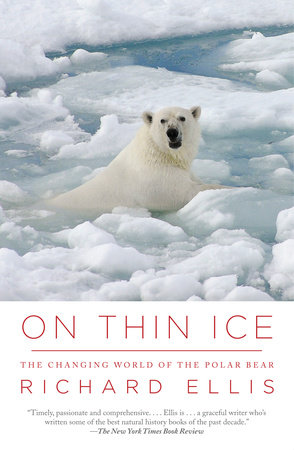

Q: First things first, why polar bears?

A: Polar bears are probably the most charismatic mammals on earth. They are beautiful, powerful, popular, misunderstood–and seriously endangered. After all the other books I’ve written, this seems like the book I was born to write.

Q: You begin the book with your own intimate encounter with a polar bear at the North Pole in 1994. Can you describe what brought you there, and why this encounter was so remarkable?

A: As a lecturer on Arctic wildlife, I was leading a cruise to the North Pole for the American Museum of Natural History (New York). We were on a Russian icebreaker, north of Spitsbergen, when we spotted this bear right alongside the boat. I photographed it (from the deck of the ship) until I ran out of film. (That was 1994, back in the days of film cameras.) At that time, the North Pole was covered with ice, about 8 feet thick. Within a few years, however, the Arctic ice cap had begun to melt, and ships arriving at the Pole found only open water. For me, the bear and the thick ice (the Russian sailors chopped a hole in the ice and we went for a dip at the North Pole) clearly showed the Arctic as it was 15 years ago–and will never be the same again.

Q: What in your opinion is the biggest misconception about polar bears?

A: People think of polar bears as man-eaters, always ready to attack (and eat) people they encounter on the ice. Nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, polar bears are intensely curious about anything that appears in their otherwise desolate landscape, and will approach and investigate sleds, tents, ships, people, dogs and anything else that looks unusual to them. Unfortunately for the bears, their curiosity is easily mistaken for aggression–if a bear pokes its head inside your tent, you might not want to wait to see what it had in mind–so bears have almost always been approached with a “shoot first, ask questions later” attitude. Yes, there have been polar bear attacks on people, but people attacks on bears probably outnumber them 1,000 to one.

Q: Unlike some other books on polar bears you trace man’s history with the bear back to the 16th century. What were these early encounters like?

A: When the first explorers and whalers headed north, they encountered all sorts of unexpected animals, including bowhead whales (the object of the Greenland “fishery”), narwhals, belugas, and of course, the stately, white, ghostlike bears. People almost always shot the bears they saw, often because they felt threatened (see above), but also for target practice. A big beautiful animal standing on the ice was too good an opportunity to pass up.

Q: What is it about its whiteness that has made the polar bear such an iconic (and sometimes feared) creature?

A: First of all, a white bear is most unusual, as all other bear species are brown or black. For its own reasons, polar bears blend into their environment, but people saw this as a device for sneaking up on them. White is usually considered the color of cleanliness, goodness and purity, but no less an authority on that color (or lack thereof) than Herman Melville wrote, “This elusive quality it is, which causes the thought of whiteness, when divorced from more kindly associations, and coupled with any object terrible in itself, to heighten that terror to the furthest bounds. Witness the white bear of the poles, and the white shark of the tropics; what but their smooth, flaky whiteness makes them the transcendent horrors that they are? That ghastly whiteness it is which imparts an abhorrent mildness, even more loathsome than terrific, to the dumb-gloating of their aspect. So that not the fierce fanged tiger in his heraldic coat can so stagger courage as the white shrouded bear or shark.”

Q: The polar bear has become a media star in recent years, both as the poster child for global warming and as cute cubs (like Knut) are born in zoos around the world. Their political significance has increased greatly and you compare this to the profile of whales during the 1980s. Has this increased attention been making a difference?

A: The polar bear has become a sort of double-barreled icon: On one hand, its cuteness has endowed with the kind of popularity in zoos, TV shows, and advertising that is unequalled by any other creature (except perhaps penguins, which are not nearly so cuddly); and on the other, the lone bear, traversing the endless icy wastelands in search of food or a mate has come to symbolize the precarious state of the Arctic itself. But too many people are more concerned with oil and gas prospecting in the Arctic, and they will not let the bears–no matter how cute or endangered–stand in their way.

Q: A frequent image invoked by environmental and conservation groups is that as the ice flows melt, polar bears are forced to keep swimming in search of ice until they drown. How widespread is this awful fate?

A: It is probably true that some bears set out to swim in search of ice floes that are not there, and even though these marine bears can swim for 100 miles, some of them keep swimming until they drown. But more critical is the loss of the ice itself, the required habitat for breeding seals. As the ice continues to recede, the seals will have no place to deliver their pups, and no seal pups means no food for the bears. As polar bears eat ONLY seals (and an occasional walrus), if their main prey items disappear, the bears will too.

Q: There are polar bears in zoos around the world, even right in the middle of Central Park. How are the arctic creatures able to survive in these climates?

A: In fact, polar bears don’t do very well in zoos. Because of their enormous range (some bears can cover 100,000 miles in their lifetimes), confinement in a small enclosure, even one with rocks and a pool, is completely antithetical to their lifestyle. They survive in zoos all right, but they often exhibit repetitive behavior, like swimming or walking around in endless circles, or in some cases, attacking people. (There have been two fatal polar bear attacks in New York City zoos.)

Q: Your last chapter is titled “Is the Polar Bear Doomed?” In your opinion, is the polar bear doomed, or are there still steps that we can take to save bears and their habitat?

A: The polar bear can be saved by reducing greenhouse gases to curtail global warming. Some scientists believe that we have already reached the tipping point, and even if we were to reduce carbon dioxide emissions to zero TOMORROW–which seems somewhat unlikely–the Arctic ice would continue to melt at an increasingly accelerated rate. As it melts, more sunlight hits the water, which means more warmer water, which means more ice melting.

Because polar bears have evolved in a very specialized environment–the ice and waters of the Arctic–they cannot easily adapt to another way of life. Some polar bears have wandered south in search of food, and have found themselves so far from their natural food supply that they starved to death. Can’t we simply move them to the Antarctic where there is still plenty of ice and plenty of penguins to eat? In a word: NO. They would be as out of place on the Antarctic ice sheet as they would be in the rain forest. Antarctic seals some of which are almost as big and aggressive as polar bears do not den under the ice, and the bears could not possibly catch them in the water. If they were to feed on penguins, which they certainly could catch (and also feed on the eggs and chicks), they would quickly endanger the various penguin species, some of which are in trouble already. Finally, the seasons in the Southern Hemisphere are the reverse of those in the north, so transplanted bears would be completely turned around, with their denning and hunting seasons reversed.

Transplanting animals, for whatever reason, is a terrible idea. Think of what happened when they introduced rabbits into Australia, or mongooses into Hawaii (instead of eating the rats, they ate the birds). The Everglades now has a serious python problem, from the giant snakes that their owners couldn’t handle and released into the swamp. Recently, a python in Florida killed a two-year-old girl and tried to swallow her.

Q: You have now written books about sharks, whales, squid, tuna, and now polar bears. Is there a species that you’ll be writing about next?

A: I’m working on a study of the sperm whale, unquestionably the weirdest animal on earth (and of, course, the subject of Moby-Dick.) From its 20-foot- long nose, in which there is a complex of tubes, sacs and lips (yes, lips in its nose), and thousand gallons of clear oil, the sperm whale can broadcast–and aim–sonic bursts that are the loudest sounds made by any living creature, louder than a spaceship takeoff. They use these sound bursts to immobilize and kill their prey (sometimes giant squid) a mile down. And the whale can hold its breath for an hour while doing it. Amazing!