READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

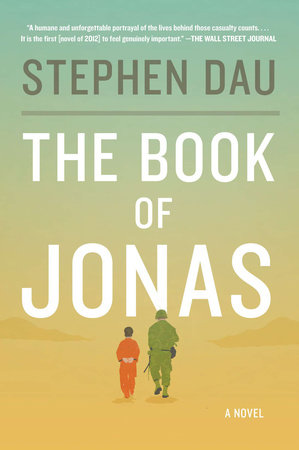

Set against the background of war in the Middle East, The Book of Jonas tells the remarkably intertwined story of three figures fate and war have brought together: Fifteen–year–old Jonas, who fled when his village in an unnamed Middle Eastern country was destroyed in a U.S. attack; Christopher Henderson, the American soldier who follows Jonas into a cave and saves his life; and Christopher’s mother, Rose, who becomes an activist working to help other families who have lost sons and daughters in war.

The novel is told in a series of short chapters that alternate between Jonas’s past and present, Christopher’s journal entries, Jonas’s sessions with his therapist Paul, and the efforts of Christopher’s mother Rose to find the truth about her son, listed as Missing in Action. This structure creates a kaleidoscope of perspectives and layering of emotions, all in response to the same overwhelming facts of war.

After his entire family has been killed, Jonas is sent by an international aid agency to live in America. Ironically, or perhaps providentially, he lands in a suburb of Pittsburgh, near where Rose Henderson also lives. He struggles to fit in with his adoptive American family and their disconnected lives, their children who, when they periodically emerge from their fog of video games and self–absorption, barely notice Jonas. Indeed, the daughter pats him on the head like a pet dog. At school he is mercilessly bullied until he fights back with a viciousness that lands him in therapy.

There, in response to his therapist Paul’s insistent questioning, the story of Jonas’s traumatic past begins to emerge. The savage, vengeful attack on his village; the death of his entire family, including his seven–year–old sister; his escape to a cave his father had prepared; and his meeting with Christopher. At first, telling his story, even in the barest outline, only makes things worse. After a visit to Rose where he offers a severely truncated version of what he knows about her son’s possible fate, Jonas takes his budding alcoholism to another level, engaging in binge drinking that leads to blackouts, fights with his girlfriend, academic suspension, and eventual arrest.

But it also leads Jonas to reopen the journal Christopher left him. The entries recorded in it—heartfelt, soul–searching, self–questioning—cast a new light on all that has come before, the actions of both Christopher and Jonas, and the larger trajectory of their lives. As Jonas finally seeks recovery from his alcohol addiction, his AA sponsor asks him if he thinks there is a higher plan at work in his life, if he was brought to America for a reason. And indeed, the novel itself seems to pose that question to the reader: Are the events of Jonas’s life random or guided by an unseen power?

The Book of Jonas is remarkable both for the story it tells and the way it tells it. Christopher and Jonas each commit acts that would seem to invite judgment, but Stephen Dau is much more interested in investigating the causes of their actions—and the extraordinary consequences that result from the unlikely intersection of their lives—than in moral condemnation. And by so deftly exploring the inner lives of Jonas, Christopher, and Rose—the torments each has suffered—The Book of Jonasoffers a nuanced and deeply reflective novel about the effects of war that are still unfolding around us.

ABOUT STEPHEN DAU

Stephen Dau is originally from western Pennsylvania. He worked for ten years in postwar reconstruction and international development before studying creative writing at Johns Hopkins University and Bennington College, where he received an MFA. His work has appeared in McSweeney’s and the Pittsburgh Post–Gazette, on MSNBC, and elsewhere. Dau lives in Brussels, Belgium, with his family. The Book of Jonas is his first novel.

A CONVERSATION WITH STEPHEN DAU

Q. Why did you give the book’s sectional titles religious resonances: Processional, Invocation, Remembrance, Communion, Confession, Atonement, Benediction, Recessional? Did you intend the book to have an essentially religious trajectory and for readers to consider the parallels between the novel’s protagonist and the biblical Jonah?

I’ve heard someone say that it’s reminiscent of a Catholic mass. I was brought up Presbyterian, and so it reminds me of a Presbyterian church service. Part of this device is practical. The story needed a structure, and the structure of a religious service allows for a certain amount of flexibility while still imposing an overall form. Beyond practical considerations, I came to see the book, or at least the act of writing it, a little bit like a prayer. That is the best way I can describe it. The religious imagery flowed out of that. The idea of sacrifice flowed out of that. The section titles flowed out of that. That’s the best explanation I can give for it. It’s a sort of prayer.

Q. How has your work in postwar reconstruction and international development influenced the writing of The Book of Jonas?

Working in development certainly influenced my fiction, mostly by giving me access to the practical, immediate effects of war on real people. After going to Sarajevo, I could no longer see people on the news reports as abstractions. It’s probably only natural that I started writing about them. But I wouldn’t call my fiction an extension of that work, other than to say that my interests and outlook now are similar to what they were then. Fiction is more creative, reflective, and documentary. It tries to mold reality, alter it, fit it into a manageable shape, and present it back to the reader as some sort of complete experience. In contrast, reconstruction or development seeks to deal with a specific situation to achieve a specific goal. These are not necessarily mutually exclusive endeavors, but they are not at all the same.

Q. This is your first novel. Could you talk about your process in writing, revising, and publishing it? Did you begin it while in the MFA program at Bennington College?

I had the idea for what would eventually become the book a few years before I went to Bennington, but I hadn’t done much with it. I went there with the intention of working on it more–or–less exclusively and coming out the other side with a complete (or relatively complete) manuscript. In terms of publishing it, I’ve been through my share of rejection, and have received some silly suggestions (“It would be more interesting re–written in first person,” or “You should name him Jimmy”). But I’ve been really lucky. I have a lot of writer friends who can swap horror stories about their publishing experiences. But ever since I signed up with my agent, Henry Dunow, who sold the book to Sarah Hochman at Blue Rider Press, I have had none to share. I could not have hoped to be in such good hands.

Q. How were you able to imaginatively identify with characters so seemingly unlike yourself: Jonas, a victim of war who has lost his entire family, and Christopher, a font–line soldier who has seen a lot of combat? Did you do a lot of research for the book?

I would research subjects as they came up. If I had a question, I’d either look it up or I’d talk to people. I did the research as a part of the writing, rather than something separate from it. So, for me the work was all tied up in the same bundle. The writing of it went along with the research of it, which went along with the rewriting of it in this effort to try and get it to look like what I wanted it to look like. In terms of imagining myself in those situations, I get the impression it’s a lot like what actors do. A friend of mine who’s an actor talks about allowing himself to live fully in an imagined world. I guess that’s sort of what I did, except I reported back on it in written form, rather than acting it out.

Q. What is your personal view of America’s involvement in Afghanistan and Iraq? Do you feel American writers have an obligation to address, or at least acknowledge, these wars in their work?

As you can probably guess, I thought the U.S. invasion of Iraq was one of the stupidest things the country has done in the past fifty years or so. We’ve only now, ten years on, seen the first real wave of fiction to come out of these wars. That’s a process that I think will go on. Afghanistan is now the longest–running war in U.S. history. As a country, America hasn’t really even begun to deal with what it’s been doing, and will be working through the fallout of these wars for years, probably generations, to come. I think the fiction will continue to reflect that. But I would never presume to tell other writers what their work should acknowledge or address.

Q. Why did you choose not to specify the country Jonas is from?

There are probably two reasons for leaving Jonas’s home country vague. One of them is very practical: I didn’t feel like I knew any one place well enough to stick a flag in the ground and say, ”This is where Jonas is from.” Unless you know a place very well, everyone who’s been there, and everyone who lives there currently, will inevitably have more information about that place than you do, especially if it’s some place you’ve just visited. You have to get it exactly, absolutely right, and I didn’t feel like I knew any plausible place well enough to be able to get it that right. The second, and probably more important, reason for leaving it vague is the fact that this is a story that could have happened in lots of different places, and so not specifically saying where it happens allows it to have happened in many places. It allows for a certain universality.

Q. Early in the novel, Jonas’s therapist, Paul, tells Jonas that “The past is gone, done. You memories can’t physically hurt you. But we need to explore them. We need to understand what happened” [p. 15]. How helpful do you think therapy can be for people like Jonas, as well as for returning soldiers suffering PTSD?

Therapy is only as helpful as the amount of honest work and self–examination one is willing to put into it. There seems to be a conception in the West, and in the United States in particular, that therapy is like a pill or medical treatment, as in, “Why don’t you go get some therapy and get yourself sorted out?” Like it’s an aspirin. But therapy is really only a tool or method of self–examination. If one is unwilling to do the often painful work involved, it won’t be much help at all. However, it can be incredibly helpful if one is willing to engage with it.

Q. Have you heard from soldiers, war victims, or activists like Rose in response to your book?

I have heard from quite a few. With one exception, they have all been incredibly supportive and seem to immediately understand the book and what it is trying to do. I am very grateful that they take the time to reach out to me.

Q. When Jonas is telling his story to Rose, he reflects that he’s not lying about the image of the moonlight, “at least, no more so than anyone who tells a story . . . The difficulty, he realizes, is inherent in the use of both words and memory. Their imprecision combines to make it nearly impossible for him to tell a true story” [p. 108]. Are all stories intrinsically “untrue”? In what sense does The Book of Jonas tell a “true story”?

There is a concept in quantum physics that I think is fascinating. If scientists are studying certain particles, they find that the act of observing them changes their properties. I think, as a concept, this applies to memories and to stories, at least in terms of effect, if not necessarily the mechanics behind it. The story I’ve told is not exactly the same as the story you’ve read, because you’ve brought a set of experiences and conceptions to the reading that are completely different from mine, and different from everyone else who has or will read it. Your perceptions are entirely unique. So I don’t know if “true” is the right word for it, because that word implies a measurable, objective reality. Maybe “honest” is better, because there’s an amount of subjectivity built into that word. The Book of Jonas is entirely made up. It’s fiction. As such, it’s literally untrue. But when I wrote it, it was the most honest story I was capable of telling.

Q. What’s it like being an American writer in Belgium? Do you feel detached from the American literary scene?

I do feel almost entirely detached from the American literary scene. I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing, though. It’s nice to be able to dip into it occasionally, and then dip right back out of it again. I feel a little bit like a foreigner when I visit America now, and I think that might give me a slightly different perspective on things, looking at the country from outside the echo chamber. I’ve lived in Europe for eight years now, so a lot of the cultural references that I would have once shared are disappearing or are dated. But again, I don’t think that’s bad. It seems to give my writing a certain objectivity that it probably wouldn’t have if I had remained in the U.S.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS