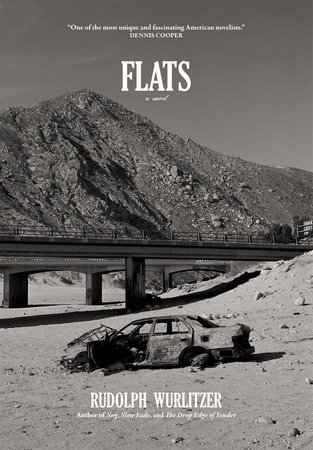

“Each book is short, but dense and trippy. If you want to know what it felt like to be a reader in the late ’60s and early ’70s, when so many new experimental works were put out by mainstream publishers, these books are great places to start. Nog even had a blurb from Thomas Pynchon (“the novel of bullshit is dead!”), Flats wore its Samuel Beckett influence proudly on its sleeve, Quake took us through a slo mo pomo earthquake in L.A. Together they provide a tour of the dissolution of identity that was daily life in the late sixties.”

—Michael Silverblatt, KCRW’s Bookworm

“Reading Rudolph Wurlitzer’s novels is like watching a road movie backward. In his 1969 underground classic, Nog, the narrator drifts across an amorphous terrain on which his shifting identity molds itself like soft clay. Flats and Quake mine much the same territory, a post-cataclysmic landscape in which heroic storytelling has been blown to bits. Quake reads like a mash-up of On the Road and Waiting for Godot. For the first time in more than three decades, it’s possible to investigate the interplay between Wurlitzer’s novels and his screenplays, the way his radical experiments in one informed his canny deconstruction of the other.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Push aside Brautigan and Ginsberg and make room in the curriculum for Wurlitzer as an overlooked and undervalued voice of the counterculture of the ’60s and ’70s, wedged comfortably between the collected works of Willam S. Burroughs and Hunter S. Thompson.”

—Rodger Jacobs, PopMatters

“The reader, the writer, and the denizens of [Flats] all get taken for a ride here, then are set down, slightly more cracked than they were before. [Quake] is Wurlitzer at his most Pynchonian. The frontier—alluded to in Flats, deconstructed in Wurlitzer’s 1973 screenplay for Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, and played for laughs in last year’s Drop Edge of Yonder—is again the subject [in Quake], posited this time as the place where humans turn back into whatever they turn back into when the marijuana and Social Security run out.”

—Village Voice