Author Q&A

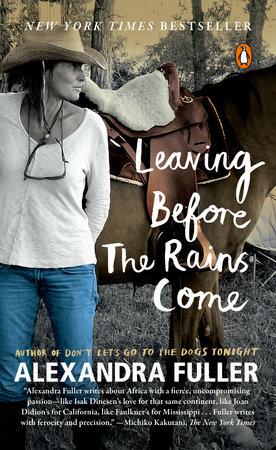

An Interview with Alexandra Fuller:

1. Leaving Before the Rains Come is a frank examination of your marriage and its dissolution. Was it more difficult to write than your previous books?

Yes, writing this was much more difficult than my other books, partly because I am represented in these pages as a free and adult agent (in as much as any of us are “free”). In my other books, I am either a child, which is a great place to write from, since one can observe without judgment, or I am more of a bystander which gives the writer the breathing room of a little space. In this work, I am fully engaged in the action as a grown woman, with children of her own, and if there was ever a lighting rod it’s that combination. Women are expected to sublimate huge parts of their experience, for the sake of their children, or for some other moral cause (wifely virtue perhaps). Writing frankly about marriage is still pretty taboo for those reasons.

Of course, that being said, I wanted to protect my children and my former husband from undue anguish without at the same time subjecting myself to censorship, which is its own kind of undue anguish. It was tricky. How should I use what I learned in a long and uneasy marriage for the purposes of the book and not exploit the privilege of twenty years of unparalleled intimacy with my ex-husband? How can I write about the loneliness of that marriage without implying that my children were somehow part of that loneliness? They were not. Not at all, but they are also necessarily a very small part of this book because it was so important that I protect their privacy.

Now, all of that being said, I realize I am often accused of being “brutally honest” in my work. I find this shocking because my internal experience is that I am holding back an awful lot. My conclusion is that most people are suppressing a lot, and lying often!

Does writing about my life and my realizations make me selfish and a bad mother/wife, or does it make me as wholly realized as I can be in this moment? I think women especially are expected to remain silent, martyred, and grateful. Grateful that any man would want to marry them, grateful for the not always rewarding slog of domestic drudgery, grateful for children. But I believe that those of us lucky to have the protected right to free speech have to speak out. Marriage, motherhood, and self-realization often conflict with one another. It’s the messy, human, wonderful hand women have been dealt.

Although I want to add here that I am aware that marriage is not just the experience of women, or of heterosexual couples. My hope is that with a more inclusive definition of marriage, the culture of marriage will itself become more flexible and less oppressive not only to women, but also to men, lesbians, gays, transgender folk, and for the children they love and raise together. I think a lot of the terror around marriage equality has had to do with a fear of this increased flexibility and openness. Traditional marriage has customarily served the patriarchy rather well, while oppressing women and excluding sexual minorities. What will it look like as we expand our definition of family, question the roles of “mother” and “father” with a more open mind, and allow our children to be raised with possibility rather than prohibition?

2. You and Charlie finally divorced, but not until after having three children and spending almost two decades together. Does the title of your book imply that you left before things became impossible or that you ignored the warning signs and suffered the consequences?

No, the title refers to the restlessness of migrating animals, the stirring before the rains that forces them to leave when it makes least objective sense. It’s not that things are going to get worse—after all the animals are leaving at the driest time of year, things can’t get any worse—but that things simply have to change. The animals are following some deep instinct—far deeper than mere understanding—that their survival depends on leaving. I think humans have that instinct too, but we numb and deny and equivocate, or we are bullied and terrified and trapped. Leaving a marriage is never easy; it’s brutal for the couple, for their children, and for societies. But staying in a bad marriage is a living death.

The title also refers to something Dad said, speaking as a southern African farmer. He always felt that if you were going to leave a piece of land, there was a season in which to do so, and it had to be before you planted another crop, made more investments, and then had to wait out a whole year for the harvest. Dad often used metaphors of farming when he was really talking about life. You really had to track what he was saying with great care to make sure you didn’t miss his wonderful brand of wisdom.

3. Would you have had the courage to leave Charlie if you hadn’t found success as a writer?

I’ll never know. But I think it would have been much, much harder for me to leave. I was desperately unhappy for much longer than I ever allowed myself to acknowledge partly because I had so few resources to back me up. I had small children, I didn’t have a U.S. passport, my parents certainly weren’t going to welcome me back into their lives, and I didn’t know anyone in the States. I was trapped and in a way it was a terrible recipe for a happy marriage because my weakness became a weakness in the relationship. If people stay together because their circumstances require it of them, the marriage becomes a prison, not a place of comfort, growth, and support. If people stay together because there are choices, and options and openness, well then there is at least breath and as long as there is breath, there is a chance that we can evolve and grow.

4. What advice might you give to other women who feel trapped in an unhappy marriage?

I think it’s different for every person (men and women). But if you have tried everything to stay in the relationship, and still can’t breathe, then get out while you still have the strength to regain your life. I can’t imagine making the decision lightly; it’s so incredibly hard. But truly if you are spending most of your time thinking about how unhappy you are, it’s a quiet sort of violence not only to yourself, but also to your partner and to any children you have if you stay put until you are just a body in motion, but not an evolving soul.

I would hate my daughters or son to settle in some relationship in which both parties are slowly losing the oxygen in their tanks—or sucking each other dry—just out of fear, duty, or obligation. It serves no one. Not a single person. Everyone, regardless of his or her merits or demerits, must figure out for him or herself how best to do the work they were put on earth to do. It’s impossible to do one’s work if one can’t breathe, isn’t seen, and feels no support from one’s partner.

5. You meditate quite a bit on Charlie’s invulnerability, even entitling one of the chapters, “Mr. Adventure’s Immunity.” Yet, he eventually does fall victim to a horrific and improbable accident. In its aftermath, did you ever reconsider your plans to divorce him?

Of course I reconsidered my plans to divorce him after his accident, after I left the house, even after the divorce was final. But the terrible accident was absolute proof, if I needed it, that our quiet suffocation of one another was literally going to hurt one or both of us. I didn’t need another awful lesson.

That doesn’t mean it was easy to go through with the divorce. If anything, the accident made it much, much harder. Charlie and I operated well under duress and less well when there was no drama. It took me a long time to realize that this is the definition of trauma-bonding, and the cycle of that is exhausting: Tension, followed by a fight, followed by making up, followed by a period of peace until the next round of tension built up. Had I stayed married to Charlie after his accident, it would have been—on steroids—another go around in the trauma-bonding cycle.

When I see Charlie now, we can be friendly without needing to be friends. In fact, I don’t think either of us would consider each other interesting were we to meet one another now, let alone mates that can spend the rest of their lives in the greatest of intimacy. Unlocked from our repeating cycle of trauma-connect-trauma-connect we can be kinder to each other, and better parents. But we were never really partners. That’s not the fault of one, or the other—we have wildly different worldviews. His reality is not my reality. We literally can be looking at the same scene and walk away with two wildly different interpretations of that scene. It resulted in constant conflict. Now that we are no longer married, we no longer have to waste so much time convincing each other to see things “my way.”

6. How do your children feel about Leaving Before the Rains Come? What advice have you given to them regarding love and marriage?

My children don’t really want to talk about the book. But we certainly talk about relationships and love and the divorce and marriage. We have, I think, healthy and open conversations. It’s certainly not always easy. The divorce was hugely painful for all of them, and it was an incredibly difficult, scary time for them too. I think that is the hardest role as a mother: How do you protect your children adequately, while at the same time ensuring that you have enough oxygen in your own system? And how do you protect them from the things that should remain private in all marriages while sharing your experiences with them so they are aware that marriage isn’t the rosy world promised by the media?

I tell my children that just for a start, in order to have successful relationships, they have to learn to speak honestly about their needs. In other words, they need to be able to say, “I feel hurt,” “I feel lost,” “I feel overwhelmed.” So often, I think we end up being inadvertently manipulative and dishonest because we don’t use words effectively. We’re embarrassed by our feelings or we’re unable to admit emotional vulnerabilities so they come out sideways as diseases, allergies, depression, addictions and they escalate and escalate until we literally end up on a stretcher. Most pain can be averted if we have the courage early on to say, “I’m sad.” And if a parent, a lover, a spouse, a best friend can hear that small voice, then there’s a chance for a relationship. If that small voice is ignored, then I think we set ourselves up for a lifetime of hurt and opposition with both sides feeling increasingly wounded.

I feel strongly that our violent culture is fed out of a great denial of love. Now I realize that sounds a bit basic and probably out of date, but love is the most difficult challenge that has ever been set to humanity. We have great examples of love’s prophets—Christ, Buddha, Mohamed, Rumi (there are fewer women examples because historically women’s wisdom has been hidden)—and yet we return over and over again to fear, bullying, terror, and selfishness as if these are the answers.

No, no, no love is the answer. But it’s very brave and difficult to interrupt the path of violence and greed to serve the greater good. Ultimately though, what else are we on the planet to do? Use more of it up? That’s killing us all. Pave more of it over? Pour more blood into its soils and pollution into its rivers? No, we are here to pay attention to our souls and to the souls of others, and to love one another.

One of the books I loved reading to my children was Wolf Elbruch’s The Big Question. And the big question is, “Why are we here?” The end of the book leaves pages for the reader to answer that question. It’s a simple, genius, timeless text for little people, and for older people who need a reminder. It’s a wonderful question with which to start each day, and as far as I can tell, my answer never changes. In a word, “love.” And, as I remind my children, love is made up of acts, not feelings.

7. Do you ever consider returning permanently to Africa? Or living anywhere other than Wyoming?

I have dreamed of returning to Zambia, but my children are here, and Wyoming has become a sanctuary to me. I love the mountains, the intimacy of winter, the extremes of weather and landscape. It is also a landscape I watch carefully for the abuses heaped upon it in the name of economic development, mostly in the form of hydro-fracking. You can’t love a place without wanting to protect it. And once you have signed on for that task, well then, walking away is a kind of capitulation. I shall always carry huge shards of Zambia and Zimbabwe with me, and the farms of my youth—my parents’ current farm—I love these places, but they are no longer home to me.

8. At what point did you realize that while you would never be American, you were also no longer quite African?

In 2008 when I was writing about a young cowboy killed on Wyoming’s oil patch. I fell in love with Wyoming in all its harsh, uncompromising beauty. And I knew I needed to belong wherever I was, not wherever my passport or skin-color or accent decreed.

9. After a relationship as challenging as yours and Charlie’s, can you imagine marrying again?

Yes, of course. I didn’t stop loving Charlie just because I couldn’t stay married to him. I love the idea of marriage. I think it provides security, sanctity, and, ideally, space. If marriage is suffocation, then it’s not working. If it’s those other things, then it is. But it requires both parties to stay conscious, open, caring, vulnerable, and not defensive.

10. Who are some of your favorite writers? Is there a writer you feel best captures life in Africa?

I go back and back to a handful of writers over and over again: Graham Greene is a favorite, as are Marilyn Robinson, V. S. Naipaul, and Michael Ondaatje.

Then there are the books I read and reread: Paul Bowles’s A Sheltering Sky, Mary Robinson’s Why Did I Ever, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Heat and Dust, for example.

As for a writer that “best captures life in Africa,” well, it can’t be done. There are fifty-three countries (give or take), thousands of languages, hundreds of cultures, and such varied experiences and histories.

Out of Liberia I adored Hélène Cooper’s The House at Sugar Beach and Ellen Sirleaf Johnson’s This Child Will be Great. The great grandfather of all African letters out of Nigeria, Chinua Achebe, writes so eloquently about pre-independence and post-independence in his masterpieces, I think they’re eternal, poetic and fierce. Farther south, I found Elizabeth Marshall Thomas’s The Old Way an incredible, and moving insight into the lives of the San in Botswana. Peter Orner’s The Second Coming of Mavula Sekongo was a wonderful look at Namibia. J. M. Coetzee’s The Life and Times of Michael K is a harrowing description of apartheid-era South Africa and Disgrace is a very discomforting examination of post-apartheid South Africa. Binyavanga Wainaina’s memoir, One Day I Will Write About This Place is a terrific, rollicking read and it covers his life in Kenya, his education in South Africa, and his visits to Uganda. There are more and more great writers coming out of Africa all the time, and their works are as varied as the people who write them.

11. Before you wrote Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight, you wrote several novels that were all rejected by publishers. Now that you are a more seasoned storyteller, do you think you might give fiction another try?

Not as long as truth continues to be stranger than anything I could ever make up. Although, I suspect that most novelists would say that their work is “truth.” So maybe . . .