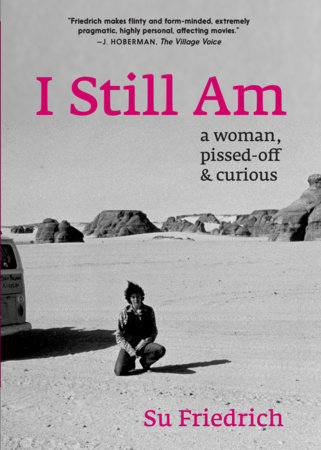

“A young lesbian feminist’s casually daring, low-budget trip through Africa in the mid 1970s—that set an impressive filmmaking career on its path—has given birth decades later to a unique book, an eccentric collage of stunning photographs and detailed accounts of places, friends, encounters, and challenges. I Still Am… is honest, unembellished, empathetic, and impossible to summarize.”

—Lucy R. Lippard

“Su Friedrich’s travel memoir is delightedly funky and readable. It’s a book to hang out with, savoring the materiality of analog time and its very real subject which is Africa in 1976 and how a young queer newly torn away from the cocoon of privilege and lavender collectives made common cause with young Black mothers bursting with muscles and baskets and babies who lightly welcome her into a fragile patch of shared time. I Still Am is a high-risk act of political seeing and being seen and one that manages to come home with a trunkful of memories, vulnerable and frankly shared.” —Eileen Myles

“I Still Am is a portrait of the artist as a young woman. It’s an expansive, raw, and intimate narrative. Deliciously illustrated with compelling photographs, Su never holds back.”

—Accra Shepp

“Su Friedrich’s 21-year-old precocious introspections make this whole book fascinating, including how she dealt with so many different social and economic conditions. A great read.”

—Yvonne Rainer

“Filmmaker Friedrich recalls traveling across post-colonial West Africa in 1976, when she was 21, in this intriguing if somewhat overwhelming account. Less a linear narrative than a scrapbook of journal entries and photos, the book traces Friedrich’s travels alongside her political musings. She’s sharply attentive to gendered power dynamics, particularly in her encounters with Nigerian women, registering both solidarity and the vast distance between their lives. Her commentary on patriarchy, race, and class often feels strikingly contemporary, though it’s rooted in the social tensions of the 1970s. She can be biting (“If the country is ‘being brought into the modern world,’ it usually means that the wife of the President has a microwave oven & that the facilities for tourists are improving”), but moments of political rupture, including the assassination of Nigerian president Murtala Ramat Muhammed, prompt sober reflections on U.S. influence abroad. The sheer volume of material, coupled with frequent changes of location and a lack of recurring figures, can be disorienting. Still, Friedrich’s striking black-and-white photographs—of people, townscapes, and art—help paper over some of the confusion. Clear-eyed and unsentimental, this succeeds as a self-aware meditation on the difficulty of telling complex truths.

—Publishers Weekly