Author Q&A

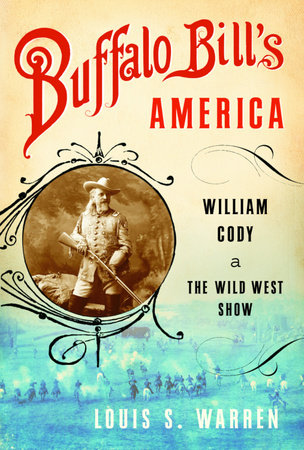

Q: What drew you to Buffalo Bill as a subject?

A: I grew up in Nevada, and I always enjoyed reading. Among my favorite childhood

stories were both western history and “strange but true” tales. Cody’s life was the perfect conflation of the two, and when I picked up his biography in the third grade, I was hooked. For a while, I read everything I could about Buffalo Bill.

I’m now a university professor and I teach western history to undergraduate and graduate students. Historians and cultural scholars rediscovered Buffalo Bill Cody about fifteen years ago, and have written volumes about how much his show did to shape

western mythology. Like many other western historians, I put Cody at the center of my

lectures on the myth of the frontier.

But over the years, I’ve found that each time I lectured about Cody, his story seemed weirder and more provocative. I began to have more and more questions about him, and the more I looked for answers, the more questions began to spring up. Was he a real

frontiersman? If so, how did he get the idea to become a showman? More than that, how did he come to envision his life as ongoing public amusement? Why was he so successful for so long? Why did Indians agree to appear in the show? Why was it popular in New York and in the East? And in Europe?

As I read more broadly, it became clear that although there were dozens of books about Buffalo Bill, most of them pursued his story no further than presenting it as one of those “strange but true” tales that fascinated me as a child (in which the weird facts are

ultimately never explained as anything other than “strange”). Don Russell’s deservedly

famous biography, The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill, was the last book to explore Cody’s military career in any depth, and even he pretty much threw up his hands when it came to explaining what inspired a buffalo hunter and Army scout to become a showman, and what transpired between the performer and his audience to make him such a success for so long.

Q: What kind of research did you do and did you have access to any previously neglected or underutilized sources?

A: In those cases where I revisited sources used by previous biographers, I was trying to bring a fresh perspective to the material, such as Cody’s press coverage and the scrapbooks compiled by him and his partners. Most of the research was in letters, Wild West show programs, and other documents in far-flung archives: the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming, the Denver Public Library, Yale University, the National Archives in Washington, D.C., the archives of the Palais du Roure in Avignon, France, and the newspaper collection of the British Library in London.

Along the way, I discovered many sources that no other scholars have used, including the extensive depositions of the Codys’ divorce trial in the Wyoming State Archives. The trial took place late in William Cody’s life. I found these documents particularly useful because of what they reveal about Cody’s personality. Although it is often said that by his latter years he could no longer discern the line between his real accomplishments and his many fictions, the divorce records show this to be untrue. Under oath, his testimony was very precise. When he told the story of his career, he was very down to earth, and he avoided embroidering his real accomplishments.

Some of my favorite research concerned the careers of Indians with the show. I had the opportunity to interview Arthur Amiotte, a famous Lakota artist, who is descended from Standing Bear, a performer with the Wild West show in the late 1880s. I also spoke at some length with Calvin Jumping Bull, another descendant of Wild West show performers. Both of these men were very generous with family history, and in both cases, I learned far more than I could have from written records alone.

Q: What makes this book different from any others written about Buffalo Bill?

A: There are a lot of Buffalo Bill books around, but this is the first since 1960 to take a hard look at the sources on his early life, including his careers as military scout and buffalo hunter. Most authors evaluate to some degree whether or not Cody was truthful about his own achievements. This book is the most thorough in evaluating his claims about those early years on the Plains, but importantly, it doesn’t stop there. This is the first book to explain not only what Cody actually accomplished and what lies he told, but why he told the lies he did, and how his real career with the Army and on the buffalo range helped inspire him to create a show in the first place.

This approach allowed me to explore the history and meaning of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show as a means to understand William Cody as a human being. Other biographers have treated the show as a weird afterword to his Indian fighting and buffalo hunting experiences. I start from the assumption that the Wild West show was his central occupation (it absorbed 33 years of his life) and his chief contribution to American culture. It was impossible to miss: an itinerant community comprised of hundreds of cowboys, Indians, vaqueros, and ultimately Cossacks, soldiers, and others. It toured North America and Europe, from California to Ukraine, for over three decades, performing almost daily for six months each year before audiences of 20,000 or more. It made him the most famous American in the world.

So my strategy has been to place this show at the center of Cody’s life story. Instead of treating it as a bizarre sequel to his frontier experiences, we learn how his frontier experiences inspired the creation of the show, and how he crafted it over succeeding years to resonate with audience desires. Just as important, the book examines why cast members–especially Indians and cowboys–took part. I learned a lot about Cody by investigating what his contemporaries and his employees thought about him and about the work they did with him. Many Lakota Sioux became cast members to earn money, to learn about the wider world and to teach other people about themselves, and to assert their independence from government authorities who tried to keep them on reservations. Cowboys, too, appreciated the show’s financial and travel opportunities.

The result is that Buffalo Bill’s America moves far beyond historians’ traditional arguments over whether Cody was hero or charlatan. I present him instead as an intuitive performance genius who realized as a young man that getting people to argue about him was the key to fame and fortune.

Q: Was it hard to get at the truth about a man who was so involved in creating personas and shaping his personal mythology?

A: Very. There were so many printed versions of so many different Cody stories that tracing the evidence for the real history proved very difficult. One of the biggest questions I had was why so few people who knew the truth in Cody’s day would challenge his version of events. The answer was that some of them did challenge him, but most thought his show was so amusing, and his legend so potent, that in a sense they wanted more to be a part of his stories than to undermine them.

Q: Why do you think so many people know who Buffalo Bill was but actually know very little about his impact on American history?

A: There are a number of reasons. As I point out in the book, there never was a time when Americans were united in enthusiasm for conquering Indians. Even during Cody’s life, there were critics who felt his battle reenactments could be tasteless and bloodthirsty. But because he told very powerful tales of his frontier deeds as Indian fighter and buffalo hunter, many Americans were not uncomfortable with seeing him as an authentic hero. To them, he had advanced the development of civilization.

But in the twentieth century, the public became yet more skeptical of frontier conquest. Today, relatively fewer people consider it heroic. So Cody’s connection to the frontier has made him a subject of suspicion, and most of us know so little about his show career because his Indian fighting and buffalo hunting make us reluctant to think about him. In a sense, his stories and our changing notions of American history have blinded us to his much larger achievement as entertainer and performer.

Then again, it’s possible to remain ignorant of his show career because his specialty was live performance. Once Cody was gone, the show was no more–there were imitators, but it was very hard to evaluate what his real contribution to American culture had been. There were a few film clips of the show around, but it was impossible to see the show itself, to understand what all the thrill had been about. Live performance was replaced by movies, which were a lot cheaper to make and easier to distribute, too.

There’s one more factor I think is important. Many people have a low opinion, or no opinion, of Cody because of our traditional love-hate relationship with showbusiness in general. On the one hand, we love showbusiness for entertaining us. On the other hand, we distrust it for distracting us from serious things like work and personal improvement. It becomes hard for us to take our entertainers seriously, and to acknowledge the hard work and vision that goes into the invention of popular amusements. This was a characteristic of the American public in Cody’s day even more than in ours, and it made his task very difficult. It was hard to be both an entertainer and a respectable person.

Q: In writing this book, what did you discover about Buffalo Bill that most surprised you?

A: Two things surprised me. First, I was surprised to learn how much the frontier West was a subject of debate and speculation in Cody’s day, and how much the public enjoyed arguing over what was real and what was fake in newspaper stories about the West and in the western exhibits and shows they saw. There was a vigorous tradition of democratic exploration of the Far West, and at a young age Cody learned to present himself as a credible frontier hero who could inspire a great deal of speculation about whether he was genuine or not.

The second thing that surprised me was how popular he was across the political spectrum. Most scholars have assumed Cody’s show was mostly a right-wing entertainment, but in fact, I found that Cody was admired–even adored–on the left, too. That’s really impressive, because political divisions were so deep at the time. Many commentators lament our partisanship today, but for three decades after the Civil War, the electorate was split almost perfectly down the middle. Republicans and Democrats feuded over “stolen” elections, the control of Congress and the White House, and just about everything else.

During all this, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West became almost a symbol of national unity. Certainly, there were people who personally disliked Cody (among them, his partner Nate Salsbury and the gothic novelist Bram Stoker). But for the public at large, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show allowed people to take whatever side they wished on the big political questions of the day and still enjoy the spectacle. Attending the show was almost a ritual of citizenship or a gesture of belonging to a broad public. Native-born Americans and immigrants, Republicans and Democrats, factory owners and laborers, conservatives and socialists (from George Custer’s widow to Karl Marx’s son-in-law) all numbered among Wild West show fans. Cody appealed to such a wide swath of the American and international public that he made himself into the era’s greatest mass-market attraction.

Q: Is there anyone alive today who you think resembles (not literally) Buffalo Bill?

A: I think the answer is no, and yes. Cody was a warrior who became an entertainer by reenacting a version of his own exploits and scripting them in a popular story of heroic achievement. In that sense there is nobody like him. Since his death, there have been few if any who could convey that sense of authenticity and action as well as Cody did. But even if there had been some, as I conclude in the book, the public’s diminished faith in social progress after World War I made it much harder for a single individual to claim to live a life of continual self improvement and advancement. What went missing was not just the man, but the story he acted out.

But then, in another sense, today there are many people like Buffalo Bill. In his day, he was unusual for envisioning his life as an ongoing story to be lived for the amusement of an audience. This idea became less strange in the twentieth century. Most movie stars try to project their on-screen personas back into their off-screen lives as a means of conveying their authenticity, of being believable to audiences.

But even more, in today’s world of the TV camera, hand-held video, and now digital internet cameras, the idea of life-as-performance has come to typify at least some aspects of everyday existence for a great many people. Newscasters and other television commentators play themselves every day. Reality shows invite us to believe we are watching real people engage real challenges (although they are nothing of the sort). Beyond that, the information revolution brought us new kinds of performance, in which people put cameras in their houses and allow viewers to watch them in their private homes. Of course, what is still missing from these examples is a heroic story of the sort Cody performed. These days, people play themselves, but I don’t think we would call their ongoing “stories” heroic, or even progressive.

I suspect most of us try to keep our public and private personas separate. But the idea of having a public persona that takes over your entire life is no longer so strange as it was in Cody’s day. In that sense, there’s a little Buffalo Bill in all of us.