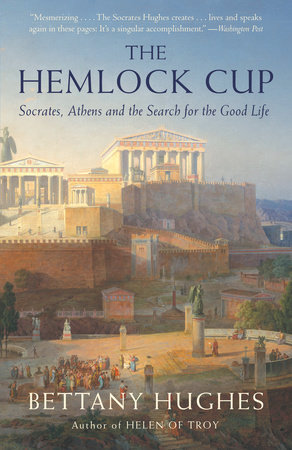

The Hemlock Cup

By Bettany Hughes

By Bettany Hughes

By Bettany Hughes

By Bettany Hughes

Category: Ancient World History | Philosophy | Biography & Memoir

Category: Ancient World History | Philosophy | Biography & Memoir

-

$22.00

Feb 14, 2012 | ISBN 9781400076017

-

Feb 08, 2011 | ISBN 9780307595294

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

The Inheritance of Rome

Vanished Kingdoms

Ghost on the Throne

Lords of the Sea

The Ancient Mediterranean

I Promise to Be Good

Slide Rule

Mountains of the Mind

An Old Captivity

Praise

“Fascinating. . . . What Bettany Hughes provides is something vital: a life and times of Socrates that is so richly textured, flavorful and atmospheric that it makes human this most enigmatic of all philosophers. By the end of her book, we can almost see and smell the man, with all of his quirks and foibles and questioning brilliance.” —Walter Isaacson, The New York Times Book Review

“Bettany Hughes’ biography is far more than just that: this tour de force is a vivid political and social history of Athens in the 5th century BC. Hughes evokes a city steeped in change, looking past the Golden Age of democracy, new wealth and power to the reality of a century tempered by war and infighting. With the plan of his life as a backbone, the book covers the whole experience of 5th-century Athenians, yet paints a picture of Socrates as a marvellous eccentric, paddling the streets barefoot, conversing with strangers and refusing to conform . . . this approach produces an extremely exciting narrative. Descriptions of Athens’ legal system aren’t dry but dripping with colour; the city itself is dirty, smelly, defiantly alive. And what other historian has spared a thought for the buttock pain of ancient jurors sat on hard stone seats in court? This is not a study of Socrates’ philosophy but his world. As thought-provoking as it is thrilling, the book is a beacon for the relevance and interest of classics today.” —The Times (London)

“Bettany Hughes’s terrifically readable life of Socrates is more than just a life; it is also an evocation and explanation of the world that created him, and over which he would come to have such influence. . . . The Hemlock Cup makes a vivid and persuasive case for the study of Socrates as a valuable means to understanding how our way of thinking about our own world came to be, and a guide to how we might understand it better.” —The Independent on Sunday (UK)

“A beguiling book. . . . Hughes triumphs again. This is history, and historical reconstruction, exactly as it should be written. . . . The Socrates Hughes creates is ultimately a towering yet intensely human figure. He lives and speaks again in these pages: It’s a singular accomplishment.” —The Washington Post

“Delightful . . . Hughes presents a high-octane account of Socrates and his age. . . . Do read this book, both because of its marvelous storytelling and because it will stimulate a desire to learn more about the ancient world.” —The Wall Street Journal

“Bettany Hughes has done it again; she brings to life not only Socrates himself but the whole of Periclean Athens. Here is a work of dazzling erudition which remains hugely readable—what more can one ask?” —John Julius Norwich, author of Byzantium

“No one before Bettany Hughes, a highly accomplished communicator, has thought to weave Socrates’s examined life into quite so rich and dense a tapestry of democratic Athens’s teeming high-cultural and mundane experience. . . . Hughes’s enormous energy and enthusiasm are infectious.” —Paul Cartledge, The Independent (UK)

“An invigorating, tremendous work of scholarship. . . . A smart and entertaining ‘biography’ of Socrates as shaped against the great experiment of democracy in 5th-century BCE Athens. . . . Hughes thrillingly navigates the life stages of her subject.” —Kirkus Reviews (starred)

“A compelling study of an exceptional man’s relationship with the one community that had a hope of understanding and accepting him. There’s some terrific and passionate writing about a philosopher whose heroism is unquestionable; and as lively and learned an introduction to classical Athens as you could want.” —The Daily Telegraph (UK)

“This is a lucid, erudite, and compelling work that brings Socrates and his city to life, offering a fresh and illuminating perspective on their times . . . A fruitful melding of informed and nuanced historical narrative and personal observation that succeeds marvelously in realizing its bold ambition.” —Weekly Standard

“The brilliant cultural historian Hughes has again produced an intriguing and entertaining biohistory of one of the most important individuals in the ancient world. . . . She brings to life the social, political, economic, literary, and military realities of Socrates’ society, in particular the centrality of the agora, [and] aptly conveys the continuing urgency of Socrates’ devotion to the inquiring mind.” —Publishers Weekly (starred)

“There are certain historical figures whose lives merit perpetual reexamination because their impact continues to reverberate century after century. . . . Not only a lively and eminently readable biography of Socrates the man, but also a vivid evocation of Athens, the city-state on the cusp of originating many of the greatest precepts of modern Western civilization.” —Booklist

“One can plunge enthusiastically into the seething world inhabited by Socrates that Hughes recreates for us. . . . This is the grand sweep of Athenian history during its most politically inventive and culturally exciting period. . . . Irresistible.” —Literary Review (UK)

“The life of Socrates becomes a peg from which to hang a vivid depiction of Athens in its golden age, from the pinnacle of its greatness to the abyss of its ultimate defeat. . . . Hughes’s prose is the literary equivalent of CGI, re-creating for the reader a sense of the clamour and dazzle of the classical city that has rarely been bettered. . . . Hers is an ancient Greece that is authentically cutting-edge.” —The Observer (UK)

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In