Excerpts

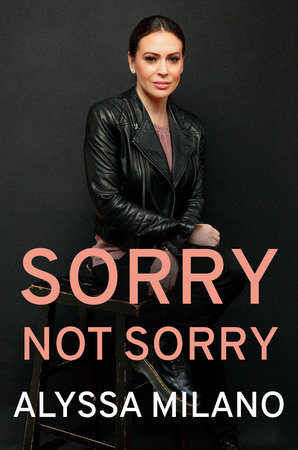

An Excerpt From Sorry Not Sorry

Alyssa Milano on what it takes to be a good ally.

In Sorry Not Sorry Alyssa Milano, actress and activist, delivers a collection of powerful personal essays that get to the heart of her life, career, and all-out humanitarianism. These essays are unvarnished and elegant, funny and heartbreaking, and utterly real. A timely book that shows in almost real time the importance of taking care of others, it also gives a gut-punch-level wake-up call in an era where the noise is a distraction from what really needs to happen, if we want to live in a better world.

There is an inescapable truth to being an ally: You do not truly understand the experiences of the group you are standing in support of. And you never will. You can’t—that’s the definition of being an ally: You’re outside that group, having different lived experiences, never having to worry about the things the people you are supporting worry about. If you did, you wouldn’t be an ally, you’d be living it. And because you can’t understand, and you never will understand, you’re going to get it wrong sometimes, if not often.

You have to be okay with getting it wrong, hearing that you got it wrong, and committing to doing it better.

It means acknowledging your own blind spots, diving into your own failings, and owning every last bit of them. It means feeling the failure, feeling the embarrassment and shame that comes with it—but then turning it into a positive instead of giving up. It’s a damned hard thing to do. But it’s so important.

In a coming chapter I’ll talk about one time I got it wrong, but it certainly wasn’t the only time. And I’ll probably keep getting things wrong as long as I use my voice. But hopefully in smaller and smaller ways, as I continue to do the work of listening, reflecting, understanding, and acting. And if there’s one big lesson I can impart on being an ally, imperfect at it as I am, it’s this: Do the work.

Being an ally isn’t showing up at a parade with a sign and then going home with a sense of personal accomplishment. Being an ally isn’t showing up at a demonstration outside a statehouse, chanting the same chants you chanted at the last demonstration, and then meeting up at a Starbucks after to talk about how you really did some good that day. That’s the easy part of being an ally. And if we center ourselves in our reflections, if we focus on the good work we did instead of the hard work we still have to do, we’ve failed in our jobs.

Let’s consider Black Lives Matter for a minute.

First of all, it’s a statement. A powerful statement that shouldn’t have so much power and meaning behind it. There should, in a perfect world, be nothing political or weighted or controversial about saying “Black lives matter.” It’s a statement of truth. It’s a statement of values. It’s a statement that should be universal, not only expressed with our words but manifested in our reality. When we expand on Black Lives Matter by adding “Trans” or “Women’s” before “Lives,” it should not make it any harder to express support for the movement or the terms that describe it. But so many are unwilling to say it in the first place. And that’s where being an ally starts.

I think about Ryan White all the time, and my journey into activism.

In the 1980s, a teenager named Ryan White contracted HIV from a blood transfusion. If you’re younger than thirty-five or so, you won’t know how terrifying those words were back then. HIV, which people mostly thought of as AIDS, the condition HIV can cause, was a death sentence, and so many Americans didn’t understand how it was transmitted. It played into our own fears and hatred, and we behaved as terribly as you’d expect. We took it out on the LGBTQ community, regardless of their HIV status.

It was a scary time to be a teenager, coming of age when sex felt deadly. And if it was frightening for me, it was terrifying for Ryan. It was also lonely and so very sad for him and others who lived with HIV or AIDS. This was the state of the world on the day I received a life-changing phone call. Ryan White wanted me to come on The Phil Donahue Show—which was the Oprah of its day—and kiss him to prove you can’t get AIDS from casual contact.

And I said yes.

Now, I don’t want to pretend that saying yes was easy for me. I knew the truth about HIV and AIDS, I understood what the scientists told us about the disease and how it was transmitted, and I understood that kissing Ryan on the cheek was a safe thing to do. But in my guts, in my secret heart, I was afraid. I had the prejudices that everyone else had. I had grown up hearing about this disease, how it was somehow immoral, how it was somehow a punishment, and how it was dangerous. Not from my family, but from the world around us. It was the first time I truly had to look deep into myself, see what was causing that fear, recognize my own failings, and work to overcome them.

This was not an easy thing for a teenager—especially a teenager who had been so blessed as me—to do. Teenagers are by nature the stars of their own world. When you’re trying to figure out how to be a self-sufficient human in your own right, stepping into the light for someone else is daunting for so many. And it was daunting for me. I wasn’t scared—at all—of Ryan or contracting his disease. I was proud to be able to help him. But this was my first step into the world of shining more light on others than on myself, and that was dizzying. I had no idea how much it would come to define my later life, but I did have the sense that it was a precipice and a catalyst for change.

And what became clear in the days and weeks afterward was how freeing it was to let all those fears go. It was freeing to replace that fear with love. It was an emancipation from my own prejudices and an invitation for something that could glow, and grow, and not only make the world better but make me better. I found in that place of transformation and progress and confrontation and discomfort in myself an invitation to a better me. The fear of HIV/AIDS and the social problems it caused were nearly as deadly as the disease itself. But if fear was part of the sickness, love was part of the cure.

And I found that to be equally true for the next thirty years to come.

Part of being a good ally is refusing to react. I’m a baseball fan. More than a fan—baseball is part of the very fabric of who I am. There’s nothing like spending three hours on a summer evening listening to the roar of a crowd, the sharp wooden crack of a well-hit ball, and the Dodgers beating anyone who comes to town. One of the things I think sets the pro ballplayer apart from a Little Leaguer is knowing which pitches you shouldn’t swing at. Sometimes you have to take a strike to learn who you are as a player. You have to see the pitch coming fast and inside and not charge the mound. Sometimes you realize you’re crowding the plate, and sometimes you realize that other people think you’re crowding the plate—and often those are the same thing. Taking a breath after a close strike, after an inside pitch, and reflecting on what you’ve learned about the pitcher makes you a better hitter.

Taking a breath when being confronted with a hard truth about yourself will make you a better ally. Not taking a breath leads to “not all men,” and “blue lives matter,” and all of these other bullshit trends that attempt to usurp the language of causes to bury their purpose. You are going to feel defensive when you are called out. I sure do. It’s something that is innate to who we are. When we feel threatened, we react. But the cool thing about being human, the point of being sentient, the thing that separates us from the creatures who hunt at night and live on instinct, is our ability to suppress our base nature, our worst instincts, and act in a way that makes sense in society.

There’s a story in the Bible I think of often when I need guidance as an ally. It’s the story of Shimei, the son of Gera. Shimei and David were not so sympatico at the beginning: Shimei cursed God and David and generally everything around him. There was division and enmity between the two, but David, as a wise king, let it be. Later, we find Shimei coming to David in full knowledge of his blasphemy and begging forgiveness: “For your servant is conscious of his sin: and so, as you see, I have come today, the first of all the sons of Joseph, for the purpose of meeting my lord the king” (2 Samuel 19). David’s advisers try to have Shimei executed for his sins; David refuses, accepting the reconciliation. Here in this moment of reflection, there can be peace and alignment and friendship between two people divided.

Now, there’s another part of Shimei’s story that I also reflect on. Shimei made his commitment to David to be a loyal subject and abide by his word. And for twenty years, he appeared to do so, and he and the royals were cool. But then, Solomon, who was the son of David and now king, told Shimei to build a house and stay there. Shimei built the house, but when some of his slaves escaped to a nearby town, he left to reclaim them. Solomon learned of his disobedience, his betrayal of his promise—one of many—and Solomon had him executed.

Shimei said words of commitment, but he did not hold them in his heart. He did not live by the promises he made. And they came back to haunt him.

As allies, we need to keep our promises. They must be durable, and they must be sacrosanct. If we don’t hold to them when they are inconvenient, when we think nobody is looking, when they get in the way of our own privilege, then they are meaningless. Worse than meaningless, they undo the goodwill we build together and set ourselves and other allies—not to mention the groups we purported to support—back further than we were when we made the promises. We have to be accountable not only to our partners, but to ourselves. I know I keep coming back to this, but it’s so important: We have to be comfortable with being uncomfortable.

I’m not the perfect ally. I’m not trying to lecture you here. I’m just examining the times I got it wrong and trying to prepare you for doing the same. Don’t let the discomfort deter you from doing what you know is right. Don’t let the criticism you’ll receive from your partners deter you—learn from it. Swim in it. Absorb the things that are earned, try to understand the things that are not, and use all of the information you glean to do better. To fail differently. To help.

Because that is what being an ally is about—helping someone else. Helping someone with a lower level of privilege than you achieve an equal level of privilege. It is never about you. It is never going to be about you. And if you find yourself in the Starbucks after the rally thinking about the good work you did instead of the good work you helped someone else do, you’re never going to get better at it. There is honor in helping. There is achievement in standing aside so the sun can shine on the people you’ve been blocking. There is reconciliation in surrender. And there is a better world on the other side, if we can just get out of our own way.

Excerpted from Sorry Not Sorry by Alyssa Milano. Copyright © 2021 by Alyssa Milano. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts

Excerpts