-

$23.00

Aug 21, 2012 | ISBN 9780307356451

-

Sep 27, 2011 | ISBN 9780307366870

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Born on a Mountaintop

Extraordinary Canadians: Louis Hippolyte Lafontaine and Robert Baldwin

The Long Way Home

Northern Light

The Rough Riders

Mexican Days

American Legend

The Tin Ticket

Praise

WINNER 2012 – Writers’ Trust of Canada Shaughnessy Cohen Prize for Political Writing

WINNER 2012 – Dafoe Book Prize

FINALIST 2011 – Charles Taylor Prize for Literary Non-Fiction

FINALIST 2011 – BC National Award for Canadian Non-Fiction

FINALIST 2011 – Governor General’s Literary Award for Non-Fiction

FINALIST 2011 – Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize for Non-Fiction

A Globe and Mail Best Book

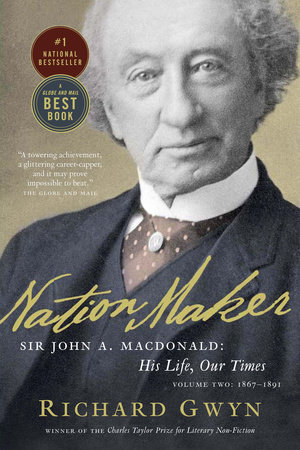

“Gwyn…has given us a first prime minister for the 21st century…. The book is a towering achievement, a glittering career-capper, and it may prove impossible to beat.” The Globe and Mail

“Writing with his usual elegance and insight, Richard Gwyn has done full justice to the man whose own story is inextricably interwoven with that of Canada.” Margaret MacMillan, author of Paris 1919

Awards

Dafoe Book Prize WINNER 2012

Shaughnessy Cohen Award for Political Writing WINNER 2012

Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Non-Fiction Prize NOMINEE 2011

British Columbia’s National Award for Canadian Non-Fiction FINALIST 2011

Charles Taylor Prize for Literary Non-Fiction FINALIST 2012

Governor General’s Literary Award – Nonfiction FINALIST 2011

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In