The Book of Mormon Reader’s Guide

By

INTRODUCTION

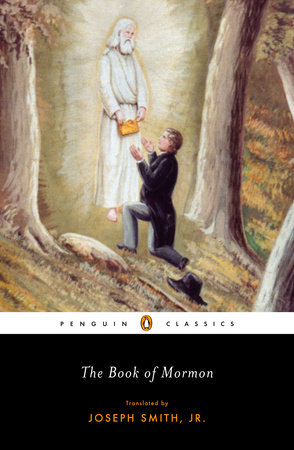

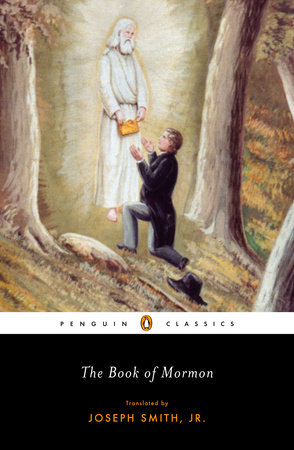

Since its initial publication in 1830, The Book of Mormon has stood as one of the most original and revolutionary works of faith ever written by an American. Believers, historians, scholars, and skeptics are virtually unanimous in their opinion that the church begun by Joseph Smith in upstate New York and that later flourished on the shores of the Great Salt Lake has indelibly altered the story of Christianity, both in the United States and in the world at large. Beyond such general assessments, however, there are few points regarding The Book of Mormon and the faith it has inspired on which everyone agrees. Even the simple question of authorship is a matter of ceaseless argument: did Joseph Smith conceive and write the book himself? Or was he, as he fervently claimed, led by an angel to unearth a collection of golden plates on which The Book of Mormon had been inscribed? And what of Smith’s personal motivations? Did he, as he assured a questioning world, translate and publicize the contents of the sacred plates as a servant of God, entrusted with a holy mission? Or, as his detractors claimed with equal vigor, had he perpetrated an audacious hoax, calculated to fuel his self-serving rise to demagogic power? Controversy has long raged as to the fundamental premise asserted by Smith’s purported plates: that centuries before the birth of Christ, a band of pious Hebrews, led by the prophet Nephi, fled the Middle East and sailed, by way of the Pacific Ocean, to the New World, where they established a sophisticated theocratic society and, eventually, received a visitation from the recently crucified Jesus. The Book of Mormon has always stood at the intersection between the impossible and the miraculous.

With this, the new Penguin Classics edition of The Book of Mormon, based on the last edition supervised by Joseph Smith before his violent and untimely death at the age of thirty-eight, readers have a renewed opportunity to revisit all of the fascinating questions that have surrounded The Book of Mormon and, indeed, to pose some new ones of their own. A work of astonishing historical scope, The Book of Mormon lends itself to a broad variety of readings. On one level, it is a sacred text that still informs the spiritual lives of millions of believers—both as a corroboration of the Christian Bible and as an indispensable supplement to the Bible’s historical and moral commentaries. From a quite different perspective, one that prefers to regard its accounts as fanciful and fictitious, The Book of Mormon can be seen as the product of one of the most fertile imaginations ever to express itself in print. For yet another community of readers, The Book of Mormon is a key historical artifact of the American past, speaking eloquently of the interests and needs of American society during the time when it first appeared—an era when countless Americans were seeking either a confirmation of their faith or a radical alternative to it. At a time of great religious enthusiasm and upheaval, The Book of Mormon struck some as a profound revelation and others as a shameless blasphemy. As a document of a growing, spiritually inquisitive nation and as evidence of the restlessness and contention that pervaded American religious thought in the 1830s and 1840s, it has no equal.

Still other readers, seeking to relate the current culture of America to its nineteenth-century antecedents, will find much fuel for debate in the Book’s sociological assumptions. In a time when a college education lies within the reach of most Americans and wealth is often deemed synonymous with success, it is fascinating to observe The Book of Mormon‘s uneasy regard of education and affluence. From the standpoint of an era in which both women and African Americans may seriously aspire to the White House, it is both remarkable and unsettling to explore Joseph Smith’s assumptions about race and gender. For every reader who has a firm, unspoken sense of what it means to be American or Christian, The Book of Mormon bears destabilizing witness that Americanness and Christianity are terms forever up for grabs.

During the brief, eventful life of Joseph Smith, Americans looked upon a dazzling array of Utopian communities and alternative systems of belief. Today, however, the Shakers, the Millerites, the Brook Farmers, the Fruitlanders, the Hopedale Community, and the Oneida Perfectionists exist almost exclusively in history books. Yet The Book of Mormon and those who honor its teachings remain strong. To discover some of the reasons why is among the more fascinating journeys on which a modern reader can embark.

Born on December 23, 1805, in Sharon, Vermont, Joseph Smith, Jr., grew up in western New York State, which was then experiencing a period of widespread religious awakening and enthusiasm. As an adult, Smith claimed that, when he was fourteen, God appeared to him, telling him that all the established churches of the time had departed from the true path of religion, and that Smith should join none of them. Seven years later, in 1827, Smith claimed to have discovered a collection of golden plates, buried in the ground, whose existence had been revealed to him by the angel Moroni. Smith averred that, with the aid of special stone and divine assistance, he translated the writings on the plates from a language he identified as “reformed Egyptian.” According to Smith, the writings on the plates comprised the original text of The Book of Mormon, which told of how a band of ancient Hebrews, at divine behest, fled the Middle East and sailed to North America, where they established a true prophetic Christian faith.

Smith published his translation of The Book of Mormon in 1830, claiming that it contained a pure gospel, untainted by the contaminations of the mainstream Christian churches, which The Book of Mormon describes as “the mother of abominations, whose foundation is the devil.” The same year, Smith organized a church in Fayette, New York, which he hoped to use to restore Christianity to its original footing. Community intolerance and financial difficulties compelled Smith and his growing body of followers to relocate repeatedly westward, with sojourns in Kirtland, Ohio, and Independence, Missouri. In 1839, Smith led his people to Commerce, Illinois, which he renamed Nauvoo. Converts to his teachings soon swelled the town’s population to twenty thousand, making it briefly the largest city in the state.

The Nauvoo community prospered until February 1844, when Smith, now mayor of Nauvoo, announced his candidacy for president of the United States. Disaffected by his ambitions and his acts of polygamy, a minority group in Smith’s flock denounced him in a newly created newspaper, the Nauvoo Expositor. Smith declared the paper a public nuisance, ordered the paper’s press destroyed, and declared a state of martial law. Illinois governor Thomas Ford charged Smith with treason against the state of Illinois and had Smith imprisoned in nearby Carthage. On June 27, 1844, a mob of about two hundred men stormed the jail and shot Smith multiple times, killing him. After Smith’s death, his followers divided. The larger portion, led by Brigham Young, migrated to the Great Salt Lake in the Utah Territory and founded the modern Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, which now claims more than 13 million adherents worldwide.

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In