READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION TO THE WELL OF LOST PLOTS

Thursday and her pet dodo, Pickwick, have taken up temporary residency in a run-of-the-mill unpublished crime novel called Caversham Heights through the book world’s Character Exchange Program—at least for the duration of her pregnancy. While the pages of an obscure, unpublished novel seem like a safe harbor, Thursday’s enemy stalks her in her sleep. Aornis uses her skills as a mnemonomorph to alter and destroy Thursday’s memories, which are all she has left of her eradicated husband. Granny Next, apparently an ex-Jurisfiction operative herself, unexpectedly appears on Thursday’s doorstep to try to help her battle the mindworm, but Thursday must face off with Aornis, and her darkest nightmares, alone.

It seems that no one in the book world is safe anymore. Thursday reports for duty with her Jurisfiction colleagues at their headquarters in the Dashwoods’ ballroom in Sense and Sensibility to discuss UltraWord™, the Book Operating System upgrade that has the entire fiction world buzzing with anticipation. But when the squad heads out to chase down the escaped Minotaur, Agent Perkins’s body is found mangled at the Minotaur’s vault, and Agent Snell dies from contact with the deadly “mispeling vyrus.” While Snell’s and Perkins’s deaths in the line of duty at first seem legitimate, a missing vault key, a damaged Eject-o-Hat, and Snell’s horribly misspelled final words point to sabotage. But at the 923rd annual BookWorld Awards, Thursday alone can stop a conversion of power that will shake the world of fiction to its very core.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

The Well of Lost Plots

- Do you think the UltraWord™ plot is a parable about television’s effect on the imagination? What similarities or differences do the two have?

- Who is the Great Panjandrum? What is her role in the book world?

- Miss Havisham gives Thursday a piece of the “Last Original Idea . . . a small shard from when the whole was cleaved in 1884.” Do you think the last original idea has been thought and dispersed already? Why or why not?

- The Jurisfiction characters argue about the “basic eight-plot architecture we inherited from OralTrad.” Do you think it’s true that “No one will ever need more than eight plots?” If Coming of Age, Bitter Rivalry/Revenge, and Journey of Discovery are part of the eight-plot architecture, what do you think the remaining five plots are? Which would The Well of Lost Plots come under?

- Thursday sees her worst nightmare when she gazes in the mirror that Aornis holds up to her in her dreams, but it is not the memory of her brother Anton’s death. What is it that Thursday sees in the mirror? What images might you see in the mirror? What is the significance of the “lighthouse” at the edge of her mind?

- When Snell tells Thursday that Landen can be written into fictional existence so they can live together in the book world, Thursday replies that she wants the real Landen or none at all. Are memory and imagination powerful enough to sustain a real person? If everything in the book world seems real enough, why would Thursday not choose the written Landen? Would you revive people you have lost in your life if you could? Why or why not?

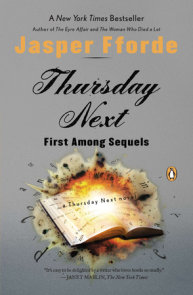

ABOUT JASPER FFORDE

Jasper Fforde is the author of The Eyre Affair, Lost in a Good Book, (both from Penguin) and The Well of Lost Plots (Viking), the first three books in the Thursday Next fantasy/detective series. He lives in Wales

AN INTERVIEW WITH JASPER FFORDE

Thursday Next seems to be descended from a long line of British crime stoppers like Sherlock Holmes and James Bond, and her name is a clear homage to G. K. Chesterton’s classic The Man Who Was Thursday. Who are your favorite fictional detectives and how, if at all, did they shape Thursday Next?

Actually, the name wasn’t drawn from Chesterton at all; neither, as a reader suggested, from Paris’s line in Romeo and Juliet:

Paris: What may be must be this Thursday next.

Juliet: What must be must be.

Friar Lawrence: Now there’s a certain text.

Much as I would like to claim either as the truth, sadly not. The real influence was much closer to home and infinitely more mundane. My mother used to refer to days in the future in this manner: “Wednesday week, Tuesday next,” etc., and I just liked the “tum-te-tum” internal rhythm of “Thursday Next.” It intrigued me, too. What kind of woman would have a name like this? I’m not sure which detective Thursday is drawn from—perhaps all of them. My favorite detective was always Miss Marple, and perhaps Thursday has Jane’s strict adherence to duty and the truth. There is undeniably a bit of James Bond, Sam Spade, and Richard Hannay about her, although as character models I have always drawn on women aviators from the golden age of aviation, as these extraordinary characters (Bennett, Earhart, Markham, Coleman, Johnson) had not just a great passion and zest for life and adventure but also an overriding sense of purpose. In a word, Spirit.

You worked in the film industry for nineteen years before becoming a full-time writer. In our society, film is a more popular and lucrative medium than books, but in Thursday’s world, the novel is king. Having had a finger in each pie, would you prefer to live in Thursday’s world or ours? Did your work in film affect the narrative of the novel?

I think I’d prefer to live in Thursday’s world—and I do, six months a year when I’m writing the books. Mind you, if I were a writer in Thursday’s world I’d be writing about a heroine who doesn’t do extraordinary things at all and lives in a UK where not much happens. And when I was asked in THAT world which world I’d prefer to be in, I’d say… Oh, lawks, we’ve entered a sort of Nextian “closed-loop perpetual opposing answer paradox.” Better go to the next question. Yes, film did most definitely affect the narrative. Because I have been educated in film grammar, I tend to see the books as visual stories first and foremost, and describe the story as I see it unfolding. That isn’t to say I don’t play a lot with book grammar, too, but I can’t shrug off my visual origins. Mind you, I would contend that reading is a far more visual medium than film, as the readers have to generate all of the images themselves; all I do is offer up a few mnemonic signposts. I am always astounded by the number of readers who can describe the Nextian world in profound detail—perhaps this is the reason why movies-from-books tend to be such a huge disappointment.

What are your favorite classic novels?

Jane Eyre was probably my favorite of that type of “literary” classic. Dickens is great fun, too, although to be honest I still prefer Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland for its high-quality nonsense virtuosity and Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat for its warmth, observation, and humor. Both were written in Victorian times and are classics—just a different sort. Swift’s Gulliver’s Travelsis another firm favorite, as is Grossmith’s Diary of a Nobody.

Why did you choose Jane Eyre for Thursday’s first jump into literature?

Three reasons. First, it’s a great book. The characters of Jane Eyre, Rochester, Mrs. Fairfax, Grace Poole, Bertha, and Pilot the dog are all great fun to subvert in the name of Nextian entertainment. Second, it is well known, even 150 years after publication. For The Eyre Affair to have any resonance the featured novel had to be familiar and respected. If potential readers of my book haven’t read Jane Eyre they might have seen the film, and if they haven’t done either, they might still know that Jane is a heroine of Victorian romantic fiction. I don’t know of many other books that can do this. Third, it’s in the public domain. I could do pretty much what I want and not have to worry about copyright problems—given the premise of the novel, something that had to remain a consideration!

Your novels have been described as a sort of Harry Potter series for adults. Why do you think fantasy and magic tales are enjoying so much popularity right now? Why do adults find the stories so satisfying?

I’m not really sure why fantasy is popular right now, but the tastes and moods of the book-reading public do tend to move around, so in a few years we might all be reading “Squid Action/Adventure” or “Western Accountancy,” so who knows. Mind you, I’ve never been one to make such a huge distinction between children and adults—I have remained consistently suspicious of people who describe themselves as “adults” from a very early age. We all enjoy stories—it is a linking factor between all humans everywhere, that strange and uncontrollable urge to ask, “Yes, but what happens next?” Perhaps fantasy offers imaginative escapism more than other genres. I was very happy when I learned that Harry Potter was being sold in “plain covers” in the UK so adults could read it on the train without feeling embarrassed. “Ah,” thinks I, “there is hope yet!”

The Tie-seller in Victoria says, “There are two schools of thought about the resilience of time. The first is that time is highly volatile, with every small event altering the possible outcome of the earth’s future. The other view is that time is rigid, and no matter how hard you try, it will always spring back toward a determined present.” Which do you think is more likely?

From a narrative point of view, the notion of time somehow wanting to keep on a predetermined course is far preferable. It makes the ChronoGuard’s job that much harder. It’s not easy to change things, as Colonel Next often finds out. Personally, I think time is highly volatile—and out there for us to change, if we so wish it. Most of the time we don’t. Our notions of self-determination are, on the whole, something of a myth. We are governed almost exclusively by our own peculiar habits, which makes those who rail against them that much more remarkable.

If time travel were a reality, do you think it would be possible for people to visit other eras responsibly?

Of course not! When have humans ever behaved responsibly? That’s not to say I wouldn’t be first in the queue, but mankind is far too flawed to resist wanting to use this new technology to deal with other problems, such as radioactive waste disposal or something. Given mankind’s record so far, it wouldn’t be long before the criminal gangs moved in to steal items from the past to sell in the future. The ChronoGuard refer to this sort of crime as “Retrosnatch,” although the upside of this is that you can always catch the person red-handed after the event. Before the event. During the event.

If you could travel in time, when would you want to visit and why?

Good question! The choice is endless. Since I’m a fan of nineteenth-century history, one of the times I would visit would be during a conversation that took place between Nelson and Wellington in September 1805. It was the only time these two historical giants met. Failing that, the day Isambard Kingdom Brunel launched his gargantuan steamship the Great Eastern into the Thames or, further back still, 65 million years ago when an asteroid hit the earth—must have been quite a light show. Closer to home, I suppose I’d like to revisit the first time I learned to ride a bicycle without stabilizers—a more joyous feeling of fulfillment, freedom, and attainment could only be equaled by the time one learns to walk or read.

Acheron Hades may be the third most evil man on earth, but he’s also a charming, seductive adversary with some of the best lines in the book. If Acheron Hades is only the third most evil man on earth, who are second and first, and will Thursday get to face them?

The “third most evil man” device was to hint at a far bigger world beyond the covers of the book. Since I made this rash claim many people have asked the same question, and I can reveal that the Hades family comprises five boys—Acheron, Styx, Phlegethon, Cocytus, and Lethe—and the only girl, Aornis. Described once by Vlad the Impaler as “unspeakably repellent,” the Hades family drew strength from deviancy and committing every sort of debased horror that they could—some with panache, some with halfhearted seriousness, others with a sort of relaxed insouciance about the whole thing. Lethe, the “white sheep” of the family, was hardly cruel at all—but the others more than made up for him.

Acheron Hades isn’t the only personification of evil in your novels. Just as evil, and much more insidious, is the English government’s indentured servitude to the Goliath Corporation and Goliath’s willingness to sacrifice human lives for wartime financial gain. Why did you choose a corporation as the other major villain in the story? Do you think a relationship like the one between England’s government and the Goliath Corporation could exist in real life?

I like the Orwellian feel of Goliath—oppressive and menacing in the background. As a satirical tool, its use is boundless. I can highlight the daftness of corporations and governments quite easily within its boundaries. Goliath is insidious, but what I like about it most is that it is entirely shameless in what it does—and that no one in Thursday’s world (except perhaps Thursday herself) seems to think there is anything wrong with it. Perhaps the fun with Goliath is not just about corporations per se, but how we react to them.

The Eyre Affair, Lost in a Good Book, and The Well of Lost Plots have all been great successes, and I’m sure your fans will make a success of their follow-up, Something Rotten. If you could retire now and live in any book, which book would you like to spend the rest of your days living in?

An all-book pass to the P. G. Wodehouse series would be admirable. Afternoon teas, a succession of dotty aunts, impostors at Blandings Castle—what could be better or more amusing?