the Confederacy, but many of them just didn’t participate. The only white columns in the county were on the Presbyterian Church, up the road from my house.

So I didn’t grow up with that Faulknerian, Deep South sense of loss and racial quilt.

The things that the Appalachian South—and I, as a writer—do share with the Deep South are: a strong sense of place, though my mountains are certainly different from those cotton fields; the importance of religion, family, and the past; and an important tradition of story telling. Nobody in my family read much, but they were all world-class talkers, men and women alike. They could make a story out of anything—a little trip to the drugstore, or three birds lighting on a telephone wire…. just anything. They would talk you to death—and almost did, frankly! I grew up in such a big, close extended family that everybody seemed to know what I was up to, all the time. I couldn’t wait to get away. But then it wasn’t long before I came to understand that those stories I had heard so long ago had really determined the kind of writer I would be: the speakerly kind, rather than the writerly kind. Voice is most important to me. My stories always tell themselves to me in a human voice—often, with a mountain accent. If I can hear the voice, I can write the book. Ivy’s voice was so strong, in fact, that it wasn’t even like writing fiction—it was like taking dictation.

Anyway, I don’t care a bit if people categorize me: it’s fair! I just hope they will read my books.

But I have to say that although you are very kind to call me the “voice of the Appalachians,” I’m not—we have had many great Appalachian writers, though the early ones were not as widely read as they should have been, it seems to me. Two of my favorite novels were Harriet Arnow’s The Dollmaker and James Still’s River of Earth, both immensely inspirational for me. Recently, a lot of good Appalachian fiction has been coming out: books by Bobbie Ann Mason, Silas House, Ron Rash, Charles Frazier, Robert Morgan, Adriana Trigiani, Barbara Kingsolver, Sharyn McCrumb, and Fred Chappell, for instance. Some of these books have reached a tremendous audience; Frazier’s Cold Mountain and Kingsolver’s Prodigal Summer were huge bestsellers. I don’t know whether more of us are writing fiction these days, or whether (as I suspect) publishers are more willing to publish Appalachian fiction since our current national trend toward multiculturalism has made it “in” to have an ethnic or regional identification.

As for seeing myself “placed in literature,” well, I just can’t think about it! I have a suspicion that if you think about it too much—if you become self-conscious about writing—then you really won’t be able to do it any more. It’s like one day when I was swimming laps at the pool, something I’ve done for years, and all of a sudden I started thinking about my breathing and then I suddenly couldn’t breathe any longer. I started swallowing water like crazy.

JM: Your sense of humor is without equal. Can you talk a little about the origin and effect?

LS: I have always been a person who takes a dark view, I guess. I was an often sickly, very emotional, and profoundly weird little child who read all the time, loved ghost stories, and asked unanswerable questions in Sunday School. There were a lot of older people in my family, so there was a lot of illness and death. Both my parents suffered from depression, and were hospitalized from time to time. There is a sense of fatalism in every coal-mining town, anyway. You grow up with it. So a good sense of humor is vital to survival, really. You learn early on that you can either sit in a dark closet or you can make a joke, tell a funny story. Plus, I think a sense of humor is learned, to some degree, and we had some very funny people in our family as well as in town. They loved a good story—the telling of it as much as the punchline. We all did.

JM: I have heard you talk about your very first stories–a house fire, a music box playing “Silent Night” in the ashes–Jane Russell and Adlei Stevenson heading west—to name two. You also have a wonderful story, “Artist” that describes a child’s realization of the world around her much like Welty describes in “One Writer’s Beginning.” Could you talk a little about your first realization that you were a writer?

LS: As I mentioned before, I was a dreamy, imaginative only child who lived to read….and I couldn’t stand for my favorite books to ever end. So I’d write more chapters onto the ends of them—or even sequels! Some of my favorites were The Secret Garden, Heidi, Johnny Tremain, the Nancy Drew books, Jane Eyre…. I’m really a reader first, a writer second. So I was always reading and writing, even as a little girl. I liked to draw, too.

I believe I was also influenced by the fact that Marguerite Henry had stayed at my grandmother’s boardinghouse on Chincoteague Island while she was writing Misty of Chincoteague, one of my all-time favorite books ever. In fact, I loved all horse books. So when we’d go to Chincoteague to visit in the summertime, I’d swing in the wicker porch swing and think, “A real writer sat here—and not only that, a real horse writer!” I was inspired.

JM: You have depicted women in all stages of life and of all persuasions from the most passive victim (as in Black Mountain Breakdown) to those who are strong and ambitious (The Devil’s Dream as well as many others). Where did the idea for Ivy originate and what–when all is said and done–does her life represent in the grand scheme of womanhood?

LS: I’ve already talked a little bit about where the idea of Ivy originated—-in the example of the mountain women I grew up among. I had long wanted to celebrate these lives. But the idea of making Ivy a writer got a real focus when I first met Lou Crabtree in an Appalachian writing class—a community workshop—I was teaching in Abingdon, Virginia. This was back in 1980, I believe. We were meeting, appropriately enough, in the upper room of the Methodist Church. I got hotter and hotter each step I took up the long staircase on my first day of class. Finally I made it, and surveyed the group around the big oak table. It was about what you’d expect—eight or ten people, mostly English teachers, some retirees. We had already gone around the table and introduced ourselves when here came this old woman in a man’s hat and bedroom shoes, grey head shaking a little with palsy, huffing and puffing, dropping notebooks and pencils all over the place, greeting everybody with a smile and a joke. She knew them all. She was a real commotion all by herself.

“Hello there, young lady,” she said to me. “My name is Lou Crabtree, and I just love to write!” My heart sank like a stone. This is every creative writing teacher’s nightmare: the nutty old lady who will invariably write sentimental drivel and monopolize the class as well.

“Pleased to meet you,” I lied. The week stretched out before me, hot and intolerable, an eternity. But I had to pull myself together. Looking around at all those sweaty, expectant faces, I began, “Okay, now I know you’ve brought a story with you to share with the group, so let’s start out by thinking about beginnings, about how we begin a story. Let’s go around the room, and I want you to read the first line of your story aloud.”

So we began. Nice lines, nice people. A bee hummed at the open window; a square of sunlight fell on the old oak table; somebody somewhere was mowing grass. We got to Lou, who cleared her throat and read, “Old Rellar had thirteen miscarriages and she named every one of them.”

I took a deep breath. The hair on my arms stood up. “Keep going,” I said.

She read the whole thing. It ended with the lines: “You live all your life and work things up to come to nothing. The bull calf bawled somewhere.”

I had never heard anything like it.

“Lou,” I asked her after class, “have you written anything else? I’d like to see it.”

The next day, she brought a suitcase. And there it all was, poems and stories written on every conceivable kind of notebook and paper, even old posters and shirtbacks.

Lou grinned at me. “This ain’t all, either,” she said.

It wasn’t.

Lou Crabtree had been writing for 50 or 60 years, on anything she could get her hands on, “just to give me pleasure in my soul,” with no thought of publication. Writing was how she lived; it was what she lived by. She’s nearing 100 now, and it’s still what she lives by. For the first time, that hot afternoon, I understood the therapeutic power of language, the importance of the writing process itself. Certainly, Lou served as a real inspiration for my character Ivy, who writes letters to make sense of her life, in much the same way Lou wrote her stories and poems.

If anybody is interested in reading her work—and I hope you are!—her book Stories from Sweet Holler was published by Louisiana State University Press, and her collection of poems is available from The Sow’s Ear Press, 19535 Pleasant View Drive, Abingdon, VA 24211-6827. She can still be found sitting on her front porch in downtown Abingdon, and she is still an inspiration—a role-model—for me.

And just as Lou is a real artist, Ivy is a real artist, though hers was not a public kind of art. Her letters went mostly to her family, but they were her way of making sense of her life. Art is ordering, really. Making a shape out of the chaos of real life. And as Ivy said, it was the writing itself that signified, not the letters. This is true for the cook who makes the beautiful cake that will be all eaten up….the woman who knits the sweater which will be handed down from child to child and soon worn out…the lady who loves to set the table….the grandmother’s piecing the quilt. Much of women’s art is all about the doing, not the product. So I see Ivy as a passionate woman artist, a real artist, in a way that she herself didn’t understand.

JM: Since the first publication of this novel, you have been actively involved in oral history projects. Could you speak a bit about your work and how it connects to the life of Ivy Rowe? Did one feed the other? Also, Fair and Tender Ladies is filled with folklore and details of Appalachian life. Do you research?

LS: Though I grew up in the Appalachian mountains, where Fair and Tender Ladies and my other mountain novels are set, I still do a lot of research for each one. I need to get my mind into a certain place, as much as I need to know details such as how they made soap, for instance. Besides, I love to read old histories and diaries; and I’ve been taping my relatives and others for years and years. Oral history is one of my favorite pastimes. I guess it just “gives me pleasure in my soul,” as Lou said. The old dialect—the cadence, the turn of phrase—seems particularly poetic to me. I love the way it sounds, the same way I love old time music—the ballads, or bluegrass. It lifts me up to another place, you might say. My work is very closely linked to music and to speech, so research—especially oral history—“gets me going” in a way nothing else does.