Interviews

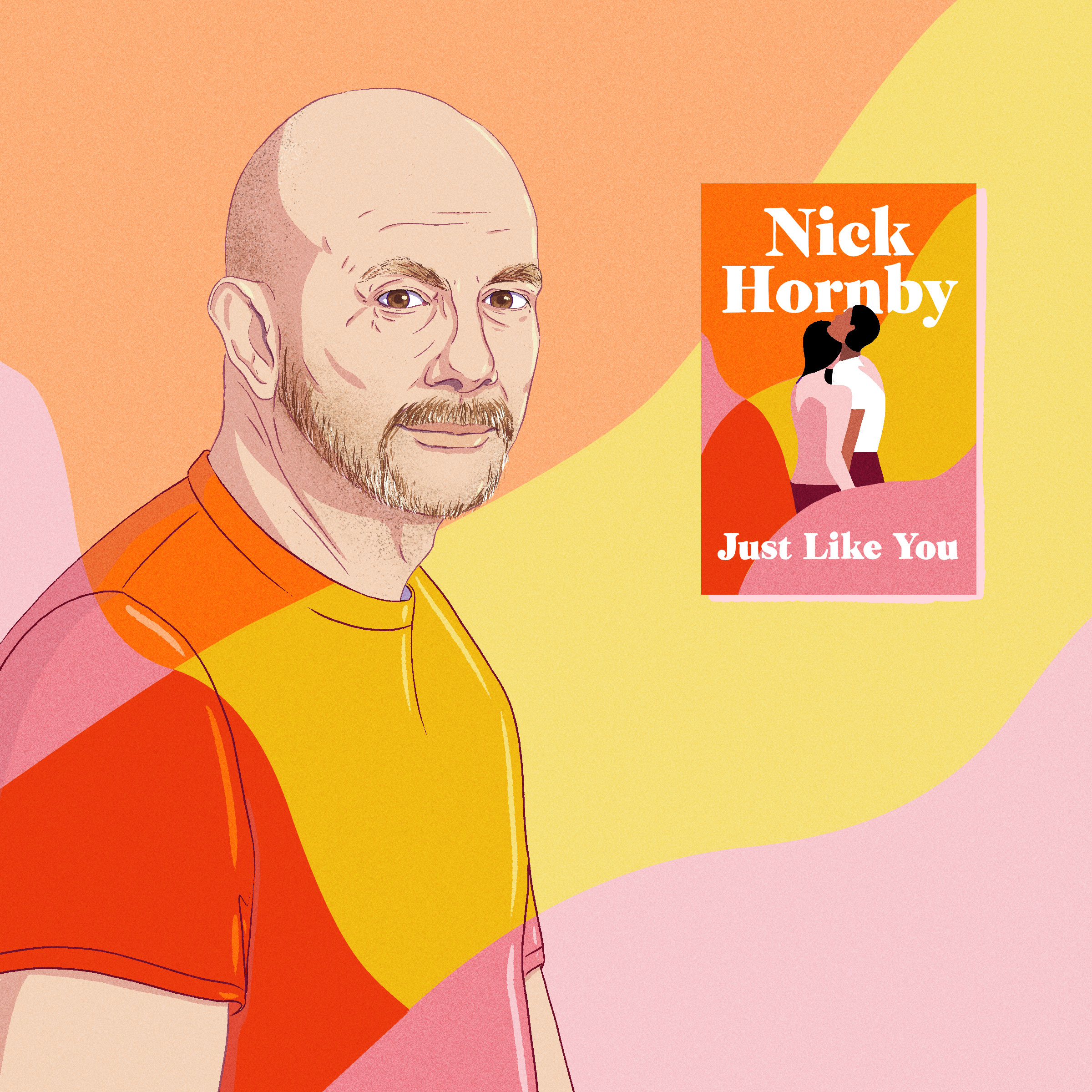

A Conversation with Nick Hornby

He shares his inspiration behind Just Like You and the changing landscape of storytelling

Just Like You is a brilliantly observed, tender, but also brutally funny new novel from Nick Hornby that gets to the heart of what it means to fall surprisingly and headlong in love with the best possible person–someone you didn’t see coming.

In his conversation with Sam Parker, Nick Hornby discusses his inspiration for the novel, the great storytelling outside of literature, and his role as a writer. Read the conversation in its entirety on www.penguin.co.uk.

Sam Parker: There’s an age gap of almost twenty years between Lucy (41) and Joseph (22), the protagonists of Just Like You. Tell us about that.

Nick Hornby: Well, I knew I wanted to write about a couple separated by as many things that could possibly separate a couple, within reason. The three big obstacles between them are age, education and race. It seemed to me, the more I thought about it, that age was probably the biggest obstruction to a relationship, or at least one that’s serious.

SP: Do you mean in a practical sense, or in terms of values and perspectives?

NH: Both, but mainly values and perspectives. And you know, it’s an interesting time to be writing about value clashes between older and younger people.

SP: Much is made of the gap between boomers and millennials. Do you buy into that?

NH: I think you can’t not buy into it. My generation has to be one of the luckiest to have ever existed. I was born at the end of the 50s: most diseases were eradicated, there were no world wars and my educational opportunities were just unbelievable. I went to a state school, I went to Cambridge and every tier of my university education was paid for. So I can understand why younger people today feel bitter and I sympathize, while not really knowing what to do about it. I think they have a lot to feel angry about.

SP: Some of the scenes in Just Like You skewer the more narrow-minded opinions of Lucy’s middle-aged, middle-class friends. Is that purely observational, or did it come from fear of seeing them in yourself?

NH: [Laughs] I don’t know. I think if you’re a writer, you have an advantage – and I’m not talking about any talent I have, I’m talking about what my job actually consists of – which is being completely on my own, thinking about and observing my community. And of course, if you haven’t got anything else to do, you end up being a bit more aware than most people. I don’t have to teach kids, I don’t have to work in a hospital, I don’t have do any of those things that would occupy mental space. And so, to a certain extent, if you can’t get [observing people] right, then what the hell are you doing being a writer?

I think what writers want most is to be part of the cultural conversation, and that’s why they keep drifting around from form to form.

SP: You wrote an essay for Penguin.co.uk over lockdown about the importance of the BBC, and you have said you believe some of best writing today is on TV rather than in novels. It sounds like you’re quite happy with that?

NH: Yeah, completely. Ideas for education, entertainment, laughs, excitement, empathy… it will come out where it will. I think what writers want most is to be part of the cultural conversation, and that’s why they keep drifting around from form to form. That has happened throughout history. There used to be such a broad, big division between mass entertainment and more literary entertainment but those distinctions have become very blurred over the last few years.

SP: What have you seen recently on TV that’s hit those heights?

NH: I May Destroy You. That is a writing talent on fire. It’s so complex and so instructional about the world. And TV seemed to be the perfect form for it. Parts of it are a tough watch, as you’d expect, but there was also irony and humor and all sorts of things.

SP: Are you finding it hard to feel hopeful for the future at the moment with the Covid-19 crisis?

NH: I don’t think it’s going to make any difference to me professionally. It’s the teenage and early 20s people I feel the sorriest for. We can delay our holidays or whatever until next year, but there are so many markers for young people that have gone and are not coming back. Your study year abroad, your school prom, your Freshers week, your graduation… things that are such an important part of growing up that have been wrecked. My boys [Hornby has two teenage sons] and their wider group are being incredible pragmatic about it and have found distractions, but I don’t know whether it’s going to have a knock-on effect later on, none of us do.

SP: What can we expect from you next?

NH: No book for a while, but I’ve written a second series of [TV comedy] State of the Union, which features a different couple. I’ve also got this huge TV project that I’m not allowed to talk about yet as it’s sort of edging towards a deal, but it’s a show about music and about real people.