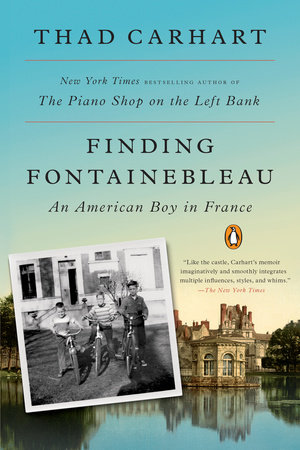

Finding Fontainebleau

By Thad Carhart

By Thad Carhart

By Thad Carhart

By Thad Carhart

Category: Biography & Memoir | Travel: Europe | Parenting

Category: Biography & Memoir | Travel: Europe | Parenting

-

$17.00

May 16, 2017 | ISBN 9780143109280

-

May 17, 2016 | ISBN 9780698191617

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Wickett’s Remedy

Good Things Out of Nazareth

Bobbed Hair and Bathtub Gin

The Unfinished Novel and Other Stories

Old Books, Rare Friends

Wild Gratitude

Morality for Beautiful Girls

Katerina

A Dog’s Life

Praise

“While bringing alive this redolent Gallic chapter of his boyhood (baguettes from the boulangerie; inkwells and laborious handwriting exercises at school), Mr. Carhart also resurrects the mood and mores of a particular window in time: the 1950s of Ike and Elvis’s America, and postwar France. . . . Like the castle, his memoir imaginatively and smoothly integrates multiple influences, styles and whims.”—The New York Times

“A lovely snapshot of daily life in a bygone France, as well as a tribute to the artistic and architectural glories of this centuries-old royal palace, a predecessor to Versailles.”—Newsday

“Perfect . . . [A] giant jigsaw puzzle of history, reminiscence and anthropological detail which paint a complicated but indelible picture…. Details, impressions, memories—and what the author does with them—are the heart and soul of this lovely book.”—The Washington Times

“A vivid picture of the rhythms and flavor of post-war France.”—Northampton Daily Hampshire Gazette

“Carhart turns his observant eye on small, sometimes odd-seeming details—the once-ubiquitous Turkish toilets in cafes, the uniquely French method of taking household inventory, French cars of the 1950s. These lovely digressions, along with Carhart’s own family’s story, illuminate French culture in an appealing way.”—BookPage

“American casualness and exuberance meet French formality and grandeur in this lively, perceptive memoir.”—Publishers Weekly

“The author of The Piano Shop on the Left Bank (2001) returns with another celebration of France…Those lucky enough to have lived and attended school in Europe will love this book, and anyone heading to Paris will surely add Fontainebleau to his or her schedule.”—Kirkus Reviews

“Part memoir, part history, part love letter to France—Thad Carhart’s adopted home—Finding Fontainebleau is a fun, intriguing meditation on time, place, and nationality. I don’t think I can pay it a greater compliment than to report that reading it sent me to Paris’s Gare de Lyon, there to board a train to Fontainebleau, which I saw with new eyes.”—Penelope Rowlands, author of Paris Was Ours

“Charming and vivid and sweet, Finding Fontainebleau is full of the hopeful ambiance of Americans discovering France in the post-war era.”—Alice Kaplan, author of French Lessons and Dreaming in French

“Anyone who grew up in an American baby boom split level will love reading about how the undaunted Carhart family moved from utterly predictable suburban Virginia to the utterly unpredictable environs of Fontainebleau. I learned, I laughed, I marveled, I yearned to transport myself to Fontainebleau.”—David Laskin, author of The Family: A Journey into the Heart of the 20th Century

“Finding Fontainebleau is a family memoir, a chronicle of a remarkable palace, and a social history of the vanished world of post-war France. Most illuminating of all, perhaps, it is a guide to the customs and preoccupations of the French, past and present, whom Thad Carhart writes about with humor, insight, and obvious affection.”—Ross King, author of Brunelleschi’s Dome

“Beautifully written, Thad Carhart’s new book is a delight, happily meandering down memory lane through storybook ‘Phone-Ten-Blow.’ Simply marvelous!”—David Downie, author of Paris, Paris: Journey into the City of Light

“Just as Julia Child’s writing about cooking and eating brought to life France in the 1940s, Thad Carhart uses France’s architecture to describe his own childhood in the 1950s. The Palace of Fontainebleau provides a flamboyant backdrop to his stories of adjusting to French schools, the French language and, naturally, French food. Anyone who has ever felt like a fish out of water will be diverted and informed by Finding Fontainebleau.”—John Baxter, author of The Most Beautiful Walk in the World

“Thad Carhart’s new memoir has all the charm and the deftness with insider knowledge of his much-loved The Piano Shop On the Left Bank. It’s both hilarious and profound, as he gives us in turn his boy’s eye view of a new country and customs and his adult deep appreciation of France, French history and the particular place, Fontainebleau, of the title. A delight, at all its levels. I’ve read it twice already… it’s a book to come back to again and again.”—Rosalind Brackenbury, author of Becoming George Sand

“A delicious journey into a France we never knew and wish we did. Long before mass tourism and globalization France was simple, soulful, and every inch stimulating. Carhart knew it all and shares this with us with the deftness and insight of a master storyteller.”—Leonard Pitt, author of Walks Through Lost Paris and Paris a Journey Through Time

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In