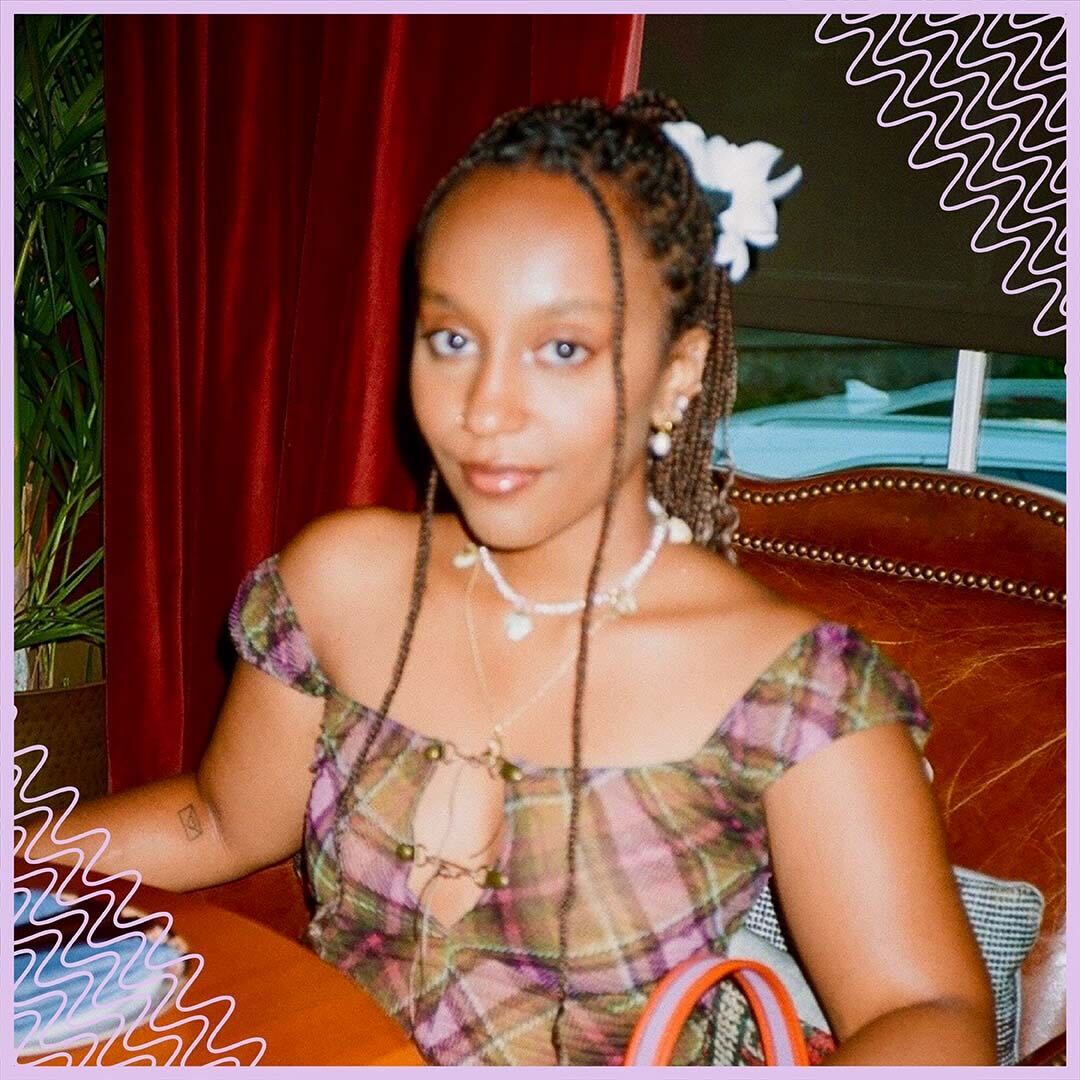

Nardos Haile is a Brooklyn-based culture writer and critic who works as an associate editor at Impact Media. She’s on a mission to regain her attention span after years in media at publications like The Associated Press and Salon, where digital media took over her life. She is passionate about media literacy, critical thinking, and connecting with readers through thought-provoking, visually appealing storytelling about her personal experiences and pop culture. You can find her on Instagram.

Writing has always been a sacred practice for me. My skills were a quiet secret when I journaled at 13. Now at 26, I feel an inexplicable rush when my hands sting from the clacking of my keyboard, as I shape sentences on a ticking deadline. This sense of purpose has sharpened over the last several years as I have grown more comfortable in my uncensored voice.

I’ve never been able to hide behind the richness of my words. They have always shown a vulnerability in me that cries for the world and its people.

So, I won’t hide here either. The truth is, Black women writers are disappearing from the workforce right in front of our eyes, and it terrifies me.

As diversity efforts dwindle in a post-2020 U.S., this racial regression and reckoning have reached Black women, too. Between April and July, 300,000 of them left the workforce, and I was one of them.

A media layoff shook the core of my identity and stability. I realized that across industries in the U.S., the very Black women at the forefront of shaping culture, politics, and intellectual thought, criticism, and reporting in this country are bearing the brunt of this social and political upheaval.

As literacy rates fall, the truth has become easier to distort, and our access to education and books is growing increasingly policed and politicized. It has never been more important to be a conscious writer and reader.

I think back to the legacy of writers like the late Toni Morrison, who paved perilous roads for us through her sharp mind and intentional storytelling. Her work and presence are only amplified in moments like this, where it’s vital to be a Black woman writer despite the world’s refusal to handle us with care.

Morrison understood this. She stood firm and refused to cater to whiteness. Her career remains a model for what Black women can achieve by paving their own way and never backing down to the gatekeepers determined to erase our visibility.

A figure like Morrison, who was Black and a woman, and a writer, challenged a white publishing industry in the twentieth century. The complexity of her identity and art spilled out into complicated, meditative stories like The Bluest Eye, Song of Solomon, Sula, or Beloved.

Morrison revealed the generational trauma woven into Blackness through the legacy of slavery and white supremacy. She also showed the depth of love and healing possible through connection and understanding.

In my own life, I have seen Black women tap into this endless well of radical empathy shaped by the layers of our experiences. These experiences hold many complexities, and being undermined is an unfortunate part of them.

Morrison spoke to this in a 2003 profile in The New Yorker. She noted that because of her identity, “I’m already discredited, I’m already politicized, before I get out of the gate.”

“I can accept the labels because being a Black woman writer is not a shallow place but a rich place to write from,” she said.

Her identity “doesn’t limit my imagination; it expands it. It’s richer than being a white male writer because I know more and I’ve experienced more,” Morrison said.

The author understood that questioning our voices, our art, and our written and spoken words is an easy way to dismiss our work, values, and perspectives.

Which is why I worship Morrison’s many challenges. As Namwali Serpell noted in Slate, Black womanhood is where stubbornness, demandingness, inconvenience, and complexity meet. This is found in Morrison’s word choice, her careful punctuation, and her political and social thought in interviews.

Morrison spent most of her career defending the type of stories she wrote because they were always told through the lens of the Black experience.

To white critics, Morrison could only be a legitimate writer if she wrote from a white perspective, too.

“As though [Black] lives have no meaning, no depth without the white gaze. I’ve spent my entire writing life trying to make sure that the white gaze was not the dominant one in any of my books,” she told Charlie Rose in 1998.

Morrison said that, “my sovereignty and my authority as a racialized person had to be struck immediately with the very first book.”

There will never be another Morrison for this reason. She captivated us with her ability to reject the status quo, even if it meant fielding patronizing questions about centering whiteness in her work.

Despite her national acclaim and prolific writing, teaching, and publishing career, there were many moments where Morrison’s Blackness, womanhood, and intellectualism collided with the system. In the face of those incessant difficulties, she never backed down because she was just as headstrong.

Part of her determination lies in the fact that she recognized the immense value in her intellect, her work, and her experiences. If it’s one thing Black women writers can take solace in in this moment, it’s that our enduring persistence is a strength, not a barrier.