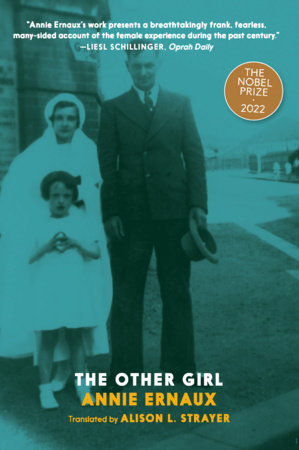

*”In this gently heartbreaking account, Nobel Prize winner Ernaux (The Use of Photography) reflects on the death of her older sister, Ginette, in 1938, two years before the author was born. Months before the diphtheria vaccine was made compulsory in France, six-year-old Ginette died of the disease. Taking inspiration from Franz Kafka’s Letter to His Father, Ernaux addresses her late sibling directly, compiling all she knows of Ginette’s life, death, and legacy into a diaristic dossier. Though Ernaux’s parents never spoke of Ginette, the author tracks down and interviews the few living people who remember the girl’s death, seeking to map the devastation it wrought on her family before Ernaux was born. Elsewhere, she recalls hearing adults call Ginette a “nice” girl and Ernaux a “demon,” which saddled her with lifelong feelings of inadequacy, and makes a number of poignant literary allusions, comparing her late sister to Peter Pan and Jane Eyre’s tuberculosis-stricken Helen Burns. Poetic and raw but never maudlin, this beautiful meditation on a very particular kind of grief will resonate with anyone trying to process a major loss of their own.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“Originally published as part of a French series inviting authors to compose ‘the letter they’d never written’—after Franz Kafka’s letter to his late father…. Ernaux is 10 when she overhears her mother talking about another daughter, one who died at 6 of diphtheria…. No matter how slim, though, Ernaux’s books are not chapters, but volumes; bundling them as a single story ignores the texture of recurrence…. One pivotal, painful memory at a time, Ernaux evaluates her life. A central question: Why would she, a country girl with grandparents who never learned to read, choose to write? In book after book, there is another stab at an answer…. The book’s ghostly subject and epistolary form provide Ernaux with yet another origin story…. Economically and poetically, Ernaux traces not only the discovery of this bizarre secret, but the ways in which knowing and not speaking it (never once, to either of her parents) has impacted her, universalizing the emotion of something incredibly specific.” —Natasha Stagg, New York Times Book Review