Author Q&A

Q. How did you decide to write about the Elgin Marbles?

I first saw the Elgin Marbles in 2001 at the British Museum when I went to see an exhibit about Cleopatra. I was researching my novel Kleopatra and I wandered into the Duveen Gallery where the marbles are housed. I listened to the story behind the marbles on the audio guide and had an intuition that it would be good fodder for a novel. When Susan Nagel’s biography of Mary Nisbet, Countess of Elgin came out in 2004, I eagerly read it and was blown away by Mary’s contribution to the acquisition of the treasures, and also by the absence of references to her in the sources. I thought, hmmm, another woman who defied society’s idea of how a woman should behave and paid a steep price for it–and was forgotten. I got very excited about writing about her.

Q. What did your research for Stealing Athena entail?

I am definitely a research freak. I’m the sort of writer who thinks that if she doesn’t know everything, she doesn’t know anything.

Stealing Athena was difficult to write simply because of the enormity of the research. It was crucial for me to understand the Ottoman Empire, the British Empire, Napoleon, the French Revolution, the Golden Age of Pericles, and all the ensuing cultural studies that would have impacted the people in those civilizations and time periods. I have posted a selected bibliography on my website, but it doesn’t begin to encompass all my sources. And of course, I also visit the pertinent locations in all of my novels to do as much onsite research as possible, in addition to soaking in the atmosphere and breathing the air. That’s the really fun part. I like to literally share molecules with my characters.

Q. How long did it take you to research and write Stealing Athena?

As I said, I started thinking about it in 2001, with interest heating up in 2004. Once I get an idea for a book, it’s never far from my mind, even if I am writing something else. Luckily, I studied ancient Greece both in graduate school and on my own for other projects, so I already had a solid base of knowledge for both the Golden Age of Pericles and for his mistress, my other heroine, Aspasia.

Q. You must become engrossed in the period of history and lives of the historical figures given your investment of time, research and writing. Is it difficult for you when you have finished to leave your characters behind?

Oh yes! I have often thought that I should do what other historical novelists do–specialize in only one time period. With my interests sort of sweeping all of history, it’s as if I have to earn a PhD every time I write a book. I put enormous–and I do mean enormous–time and energy into studying these cultures and constructing these characters, and then I have to forsake them for the next! It is indeed quite sad. I suppose that on the bright side, I am fortunate to be able to spend time with so many of history’s most fascinating people. I mean, I feel as if I’ve dated Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, and Pericles, and made good friends with Aspasia, the Este princesses, Socrates, and Leonardo da Vinci. Kleopatra, well, let’s just say that we’re on very close terms.

Q. Do you think that history and fiction compliment each other in the writing process?

I do think that scholarship and fiction work together often in the way that I was inspired by Susan Nagel’s biography. A scholar brings new understanding to something from the past, and the fiction writer or dramatist is inspired to try to popularize it. It’s common knowledge that Shakespeare wrote with a copy of Plutarch open on his desk (so do I!).

Q. The story of Lord Elgin and Mary Nisbet Elgin was rich enough to hold the plot of an historical novel. What made you decide to incorporate Aspasia and her story into Stealing Athena?

I guess I just wanted to make my life a lot harder! I have long held an interest in Aspasia. She was such a rarified creature–a respected philosopher in an era when women were almost unilaterally illiterate and denied even basic civil rights. One day while I was lying on the floor of my office looking at the ceiling, the idea to have Aspasia watch the Parthenon go up and have Mary watch it come down just descended upon me. I suppose that I love the classical Greek world above all time periods and feel very comfortable writing in that space.

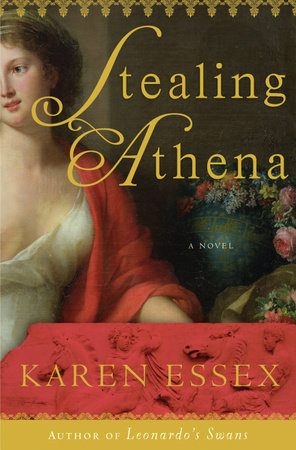

Q. The jacket is so beautiful and splendidly illuminates what the reader will find inside the pages. Did you have a role in the cover art design?

Just as our first impressions of people often prove to be accurate, I do believe that we can frequently judge a book by its cover, which is why I try to be as pro-active as possible in the design of my book covers. I am a very deliberate writer in that I know exactly what story I am trying to tell and what themes I wish to convey to a reader. It’s crucial that a book cover reflect those things, and who would know better than me? With both Leonardo’s Swans and Stealing Athena, I knew which art should grace the covers before I had written the books. My undergraduate work was in theatrical design. I’m a very visual person, and my books are often inspired by works of art. The cover is the "face" of the book, if you will. A reader may not judge the book by its cover, but the reader cannot get inside the book without seeing and regarding the cover. Like faces, a cover is either alluring–or not.

Q. Can you tell me more about the painting and other elements on the jacket?

The painting on the cover of Stealing Athena is a self-portrait by the French painter Marie-Geneviève Bouliard in which she envisioned herself as Aspasia. I selected it because it is an imagined portrait of one of my two heroines done by a female artist who was painting in the time period of my other heroine, Mary Nisbet (circa 1794). Considering the dual narratives of my book, you can’t get more perfect than that! The insertion of a small portion of the Parthenon frieze at the bottom was genius, as far as I am concerned. And I also love the gilded Turkish trim that the designer uses at the top of the cover because it brings in another element of the book, which is its setting in Ottoman-ruled Turkey and Greece. I think the result is stunning. I think it’s amazing that we were able to convey so many elements of the book in the cover design with visual clues alone.

Q. Is there a continuing theme for your novels?

My novels are about women and power. Throughout every historical era, dynamic women have influenced world events but history has rarely recorded their accomplishments. In fact, when my daughter was in grade school, she and her friends could not name any powerful women except…Madonna! Whether you are the mother or the father of a young girl, I’m sure that you find that as alarming as I did. At that point, I made it my goal to revive the stories of extraordinary women, highlighting the ways that they transformed the times in which they lived and the world beyond.

It’s important for women–and men–to have a better sense of the contributions that women have made to our world.

Q. How are the stories of Aspasia and Mary Nisbet Elgin relevant to women today?

Aspasia lived some 2500 years ago, and Mary lived 200 years ago. You’d think they had little in common, but women’s issues and concerns remain constant through the millennia–relationships, birth control, pregnancy, child-rearing, the place of women in society, and women’s fundamental rights. I wrote about these two women because, firstly, their experiences resonate quite hauntingly, and secondly, because while women generally have more rights and status today, at least in much of the world, our concerns are the same as those women. Both Mary and Aspasia defied social convention, which also makes them extremely identifiable to women today who have lived through so much social change. I am absolutely passionate about illuminating the truth of the female experience, and for many reasons, that truth remains quite static, I’m afraid.

Q. What are you working on now?

My next book will incorporate lore, mythology, and metaphysics, reflecting my interests in all those things. It will again be historical fiction told from a female point of view, but it will also be quite a departure, though one that I believe my readers are pre-disposed to like. That’s all I can say at the moment.

Q. Do you think the Elgin Marbles should be returned to the Greek government? Is there an argument to be made for the Marbles to stay in the British Museum?

Prior to the opening in Athens of the stunning new Acropolis Museum with a spectacular gallery that faces the Parthenon, I think the British had a pretty good case. After all, Parliament put Lord Elgin through grueling hearings to determine if he acquired the marbles legally. (Whether he did remains a subject of fierce debate, but at least Parliament tried to do the right thing.) The British have been the marbles’ steward for two hundred years, and the British Museum is not only a fantastic and free museum where people come from around the world to visit, but it’s also a center for scholarly study. The British have made these treasures easily accessible to the world in a very democratic way for a very long time. That said, it is inescapable that these treasures should be reunited with the building for which they were created. I agree that returning the marbles does open a can of worms as far as setting a precedent for who owns what in the world of art. If this idea of returning everything to its place of origin is carried out to its logical conclusion, the Louvre and other museums like it will soon be virtually empty. No one wants that. But the marbles, because they were taken from a structure that is still standing, represent a special case. Plus, it’s an emotional thing. One simply senses that they must go home!

Q. The themes of ownership and possession are felt throughout STEALING ATHENA, both in an artistic sense (with the marbles) and in relationships (Aspasia being a courtesan; Mary being an heiress). Do you feel that both Mary and Aspasia reject or accept the conventional notions of ownership at the end of the novel?

Well, Mary was certainly passionate about retaining ownership of her fortune and retaining control over her body–both of which were at odds with the conventions of her day. In the early days of the 19th century, a woman was literally and legally chattel–the property of her husband. In Aspasia’s time, the same was true. I believe that both of these women embodied a sense of self-determination that was radical in their respective societies. That’s why they fascinate us, and frankly, why they fascinated people in their own epochs. Both attained notoriety, for sure. Both were wildly criticized and persecuted, but both received respect from very illustrious persons. These were women who wanted to transcend ownership and own themselves. And let’s face it, there are women in multiple cultures in the 21st century who are still struggling with the very fundamentals of human rights and freedoms. Women–even privileged women–are still struggling to find their comfort zone in society.

*****

Portions of this interview with Karen Essex were taken from a conversation with Lynn Rosen on holdencalling.blogspot.com.

*****