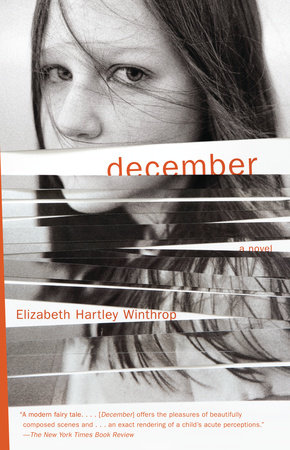

The following questions were posed to me by a specific book group that had read December, but they are representative of the general sorts of questions I’m often asked about the book, especially regarding the nature of Isabelle’s silence and the seeds out of which the novel grew.

Q: Did you battle with any OCD issues growing up?

A: When I was a teenager I struggled for years with anorexia. This was a very difficult time for both me and my parents and was actually the seed out of which December grew; I wanted to examine the impact something like anorexia has on a family, and not just the afflicted person. I chose silence for Isabelle rather than anorexia, or bulimia, or self-mutilation, or addiction, because I felt that readers would be less likely to have pre-conceived notions about it. I actually wasn’t familiar with selective mutism until after I started writing the book; Isabelle’s silence was, for me, a metaphor for any number of ways an adolescent girl might react to the difficult process of growing up. I know you are reading “The Story of Edgar Sawtelle” next, and I heard David Wroblewski interviewed recently. In his book, he makes up a kind of dog rather than having retrievers, say, or Labradors or poodles, for the same reason as I chose silence for Isabelle; he said he felt that if he chose a type of dog with which people were familiar, they would come to the page with a certain bias.

Q: Did you do a lot of research on selective mutism in preparation for this book? Is total silence both at home and school relatively rare?

A: My initial intent in writing this book was not to explore selective mutism specifically as much as it was to examine the impact of something like it generally on a family; in fact, I hadn’t heard of selective mutism until after I had started writing and my mother sent me an article about it from the New York Times because of the similarities between it and Isabelle’s silence. And while there certainly are similarities between selective mutism and Isabelle’s silence (and in response to the second part of your question), Isabelle’s silence is a bit more extreme than that of selective mutes, who, if they refuse to speak at home, say, will speak at school, or vice versa. Also, an important distinction between selective mutes and Isabelle is that selective mutism (as defined by the Selective Mutism Foundation) is characterized by the failure, as opposed to the refusal, to speak in select social settings. Isabelle refuses to speak in ALL settings.

Q: Which parent did you have more compassion for . . . the doer mother or the escapist father?

A: I had compassion for both. When a child is troubled, I think parents can have any number of reactions to the situation, whether, like Ruth, they choose to tackle the thing head on or, like Wilson, they cook up unrealistic, escapist schemes such as going to Africa. In Ruth, I wanted to depict the desperation a parent might feel when faced with something like this-a desperation only heightened by the nagging fear that she is somehow responsible. Ruth is convinced that Isabelle’s silence is somehow her fault, the result of something she, as a mother, either did or did not do. Partly because of this, she is all the more aggressively eager to make things better, to right the wrong, though sometimes her eagerness has the opposite of the intended effect; sometimes, she only makes things worse.

In Wilson, I wanted to depict the sadness and disbelief a parent might feel, as well as the helplessness. It pains Wilson to see Isabelle this way, and it pains him to feel unable to help her. He deals with her silence indirectly, “helping” her by setting up a zip line or planning a trip to Africa, partly because (and this pains him perhaps the most) he cannot face dealing with her directly. He dreads their lunch together, and hates himself for it; unlike Ruth, he is not good at carrying on a conversation with a wall. I think both parents love Isabelle enormously, and although their reactions to her silence might be at times wrongheaded, they are only human, and they mean only the best.

Q: Did you consider any other first words for Isabelle? If so, what were they?

A: Isabelle’s first word surprised me as author as much as it surprised her. I did not have an outline for this novel; each chapter grew organically out of what happened in the last, and while I always knew that Isabelle would speak, I did not know how or when or why until she called out for her father. For a while, I thought it might be that she would speak out on behalf of the dog, Maggie, perhaps if she found her very ill in the woods or something, but then Wilson was getting into that elevator, and Isabelle was afraid for him, and felt responsible for him, and the only way she could stop him was to use her voice. And when she did, it seemed right to me.

Her second word was more considered. I had to think about it. If you have been silent for nine months, and suddenly your silence has been broken, what happens? Do you resume speaking as if you’d never left off? Do you retreat back into your silence? I had to imagine myself into Isabelle’s position there in the lobby: she’s terrified, she’s got a very bloody nose, she’s just spoken, she’s totally overwhelmed, and then there’s Uncle Jimmy, the source of her fear, standing there with a large knife in his hand. “Fuck” seemed the right response, for a few reasons. I don’t think Isabelle, at age eleven, would necessarily throw that word around easily, but in this case, she’s afraid, and she can get away with it; she’s spoken, so she throws caution to the wind and says what she wants-but what’s also her natural reaction to the situation. Also, importantly, she is her mother’s daughter. Ruth isn’t sparing in her use of expletives, and so it seemed natural that Isabelle might take a cue from that. Her first word is for her father, her second is after her mother.

Q: Why do you never use the term selective mutism in the novel?

A: As I said earlier, when I started writing, Isabelle’s silence wasn’t necessarily meant to be selective mutism per se, with which I wasn’t yet familiar, as much as it was meant to be a sort of metaphor. I wanted to stay away from clinical terms. My interest wasn’t in the affliction/condition itself as much as it was in the impact of the affliction on the family.

Q: Why did the doctors give up on Isabelle? Are there no medical techniques or approaches to help selective mutism?

A: The doctors gave up on Isabelle because she wasn’t willing to be helped. She had no interest in interacting with any doctor; in fact, she only retreated further when in their presence. I am sure there are techniques to help selective mutism, but I haven’t researched them, nor was that my interest, really. I found it more interesting to explore what each of the main characters thought about this silence than what doctors could do to penetrate it. I also wanted the characters-particularly the parents-to feel completely unmoored and desperate and alone; the doctors can’t help, the school is pulling away, and it is up to them to help their daughter.

Q: Does Isabelle also have OCD? Are there links between mutism and OCD?

A: I think Isabelle has OCD, certainly; her compulsions sometimes even drive her own self a little crazy. She makes a bet with herself and has to cut her hair; she must arrange the shopping cart just so; she must cook dinner every Wednesday night; she considers the relation between numbers on a digital clock. As for links between mutism and OCD, I don’t have a scientific answer to that query. I would think it probably differs from case to case; I’m sure some selective mutes also suffer from OCD.

Q: Why did you select this theme for your novel?

A: While I was suffering from anorexia, I was painfully aware of the havoc I was wreaking on my family, yet I wasn’t able to stop starving myself. I hated myself for it, and I took this hate to punish myself further. Like Isabelle, I had “lost control of [my] control.” Years later, after I had finished writing fireworks, my first novel, I decided to write a story about a child who, just as I wouldn’t eat, wouldn’t speak. Silence was, for me, truly a metaphor, and I wanted to write this story (which turned into a novel) from alternating points of view: father, mother, child, to show how everyone was affected. I think this was for many reasons; it was an exploration, an explanation, an acknowledgement, and an apology.

Q: Isabelle’s parents were so patient. Was there anything else they could have done?

A: They were patient, and I think they did all they could. There certainly wasn’t anything I, as author, could imagine them doing that would have helped more.