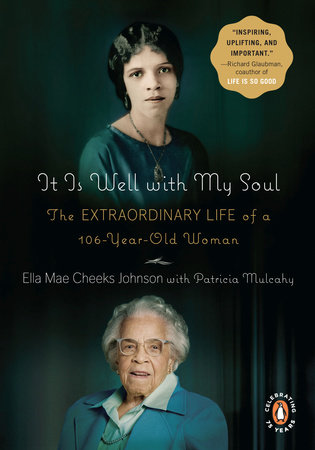

It Is Well with My Soul Reader’s Guide

By Ella Mae Cheeks Johnson Patricia Mulcahy

INTRODUCTION

On January 20, 2009, Ella Mae Cheeks Johnson woke up “before dawn and put on [her] pearls and layers of clothes” (p. 164) before making her way to the National Mall in Washington, D.C. There the 105-year-old woman waited for eight hours—in a frigid cold that discouraged others just a fraction of her age—so that she could witness Barack Obama’s inauguration as President of the United States. As incredible as her stamina and determination were that day, her attendance simply marked one more chapter in a life that was never less than inspirational.

Born Ella Mae Dawson in 1904, at a time when “black citizens had no official papers” (p. 4), she never met her birth father, and her young mother died when she was four. Her mother’s parents were too poor to raise the orphaned girl, so their next-door neighbors, Moody and Tennie Davis, took her in and “embraced her as their own” (p. 6). She led a modest childhood, but absorbed the Davises’ values of hard work and compassionate giving that would guide the rest of her life.

Growing up in the Jim Crow South, Ella Mae lived in a segregated world. She recalled that “because of limited funds and prejudice, public facilities were denied me, including public transportation, swimming pools, restaurants, and most hurtfully, libraries” (p. 13). Yet, despite these obstacles, Ella Mae graduated from high school as salutatorian and gained admission to Fisk University, a historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee.

After earning her master’s degree from Case Western University, she went on to become a social worker, formalizing her lifelong commitment to helping those in need. When her beloved husband Elmer died, she raised two sons on her own. Fifty-four years after her retirement, Ella Mae said, “I wake up and often I look at the painting of the Good Samaritan. In terms of what I’ve done lately, I think: Was that compassionate? Did that help anybody? Could I do something different?” (p. 145).

Although Ella Mae’s religious faith was profound, she never felt the need to impose her own beliefs on others. Late in life, she began to travel the world, and took many trips to the Holy Land. “For me,” she reflected, “there is nothing more important than a broad vision of the world. . . . I was as comfortable praying in Jewish synagogues and the Bahai shrine in Haira as in a Japanese shrine outside Tokyo” (p. 126).

Ella Mae died in March 2010. For the last thirty-four years of her life, the twice-widowed great-grandmother lived in a retirement community in Cleveland. She was an avid reader. A self-dubbed “beggar for needy people” (p. 153), she raised thousands of dollars for HIV/AIDS relief and to help children born with cleft palates.

It Is Well with My Soul is the uplifting story of one woman whose outwardly ordinary life encompassed the great complexity of the last American century.

ABOUT ELLA MAE CHEEKS JOHNSON

Ella Mae Cheeks Johnson (1904–2010) was born in Dallas, Texas, and lived much of her life in Cleveland, Ohio.

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In