READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

MEET LARRY WELLER

What is this mighty labyrinth—the earth,

But a wild maze the moment of our birth?

(“Reflections on Walking in the Maze at Hampton Court,” British Magazine, 1747)

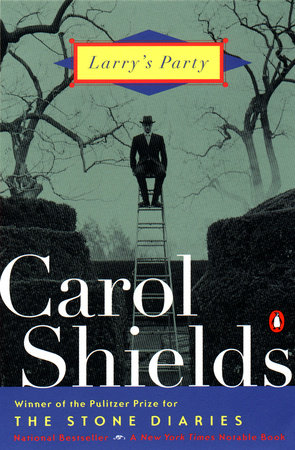

Meet Larry Weller. Born in 1950 to working class parents, he’s an ordinary guy. His life is punctuated by unremarkable events: marriage, the birth of a child, divorce, job changes, illness, and the death of his parents. Even the pockets of his own tweed jacket are stuffed with leftovers from his ordinary life: nickels, dimes, old movie stubs, and a gathering of gritty little bits of lint collected in the seams. The only extraordinary thing about Larry Weller is that he is the subject of Larry’s Party, the new novel from Pulitzer Prize-winning author Carol Shields that celebrates the twisting—and often chaotic—path of his life.

“By mistake, Larry Weller took someone else’s Harris tweed jacket instead of his own, and it wasn’t till he jammed his hand in the pocket that he knew something was wrong.”

Larry’s life unfolds before him as a series of mistakes and coincidences. When Red River College sends him a brochure for Flower Design, instead of the requested Furnace Repair, Larry learns how to arrange flowers for a living. When his date to a Halloween party wears an unappealing pirate costume, Larry’s eye wanders and falls upon a cute Martian named Dorrie. A year later, Dorrie accidentally gets pregnant and becomes the first Mrs. Larry Weller. Perhaps the most significant coincidence occurs on their honeymoon in England, where Larry allows himself to get lost in the Hampton Court garden maze. While halfheartedly navigating his way through the lush green labyrinth, Larry realizes that he revels in taking wrong turns, that “getting lost, and then found, seemed the whole point.” Mazes become not only Larry’s passion and life’s work, but also a mirror for Carol Shields’s winding, looping narrative and the episodic structure of Larry’s Party.

Carol Shields knows that life’s breathless moments of clarity arise unexpectedly, and that we all must cull wisdom—like Larry—from “sideways comments over lemon meringue pie, sudden bursts of comprehension or weird parallels that come curling out of the radio, out of a movie, off the pages of a newspaper, out of a joke.” Larry’s odyssey through life—and the reader’s journey through this novel—is random yet patterned.

At the end of the novel, Larry gathers all of his friends and lovers together for a party. Over roasted lamb and fine wine they banter about the meaning of life. Life, they say, is the ultimate maze, and a maze is “our thumbprint on the planet.” One guest observes that “at the center of the maze there’s an encounter with oneself…a sense of rebirth.” Ah…yes, Carol Shields seems to be saying. In spite of fate’s marvelously unpredictable inner compass, people often seem to get to the right place, which is the center of the self.

ABOUT CAROL SHIELDS

The youngest of three children, Carol Shields was born in Oak Park, Illinois, in 1935. She studied at Hanover College, the University of Exeter in England, and the University of Ottawa, where she received her M.A.

In 1957, she married Donald Hugh Shields, a professor of Civil Engineering, and moved to Canada. She has lived there ever since. In addition to raising five children, all now grown, Shields has worked as a professor at the University of Ottawa, the University of British Columbia, and the University of Manitoba. She lives in Winnipeg, where she is the Chancellor of the University of Winnipeg.

Shields is the author of several novels and short-story collections, including The Orange Fish, Swann, Various Miracles, Happenstance, and The Republic of Love. Her books have won a Canada Council Major Award, National Magazine Awards, the Canadian Author’s Award, and a CBC short story award. In 1995, Shields received the Pulitzer Prize for The Stone Diaries. The Stone Diaries also won the National Book Critics’ Circle Award, Canada’s Governor General Award, was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, and was named a Notable Book by The New York Times Book Review and one of the best books of the year by Publishers Weekly. Most recently, Shields received the United Kingdom’s Orange Prize for Fiction forLarry’s Party

PRAISE

“Beguiling…a work of radiance…Larry’s Party confirms Shields’s preeminent position among contemporary novelists.” —The Philadelphia Inquirer

“Using her fierce gift for observation, a natural storytelling talent and a gently comic charm, [Shields] gives us a nicely tactile sense of Larry’s ordinary life.” —The New York Times

“Shields captures an unremarkable man in a remarkable light.” —Time

“[Shields] has a knack for turning the ordinary into the extraordinary….Arrestingly real.” —New York Daily News

“Larry’s Party showcases the elegant phrasing and evocative imagery that render her work a rare treat.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“Triumphant.” —Publishers Weekly

RELATED TITLES

Happenstance

0-14-017951-8

The Stone Diaries

0-14-023313-X

Small Ceremonies

0-14-025145-6

The Republic of Love

0-14-014990-2

The Box Garden

0-14-025136-7

Swann

0-14-013429-8

Various Miracles

0-14-011837-3

The Orange Fish

0-14-015282-2

A CONVERSATION WITH CAROL SHIELDS

Many people have called Larry Weller the “male counterpart” to Daisy Goodwill, the character in The Stone Diaries. Is that what you were trying to accomplish? Did you think about Daisy at all when you were writing about Larry?

I don’t think of Larry as a male counterpart to Daisy Goodwill. The book seemed to me a separate endeavor. For one thing, [Larry’s Party] surveys a slice of a life, not a whole life. I chose to look at Larry between the ages of 27 and 47, since it is during this period, I think, that most of our life choices are made. My idea was to lead him to “the center of the maze,” a resting place in his life, but not the final resting place. Of course, I thought of Daisy as I wrote about this very ordinary man. It seems I am always thinking about gender and how the “accident” of gender alters our behavior and our expectations.

I’ve read you believe that coincidences are at the heart of what makes the universe go round. With Larry’s Party, did you set out to write a novel that brought this theory into focus? Has coincidence played a significant part in your own life?

I am deeply interested in synchronicity and, in fact, all forms of coincidence. In Larry’s life, accident plays a major role, and he is the sort of person who allows this to happen. He is, in a sense, someone who lets life happen to him, but then I believe most of us fall into that particular camp. I’ve heard people say that we write our own script, but I’ve never been able to believe it. The forces of the world are too many and too complex to permit us this privilege. I suppose my life is as full of historical accident as anyone else’s. I was born in the depression, spent a wartime childhood, married in the fifties. All these kinds of things must color in the squares of an individual life.

Why did you write Larry’s Party in the third person, and not first person?

Except for my first two novels (Small Ceremonies and The Box Garden), I’ve mostly written in the third person. Each position permits a writer certain liberties and imposes a balancing set of restrictions, but I find more and more that third person allows me to enter the narratives of people whose lives are very different from my own.

Language and communication are tremendously important to Larry. In fact, he all but says that his lack of vocabulary was a key factor in the breakup of his first marriage. Does a large, articulate vocabulary heighten the experiences of life? What about unspoken or unwritten communication?

I’ve always sensed that language is the great liberator. The fitting phrase, the precise word—these permit us to be more nearly ourselves. Like everyone else, though, I sometimes fear there is too much language pouring down on us, an overdose of communication that deadens us to private reflection.

Are there times that you find yourself struggling to articulate a particular sensation or feeling? Do you think that there is a word for every stop on the entire spectrum of human emotion?

I struggle all the time, and have come to understand that certain human responses leak around the edges of language. Larry Weller knows this too, when he wonders whether language has evolved to the point where it can be fully expressive. I suppose writers use the nuances of tone when language itself fails us, or the useful tricks of metaphor.

How did the narrative order of Larry’s Party unfold? Did you know from the beginning that his journey through life would be a circular one?

I love to create structures for novels, and I very early saw a double structure in Larry’s Party. There was the ongoing chronological framework, in which I cut into his life every year or two to see what was going on. And then there was what I call a CAT scan structure in which I slice transversely into an aspect of his life—his folks, his work, his friends. This second structure was particularly useful to me since I was struck by the fact that men, on the whole, tend to compartmentalize their lives more than most women do.

You’ve said, “I’ve learnt that men don’t often ask questions; women ask questions and men supply information.” InLarry’s Party, Larry seems to be asking the questions, while the women he surrounds himself with answer them. Is Larry an exceptional case or are you making more general claims about male/female relationships?

Perhaps Larry is more searching than most men. Certainly he asks the major existential questions: How did I get here? Is this all there is? But I’m not sure he asks the smaller and necessary questions. He doesn’t probe his mother’s religious impulses, nor ask his sister if she is happy. And he scarcely communicates with the young Dorrie at all.

How different do you think the men and women coming of age today are from those that grew up in the fifties? Do you think that our roles in relationships are “wired” in such a way that no matter what generation, certain elements of our relationships will ultimately remain the same? Do you believe that men and women are “wired” differently?

We went through an interesting period in the seventies when we optimistically believed that given the same kind of conditioning, men and women would grow increasingly alike in their personalities. This seems not to have happened; I can only suppose that our differences are Darwinian in nature and that they are likely to remain differences. The best we can do, perhaps, is modify extremes and cultivate sensitivity.

Your previous novel, The Stone Diaries, won the Pulitzer prize. Did you feel exceptionally pressured to write a book that would match your prior success?

Oddly, I felt no pressure at all after winning the Pulitzer. Certainly I was not badgered by my publishers. I’ve never believed that writers must “top” themselves with each new book. A creative life doesn’t work that way, thank heavens. Most of us write out of where we are at the moment and we write the very best book we’re capable of.

You’ve written a novel about the typical twentieth-century woman, Daisy Goodwill. You’ve written a novel about the typical twentieth-century man, Larry Weller. What is next?

I suppose I’ll continue to write about certain unresolved questions: the question of art and who makes it, the problems and puzzles of gender, and the arc of a human life which is, in the end, the only plot that interests me.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS