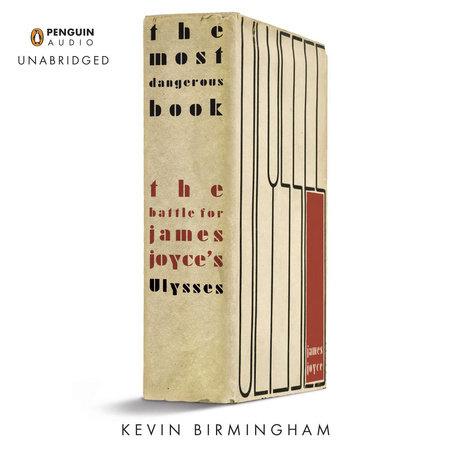

The Most Dangerous Book

By Kevin Birmingham

By Kevin Birmingham

By Kevin Birmingham

By Kevin Birmingham

By Kevin Birmingham

Read by John Keating

By Kevin Birmingham

Read by John Keating

Category: Arts & Entertainment Biographies & Memoirs | Literary Figure Biographies & Memoirs | Literary Criticism

Category: Arts & Entertainment Biographies & Memoirs | Literary Figure Biographies & Memoirs | Literary Criticism

Category: Arts & Entertainment Biographies & Memoirs | Literary Figure Biographies & Memoirs | Literary Criticism | Audiobooks

-

$19.00

May 26, 2015 | ISBN 9780143127543

-

Jun 12, 2014 | ISBN 9781101585641

-

Jun 12, 2014 | ISBN 9781101564318

862 Minutes

Buy the Audiobook Download:

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

The New Male Sexuality

Men in the Off Hours

Selected Poems of Vladimir Nabokov

In Search of Lost Time Volume II Within a Budding Grove

Mandela’s Way

31 Days Toward Passionate Faith

The Diaries of Franz Kafka, 1910-1923

Paris versus New York

The Beggar, The Thief and the Dogs, Autumn Quail

Praise

Dwight Garner, The New York Times:

“Kevin Birmingham’s new book about the long censorship fight over James Joyce’s Ulysses braids eight or nine good stories into one mighty strand… The best story that’s told… may be that of the arrival of a significant young nonfiction writer. Mr. Birmingham, a lecturer in history and literature at Harvard, appears fully formed in this, his first book. The historian and the writer in him are utterly in sync. He marches through this material with authority and grace, an instinct for detail and smacking quotation and a fair amount of wit. It’s a measured yet bravura performance.”

Michael Dirda, The Washington Post:

“Birmingham has produced an excellent work of consolidation…. [A] lively history …. The Most Dangerous Book is impressively

researched and especially useful for its meticulous accounts of various legal battles. It is meant to be fun to read and, setting aside my fogeyish cavils, it is.”

The Economist:

“[G]ripping. Like the novel which it takes as its subject, it deserves to be read.”

The New Yorker:

“Terrific…. The Most Dangerous Book is the fullest account anybody has made of the publication history of Ulysses. Birmingham’s brilliant study makes you realize how important owning this book, the physical book, has always been to people.”

Vanity Fair:

“Birmingham recounts this story with a richness of detail and dramatic verve unexpected of literary history, making one almost nostalgic for the bad old days, when a book could be still be dangerous.”

The Wall Street Journal:

“The story of Ulysses has been told before, but not with Mr. Birmingham’s thoroughness. The Most Dangerous Book makes use of newspaper reports, court documents, letters and the existing Joyce biographies. It looks back to a time ‘when novelists tested the limits of the law and when novels were dangerous enough to be burned’ and makes one almost nostalgic for it.”

Dallas Morning News:

“Hundreds of books and thousands of articles have been written about Ulysses since its publication. Kevin Birmingham’s The Most Dangerous Book is a splendid addition…. this book has groundbreaking new archival research, and it thrills like a courtroom drama.”

Boston Globe:

“I am not a Joycean. But I loved Kevin Birmingham’s The Most Dangerous Book anyway. You don’t need to be a Bloomsday devotee to enjoy or profit mightily from it. Birmingham… writes with fluidity and a surprising eye for fun. He probably has read through the mountains of books and scholarly articles on Ulysses and seems obsessed with the book itself, but wears it all lightly. [A] vivid narrative [that]…makes you want to go back and read—and treasure—Joyce’s novel because he liberally salts the novel’s backstory with memorable anecdotes and apercus, especially at the close of each chapter.”

Houston Chronicle:

“Lively and engrossing.”

Slate:

“[A] deeply fun work of scholarship that rescues Ulysses from the superlatives and academic battles that shroud its fundamental unruliness and humanity.”

Salon:

“Astute and gorgeously written…. [The] battle for Ulysses…is a story that, as Birmingham puts it, forced the world to ‘recognize that beauty is deeper than pleasure and that art is larger than beauty.’ He has done it justice.”

Chronicle of Higher Education:

“An essential, thoroughly researched addition to Joyceana and a consistently engaging narrative of how sexuality, aesthetics, morality, and jurisprudence collided almost a century ago.”

The Nation:

“Kevin Birmingham’s The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce’s Ulysses casts its nets… widely, synthesizing enormous amounts of information and describing in detail the multiple circumstances surrounding the gestation, publication and suppression of Ulysses. Birmingham is a fluid writer, and the more intricate the detail, the more compelling the narrative he constructs: his account of the rise of American obscenity laws… is as gripping to read as his account of the barbaric eye surgeries Joyce endured or his account of the nearly slapstick manner in which Samuel Roth published a pirated edition of Ulysses in 1929.”

Publishers Weekly (starred):

“Exultant….Drawing upon extensive research, Birmingham skillfully converts the dust of the archive into vivid narrative, steeping readers in the culture, law, and art of a world forced to contend with a masterpiece.”

Kirkus Reviews (starred):

“[A] sharp, well-written debut….Birmingham makes palpable the courage and commitment of the rebels who championed Joyce, but he grants the censors their points of view as well in this absorbing chronicle of a tumultuous time. Superb cultural history, pulling together many strands of literary, judicial and societal developments into a smoothly woven narrative fabric.”

Library Journal:

“What begins as simply the ‘biography of a book’ morphs into an absorbing, deeply researched, and accessible guide to the history of modern thought in the first two decades of the 20th century through the lens of Joyce’s innovative fiction.”

Booklist:

“Birmingham delivers for the first time a complete account of the legal war waged…to get Joyce’s masterpiece past British and American obscenity laws. Birmingham has chronicled an epoch-making triumph for literature.”

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In