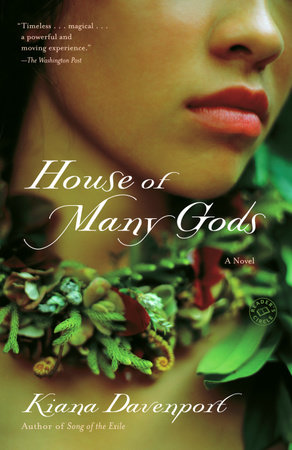

Author Q&A

A Conversation with Kiana Davenport

Ron Fletcher, a Boston Globe correspondent and English teacher at Boston College High School, is working on a novel set in hockey rinks throughout Boston.

Ron Fletcher: House of Many Gods is set in Hawai‘i and Russia, which seem like two disparate cultures. What prompted you to include Russia in this novel?

Kiana Davenport: I knew that one day I was going to write about the U.S. military’s relentless bombing of our sacred M¯akua Valley. And I was further inspired by a man named Rostov Anadyr, a Russian filmmaker I met in Hawai‘i in the 1980s, who was the inspiration for the character Nikolai Volenko. At that time, Rostov was shooting a documentary film about contamination in the Pacific, resulting from decades of nuclear testing and dumping. He hoped to integrate this film with the ecological horrors he had been filming in Russia for years.

RF: In the novel, the character of Nikolai seems almost larger than life: his birth in an ice hut, his boyhood of begging and living in drainpipes, his genius in mathematics, his ambitious and compassionate filmmaking. How closely does he parallel Rostov Anadyr?

KD: Well, the actual man had an amazing life. He was born in a remote village east of the Ural Mountains, where most folks did not know what a zipper was and had never heard a dial tone. His clothes seldom matched, and his shoes had broken, knotted laces. But he was brilliant and funny and generous, and people were drawn to him. In 1987, Rostov returned to Russia to film the aftermath of the Chernobyl meltdown, its harrowing effects on surrounding towns and cities. He was due to return to Hawai‘i to complete his film. We never saw or heard from him again, though I have searched for him in Moscow and St. Petersburg. He may have fallen ill from toxic exposure, or he may have been imprisoned like many political artists are, despite perestroika. He may be dead. I wrote this book in his memory.

RF: In previous interviews you’ve mentioned your cousins who inspired the characters of Rosie and Lopaka, and friends who have glimpsed bits of you in Ana. Though it’s difficult to imagine fiction without the imprint of autobiography, I wonder what sort of relation you see between the two genres in this work.

KD: The main character, Ana, is abandoned by her mother as a child. She grows up a loner and a survivor; she even survives breast cancer. Though I have never had cancer, I felt terribly abandoned as a child when my Hawaiian mother died of cancer at a very early age. You see, in early drafts of the novel, it was the mother, not the daughter, who is diagnosed with cancer. But it was too difficult for me to write: it brought back too many memories of my mother. So I transferred the illness to another character. It’s a writer’s ploy, something to hide behind when things get too personal. It’s also a dilemma, because I don’t think there is such a thing as pure fiction. Every word we write is freighted with our thoughts, our history, our DNA.

RF: Though much of contemporary American fiction often seems stuck in a solipsistic or apolitical mode, your novels embrace whole generations of families struggling to survive, while also addressing urgent topical issues like environmental degradation, poverty, and racism. How do you reconcile the two? Do you feel obligated to address social and political injustices?

KD: No, I don’t. My only obligation is to write novels with as much grace and wit and imagination as possible. I do seem to write about family, caught in the prevailing winds of their particular time. And in that sense I often touch on politics. But what is uppermost in my mind when I begin a novel is fragility, the human condition, and how to discover the heroic in a character. I think every writer prays that he or she is touched with a cosmic ache of specialness–that our books will endure. Writing about politics does not bring that kind of immortality.

RF: How do you reconcile that view with the sections in your novel about the bombing of M¯akua Valley by the U.S. military?

KD: I think there must be some moral code a writer holds to, a time when he or she stands up and says, “Enough.” M¯akua exists. It is a sacred place: a pristine valley of thousands of acres where our ancients came to worship at heiaus, or temples, and where they kept the bones of their ancestors carefully preserved in caves. The waters offshore were immaculate. Whales came to birth their calves; schools of porpoises gathered in the thousands. During World War II the U.S. military leased it from our government for “war maneuvers.” They’ve continued nonstop since then, bombing everything in the valley. It’s now a cratered moonscape, with nothing left alive. The waters offshore are polluted from exploded ordnance. For decades, Hawaiians have marched and legislated against the bombings. Finally, in the late 1990s, the United Nations stepped in. The military was forced to halt while environmental impact studies were conducted. But after 9/11, military “war maneuvers” were drastically increased again–on several of our islands. Our soil and waters are full of toxins and radioactive fallout. Our people are ill with respiratory diseases, cancer, leukemia. Perhaps this novel was my way of saying “Enough.”

RF: Both Ana and Niki endure their share of suffering: illness, deprivation, the death of loved ones. Yet each is defined, in fact, strengthened, by these tragedies. To what extent does suffering shape one’s character? Is it the sine qua non of our being?

KD: There are several answers to that question. During my research in Russia, I interviewed two unforgettable men, Boris Ozhogin in Moscow and Rudolph Otradnov in St. Petersburg. In late-night conversations over vodka, each man talked about his years spent in the gulags, the Russian slave labor camps in the 1950s. Describing that bestial existence, Boris felt he had been stripped of his humanity, that part of him was dead forever. “Who would want to kill a friend for a piece of bread?” he said. “Who can recover from such an act?” Rudolph was the opposite. He was one of those expansive Russians who seem to embody all the drama and chaos of his country. “But one must suffer,” he shouted, pounding his chest. “It is what made me so human! Now I love life. I cherish every moment, every detail!” It’s accepted that suffering is part of our human experience. How it shapes us depends on the individual. It’s that old adage, “That which does not kill you, strengthens you.” I think Niki is such a larger than life character specifically because of how he has suffered. It has given him his humanity.

RF: The spirit of optimism and perseverance embodied by Niki seems to describe the novel’s conclusion as well. It will strike some as a surprising note on which to end, given the novel’s tragic elements. How did you arrive at this hopeful ending?

KD: Originally the book had a very bleak ending. It was rational and logical, I thought. But unlike a lot of modern writers, I am not a cool, detached and rational author. I believe in passion, deep passion, in life and in writing. People who dismiss all real emotion as sentimentality are cowards. So, after about twenty drafts, I realized that this couple, Ana and Nikolai, had suffered enough. Both orphans in a way, they had overcome amazing odds, they had achieved important things. I felt that these two people, whom I loved, had earned their right to be happy. I finally realized that the bleak, logical ending would have been entirely false. There’s a quotation from Dostoyevsky that stayed with me throughout the writing of this novel. He said, “One must love life before loving its meaning, for when love of life disappears, no meaning can console us.” It’s what I wanted to convey at the end of the novel, that this couple, though still struggling to survive, absolutely loves life, that living is indeed “a sacred act.”

RF: Placed alongside your first novel, Shark Dialogues, and your last novel, Song of the Exile, House of Many Gods seems to complete an arc of Hawaiian history, a centuries-long chronicle that some reviewers have described as your “Native Hawaiian trilogy.” Was this done by design, discovery, or a bit of each?

KD: Though I sensed I was coming to the end of something when completing House of Many Gods, it was only in retrospect that I saw what you refer to as the arc of Hawaiian history, beginning with our last monarch and ending near the present. Of course, there are still thousands of stories to tell.

RF: Which one of those thousands will you choose next?

KD: Well, for the first time I am delving into the haole–or Caucasian– side of my heritage. My father, Braxton Bragg Davenport, was a U.S. sailor from Talladega, Alabama. His ancestor was a one-armed cavalier who fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War at Shiloh, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga. He fell in love with a part-Asian woman and they ultimately ended up in Hawai‘i.

RF: All paths lead home?

KD: It seems that way. In life, and in fiction, I always come back to my beloved islands.