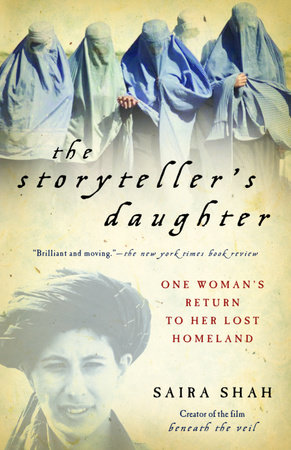

Author Q&A

A Conversation with Saira Shah

Q: Tell us about your father, the writer Idries Shah, and his influence upon you to become a storyteller yourself.

A: My father was a writer and thinker, who happened to be a Sufi. Part of his work dealt with making traditional Eastern stories accessible to the West. Stories were a part of my childhood–and never considered just for children. This was a family tradition and a very Afghan one. Nobody apologized for telling stories–even now my father is dead, my aunt continues the same way–you can be talking to her about her chilblains, and the next minute she will be telling you a fairy tale, say, or an anecdote about the tenth century Afghan king Mahmud of Ghazna.

Q: Talk about what it was like to grow up as an Afgan-in-exile in Britain.

A: We weren’t exactly exiles–a return trip seemed to be always around the corner–until the Soviet Union invaded in 1979, when I was 15. I grew up with two self-contained worlds, which rarely met–my sedate middle class existence in Kent, and a sort of virtual homeland, woven from stories.

Q: Why did you become a journalist?

A: I wanted to travel to Afghanistan, and the country was at war. I also felt (but didn’t really realize it at the time) a need to reconcile my Eastern–myth-making–side with my Western love of factual truth. I told myself I wanted to uncover the truth behind the myth–but probably, more likely, I wanted to discover that the myth WAS literal truth.

Q: Please talk about your search for personal and cultural identity. How have the facts informed you? How about the ancestral myth that has been your inheritance? Which gets you closer to truth–fact or mythology?

A: A lot of the book deals with the question of how to approach truth. There is a Persian

saying: ‘the question about the sky, the answer about a rope’. Facts try to build a ladder, rung by rung, to approach the sky, while stories and myths try to provide an overarching rainbow of metaphor, which can give you a taste of what the sky is like, though not necessarily physically reach it! In my quest for Afghanistan, I used both. Both were helpful–and I suppose you could argue that neither could be really useful without the other.

Q: Your film "Beneath the Veil" was widely viewed and had tremendous impact on the world’s understanding of what was going on in Afghanistan in the lives of women. How do you feel about your role in telling this story?

A: I was, and am, very proud of how the film turned out. It was teamwork–between me, the director Cassian Harrison, and the cameraman on that project (later to become an Emmy-winning director) James Miller. The timing was astounding–and not always to the good. If we had known that September 11th was going to happen, followed by a US-led bombardment of Afghanistan, we would have done some things in the film very differently.

Q: How did the culture of the Taliban come to take over Afghanistan–a country that had a cultural elite and that educated its women? Where does that conservative impulse come from?

A: The cultural elite was miniscule. Women educated only in towns. The Taliban–as has been very well documented–are a hybrid of impulses: Pushtun tribal values, conservative village mullahs with a very narrow view of Islam and the West (one once told me that in the West women are allowed to marry dogs), an influx of mainly-wahhabi Muslims (known as Arabs) who came to fight alongside the mujahidin against the Soviet Union.

Q: Talk about the difference between film making and writing a book. Which medium do you prefer for telling a story?

A: I’ve loved writing, although I found it difficult. It seemed like it was the thing I should always have been doing. You can be much subtler in a book, explore many more ideas. TV is a linear medium. I’d like to write novels.

Q: Do you think things have changed in Afghanistan since the most recent war?

A: Of course they’ve changed–nothing stays still. But there are still overwhelming problems. The main one, I think, being that the West picked the wrong problem to solve–getting rid of the Taliban and chasing Osama. There needs to be much more emphasis from the West on rebuilding Afghanistan, rather than destroying perceived enemies. That will take at least a generation and require cash and care.

Q: Do you think Osama Bin Laden is alive or dead?

A: I have no clue–and I think Osama Bin Laden is a huge red herring. The West needs to concentrate on the factors which created Osama and helped him to flourish, not on the man himself. There can be any number of Osamas.

Q: How often do you get to Afghanistan these days? When were you last there?

A: I was last there in October 2001–at the ending of the book. I was supposed to go this spring, but the tragic death of my friend and business partner James Miller made it impossible. I hope to go and spend proper time there when I have finished the film I was working on with James.

In the meantime, I am campaigning for Israel to hold a proper, independent and open

investigation into how he was killed.

Q: Please talk about your most recent project–the film you made in Israel.

A: It was a film for Home Box Office about the impact of violence on children in the Gaza strip. I am interested in the concept of things, which appear to be in opposition, actually having the effect of working together–and in Gaza, you can see how violence on both the Israeli and Palestinian sides drive these kids in the same direction–further militancy, desire for martyrdom, a culture of despair.

Q: You’ve often covered the world’s hot spots–Kosovo, Northern Ireland, Africa, etc. Why do you think you are drawn to these places?

A: I’m not. Ninety per cent of my war experience was Afghanistan. The rest I have done as part of being a professional news reporter, or else for a specific project. I’m not drawn to war at all. I am drawn to places where you can witness human beings living in extremities of various kinds. Then you see the full gamut of which humans are capable–their capacity for good and evil, dignity and horror.