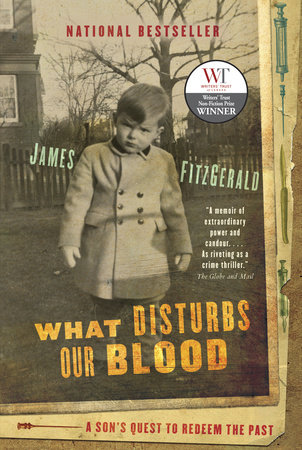

Author Q&A

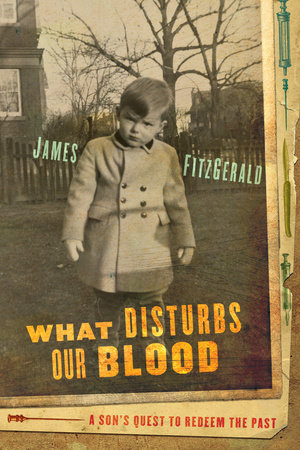

What motivated you to devote fifteen years of your life to researching and writing your book?

It was a case of emotional necessity. If I hadn’t attacked the subject, it would have attacked me. As a child, I knew nothing of my grandfather Gerry FitzGerald, a heroic figure in public health in Canada and abroad, who died under dark, mysterious circumstances in 1940, ten years before my birth. His son, my father – also an eminent doctor – never spoke of Gerry.

As a kid, I could feel something powerful under the heavy silence and as I grew up, it only intensified. As I watched my father crack up in front of us, right at the peak of his own professional success, I knew there was an elephant in the room – my grandfather – but everyone was pretending not to notice.

That was the genesis of my quest to understand my Irish-paternal legacy – an inseparable mixture of brilliance and madness. And probably why I became a writer.

How do your family members feel about your probing into painful family secrets?

Initially, they felt everything from ambivalence to outright disapproval. My younger brother was largely supportive, but my older sister had a harder time for completely understandable reasons. At age twenty-one, she had saved our father’s life after he tried to kill himself by injecting morphine. This event was like an exploding time bomb in the family, but down came the curtain of silence. I understand why we humans fall into states of repression and denial – we can bear only so much reality. So everyone colludes in “keeping up appearances.” But we pay a steep price – the price of re-enactment.

My father’s sister was a lifelong alcoholic and so her two adult children, my cousins, were also not thrilled with the prospect of family troubles being served up for public scrutiny. But for me, right from the start, it was all about confronting the unconscious generational cycles and the possibility of healing; never was I interested in judging or blaming anyone. At the same time, I was following the dictum of the novelist John Fowles, who said: “If you want to be a writer, you must kill your parents.” Meaning you can’t compromise yourself; there’s always a risk you will alienate people close to you, but it’s a necessary risk in the service of one’s own integrity.

I always felt that, as a family, we had nothing to be ashamed of – in fact, much to be proud of. And now, with the positive reception of the book, including a major literary prize, the original concerns of the family have faded away. I administered just the right amount of truth serum, I guess.

Your grandfather and father, both accomplished doctors, each suffered terribly under brutal psychiatric regimens of drugging and shocking that ultimately only worsened their suicidal despair. Yet you personally benefited from Freudian-oriented talk therapy; in fact you suggest it may have saved your life. Can you speak about these radically different approaches to helping the so-called mentally ill?

For complex reasons, most of the media and academia has reduced Sigmund Freud to a caricature of a dated, sexist Victorian patriarch, and therefore easy to dismiss. Yet his revolutionary ideas about the human mind will endure and continue to evolve. Freud was the first anti-psychiatrist, challenging the dominant idea that emotionally conflicted human beings must be reduced to nothing more than malformed brains or biochemically imbalanced bodies that are best drugged or shocked into “normality.” He challenged the overly scientized idea that our troubles and disturbances are symptoms of a “disease” that must be treated by the medically trained alone.

He knew that it is largely human relationships that originally damage us – and it is ultimately human relationships that heal us. Tragically, modern psychiatry has thrown out the relationship part of the story – and I think it’s no coincidence that rates of depression are soaring. Our relentless, go-go North American society is addicted to the quick fix for any and all perceived problems; long-term enterprises like self-reflective, [in-]depth psychotherapy are still viewed with suspicion, fear and even outright contempt. There are countless people out there who are just stressed out and need someone to confide in, but they are quite rightly wary of being dissected or “analyzed” by some white-coated, schizoid robot. I can understand the caution, because there’s a lot of quackery out there.

Unfortunately, the media tends to support the misguided idea that only MD-trained “experts” are qualified to help the so-called mentally ill. But at its best, and with the right guide, humanistic non-medical, face-to-face psychodynamic psychotherapy can be transformative. It changed me, and many people I know. It’s really all about pursuing self-knowledge through a sustained and compassionate conversation, getting acquainted with the richness of our unconscious life . . . what’s more interesting and rewarding than that?

Canadians seem to suffer from historical amnesia regarding our global achievements, in medicine and in other fields. Few of us know that beginning in the 1920s and ’30s, Canada led the world in public health and preventive medicine, largely due to your grandfather’s vision. Do you have any idea why we still tend to cut down “the tall poppy”? Or is our national “success-phobia” starting to change?

There are signs we are slowly shifting. For example, the blossoming of Canadian literary culture and the celebration of our best writers are relatively new developments. The 2010 Winter Olympics in BC showed a new aggressive side to national personality that was hitherto mostly passive-aggressive. Part of our dilemma is that we need to define ourselves against the American worship of the individual and their over-the-top celebrity culture. We are a cautious breed, more comfortable with a collective, egalitarian sensibility. Anyone who “gets too big for his britches” we cut down almost reflexively; it’s such an engrained habit. Maybe it stems from our immigrant experience in the frozen, brutal Canadian wilderness; to survive, we needed to rely on each other equally.

My grandfather was a microcosm of the phenomenon. He and his peers were self-effacing altruists, sacrificing themselves for the greater good of the community. The demanding work of public health – wiping out infectious diseases, etc. – was considered a team sport and no one was comfortable being singled out for special praise.

In his own case, my grandfather suppressed his own personal needs to the point of catastrophe. Perhaps it was the shame and “weakness” of his suicide, right at the peak of his success, that help explain why his memory was all but erased from our national consciousness. At the same time, we colonial-minded Canadians still have a hard time imagining we can be the best in the world at anything, let alone boast about it – except perhaps hockey and banking.

So it’s a conundrum: a saviour of countless lives is widely hailed as a success, a winner, a hero; when he kills himself, he is a loser, a failure, a nothing. As if all that he achieved never happened.

Your first book, Old Boys, exposed a sexual abuse scandal at Upper Canada College and sparked the criminal conviction of three former teachers and a successful multimillion-dollar class action suit against UCC. In your new book, you reveal many dark secrets within your own family. In a WikiLeaks world where confidentiality and invasion of privacy is a hot topic, is “full disclosure” of secrets, whether family or institutional, always the best policy? Or are there certain instances where discretion is the better part of valour?

I grew up in a secretive family. Besides the hush surrounding my paternal grandfather, my mother had worked as a decoder of secrets for MI5 during World War II. Twenty years passed before her job was declassified and she could tell her children about it. So a fascination with the dynamics of secrets is in my DNA.

From the beginning, I believed “full disclosure,” especially breaking down the “protection rackets” around emotional issues, was always the best policy – a reaction to the lid being nailed down so tightly in my own life. I still believe that, with only a few rare exceptions. Some argue that reporting suicides, for example, can induce a “copycat effect.” I think that’s debatable. We still err too much on the sides of sanitizing or sentimentalizing human frailty.

Most of us have something to hide, but hopefully we will think twice before we cast the first stone, blaming others for something we ourselves carry. Obviously I am not advocating an “outing” policy under all circumstances; there is such a thing as confidentiality and people understandably resent what they feel is an invasion of privacy. I guess it’s a question of whose privacy is being invaded and why. Public shaming is a useful journalistic tool, as long as it’s directed at the right people – usually the powerful. Unfortunately, most of the powerful are shameless.

Attending a private school like UCC, that incubator of the English Canadian power elite, sensitized me to the positive and negative of power. In my oral history of the school, I simply let people talk and recorded their subjective stories. If you genuinely listen, people will talk, often from a profound and honest place, depending on the person’s character, of course. We keep secrets even from ourselves, Dr. Freud reminds us, but if we talk freely, we start to hear ourselves saying things that suddenly feel like news. I did not expect to hear as much angst as I did – suicides, addiction, sexual abuse – amidst positive and inspiring stories as well.

I had no idea at the time that the book would spark the criminal conviction of several teachers for the sexual abuse of dozens of former students. I was just naively skimming the surface, not fully aware of the monsters below. When the publication of the book gave even more people permission to come forward, the floodgates opened – despite UCC’s attempts at cover-up. I was struck by some of the responses to the book from people outside that exclusive private school world – a weird combination of envy and contempt for the victims. They are part of an elite, so what are they whining about?

I think that’s partly why in my latest book, I decided to invade my own privacy – to try to show that whether it’s family or school or society at large, ultimately it’s all about weathering storms of truth-telling and emerging stronger and healthier.

Your two books cast a spotlight on the strengths and foibles of the privileged classes. Do you see yourself as anti-elitist?

I’m in favour of a healthy elite, because they wield power over us. A healthy elite entails a healthy conscience, for a start. As a young journalist in the 1970s, I was inspired by the lessons of the Watergate scandal and the power of the media to bring down corrupt leaders. We embraced all the noble journalistic mantras of the time: “Afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted”; “Speak truth to power,” etc. All fast disappearing from our corporate-dominated media universe, sad to say.

Yes, historically our elites have let us down, yet we will always need leaders with vision. Tragically, the elites are far more self-serving these days; it’s enough to make me pine for the quaint Victorian days of noblesse oblige and the values of my grandfather’s generation when “quiet philanthropists” did not insist their names be carved into the hospitals, libraries and schools they funded. There was an inescapable element of condescension and patronage, but at least they embraced the concept of obligation to a larger public good. At least there was a relationship between the elites and the rest of the world, a channel between the private and public.

Ideally, journalists should embody the nobler side of elitism: outsiders who penetrate the enclaves of the insider and report back to the citizenry; or insiders, or whistle-blowers, who export the bad or good news to the outside world. To use a crude Freudian analogy, the superego, the conscience, opens an honest channel of communication with the id, the masses, in order to inform and maintain a healthy collective ego. The ongoing erosion of the middle class and the growing polarization of rich and poor symbolize our current lack of balanced dialogue within the body politic. The elites are generally abdicating their responsibilities, and the media elites are as much to blame as anyone.

Is the act of writing inherently therapeutic for you? Or is it a largely painful process?

I suppose both. Suffering is an integral part of the human condition. I suppose I’m a bit old school when I say that, assuming we are adequately fed, clothed, housed and employed, at least a modicum of emotional suffering is good for us. I hate the phrase “building character,” but I think pain is a key part of creating a conscience. Nor do I think our goal should be to wipe out all suffering, as the druggers and shockers would have it – it’s the source of our creativity, our humanity, our capacity for empathy. And that’s what the best kind of therapy can do – helping us tolerate, bit by bit, previously intolerable feelings, which in turn makes us stronger.

Writing is close to torture for me, but that’s because I’m still far too much of a perfectionist. I still feel the shadow of a nasty Brit looming over my ten-year-old shoulder with a cane, poised to smack me for my faulty grammar. The best part of a book is when it’s over. As people respond, wonderful connections unfold; in that sense, a book is never over, it’s a living organism. Even being attacked is far better than being ignored – you know you have successfully afflicted the comfortable and the smug. The simple power of the written and spoken word to move people never ceases to amaze me.