Author Q&A

Q: Having grown up the son of an Austrian mother and American father with your childhood divided between the United States and Austria, how has your inheritance of these two cultures influenced your perspective on life and the world?

A: I often think that if I hadn’t spent so much time abroad, I’d have no perspective at all on America—I’d have grown up smack in the middle of it, with no sense that another way of life existed. Likewise, many Austrians and Germans I know have spent so much time thinking about (or avoiding thinking about) the Holocaust and its consequences that they’re not able to see it clearly anymore as a concrete event. As a child I often felt neither Austrian nor American, which often made me lonely, but it’s helped my writing to no end.

Q: Did your bi-cultural upbringing present any challenges to you as you developed the character of your protagonist, Oskar Voxlauer, a man who is Austrian through and through? Was it easy to divorce yourself from your own American values and perspective when writing his character?

A: Oskar is not Austrian through-and-through when The Right Hand of Sleep begins: he’s just returned from an exile of fifteen years in Soviet Ukraine, and the Austrian countryside feels far more alien to him than it does to me when I go back to visit my family. So if anything the American half of my life helped me to understand his intense, sometimes violent feelings of estrangement.

Q: This novel is based on a real life murder case in Austria during the German occupation of WWII as well as on some of what you drew from your grandfather’s diaries. Can you talk to the genesis of this novel and what drove you to write it? Is it autobiographical in any other ways?

A: The actual historical events you mention gave me a push of sorts in the direction I was to take, but the novel that resulted bears very little resemblance to them. Many aspects of my own life found their way into the book, of course, among them my first love affair. In a certain sense the faraway nature of the book’s setting allowed me to document my early adulthood with something approaching objectivity. Certainly I was able to show more sympathy for various people I’ve known (including myself) than I would have in a memoir. Little, however, of historical significance was taken from my family’s experience of the two world wars; my own family was far less glamorous in the 30’s, and less endangered, than the Voxlauers.

Q: Can you explain the title THE RIGHT HAND OF SLEEP?

A: I can’t truly explain it, as the title was taken from a line of German poetry, but I can interpret it a little. For me the phrase, which is used to describe Death’s messenger in the poem, captures beautifully the passivity and the menace that characterized the fateful year 1938, when Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany. ‘Right Hand’ for the political right, and the open palm that quickly closed into a fist; ‘Sleep’ for the sleep of reason that tolerated the Nazi takeover, and for the strange somnambulism that prevailed among the Austrian populace in general, and that enabled them all, enlightened citizens included, to believe in the possibility of happiness under Hitler.

Q: You tell this story through a mix of third-person narratives, first-person flashbacks, and dialogue that is indicated by unobtrusive dashes rather than quotation marks. How did you want these literary devices to effect the overall spirit of this novel and its characters?

A: The novel is, in a stylistic sense, a tribute to the giants of modernism (among them Sherwood Anderson, Hemingway, Faulkner, and John Dos Passos) who to my mind brought the art of rhetoric in the American novel to heights never equalled since. The structure and look of the novel was intended to reflect this.

Q: You told an interviewer once that you “wanted to write about how desertion can be good.” Can you elaborate? Would you consider Oskar’s retreat into the woods upon his return to Niessen another form of desertion?

A: It was precisely Oskar’s flight from town that I meant when I said this. A born skeptic, paranoid, and outsider, and thus a born deserter, Oskar finally finds in the regime of Nazi Austria something worth deserting. At the same time, however, in the love affair with Else Bauer, he finds something he can’t bear to leave. This is what fuels the suspense and violence of The Right Hand of Sleep, and would appear to spell the protagonist’s doom.

Q: The critics have all praised the authenticity with which you wrote this story as young as you are. Having been born in the 70’s, far removed from the reality that was WWI and WWII, what challenges did your chronological remove from the period of this novel bring and how did you overcome them?

A: It was enormously difficult to recreate the world of 30’s Austria, so finally, after a huge amount of research, time and toil, I gave it up. Instead I created a world that resembles my understanding of the 3rd Reich, but springs more directly from my own paranoias, experiences, and dreams. This in turn gave the narrative its fever-dream-like quality, which is the thing I cherish most about the finished book.

Q: Rumor has it you wrote this novel under some pretty ghastly physical conditions—in a room with no heat, windows, or indoor plumbing. Would you like to elaborate? How did these conditions contribute to the creative process?

A: It’s all true—fired from my job in an art gallery, kicked out of my illegal sublet, I spent almost two years living in the basement of a warehouse under the Manhattan bridge. The temperature hovered at around 55 degrees, the only toilet was a block away, and the rats were so plentiful and so friendly that I spent my nights zipped safely up in a tent. Oskar Voxlauer spends much of the book in a dank, stinking cottage in the forest, so the advantages of my own living conditions in imagining his should be all too clear. I didn’t, however, think of them as advantages at the time.

Q: THE RIGHT HAND OF SLEEP was recently released in Austria. What has been the reaction to the book there?

A: The reaction there has been big and very favorable—with the exception of one reviewer, who hated it with an intense, almost religious passion. He called the book, among other things (roughly translated from the German) “a towering, terrifying orgy of kitsch.” Needless to say it’s one of the most enjoyable reviews I’ve ever read.

Q: What writers have been most influential to your own writing?

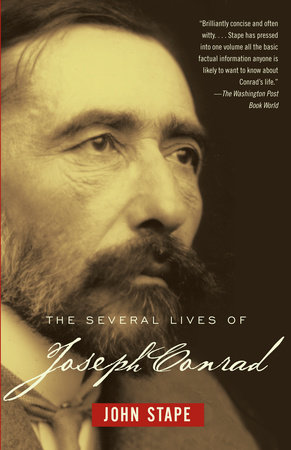

A: Among American writers (aside from those already mentioned), Edgar Allen Poe, Henry James, Walter Abish, Raymond Chandler, William S. Burroughs, Joan Didion, and Gertrude Stein. Peter Handke, the Austrian novelist, was a major influence, as were Joseph Roth, Günter Grass, and Ingeborg Bachmann. John Berger, the English novelist and art critic, should also be mentioned here, particularly his Booker Prize–winning novel G.

Q: If you were not writing, what would you want to do be doing for a living?

A: I think I’d like to be a flyfishing guide, or a rock-n-roll drummer. Or a chef.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I’ve just finished the first draft of a novel based loosely on the life of the notorious antebellum slave trader John Murrell. The novel begins with Mr. Murrell’s arrival in New Orleans in 1836 and ends with his arrival in 1861 in Hell.