-

Feb 04, 2009 | ISBN 9780307549679

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

The Talking Horse and the Sad Girl and the Village Under the Sea

The Missing Rose

The Testament

The Writer’s Practice

The Eros of Everyday Life

Half-Jew

Black Milk

Do You Believe?

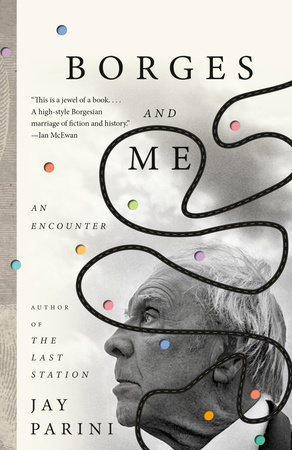

Borges and Me

Praise

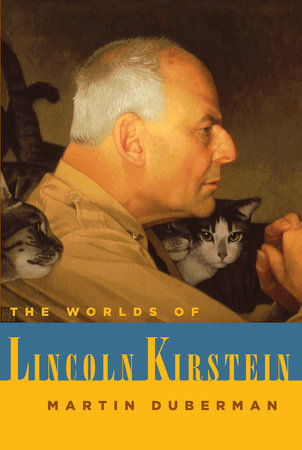

“The arts in America owe plenty to Kirstein–a brilliant, omnivorous personality who died in 1996. From the 1930s to the 80s he worked as a presenter, promoter, fund-raiser and impresario. He made his mark on the dance world by cofounding the New York City Ballet with choreographer George Balanchine. But Kirstein’s worlds were not all highbrow and haughty: Duberman dares to consider Kirstein’s tumultuous, sometimes clandestine and juicy private life as evidence of his high tolerance for risk–a necessary quality when bringing bold new art to a suspicious public.”

–Time Out Chicago

“Impressive . . . gripping . . . Duberman digs deeply, and compassionately, into [Lincoln Kirstein’s] queer core, illuminating how Kirstein’s sexuality shaped his impact on American arts, from the New York City Ballet to Lincoln Center. Dance fans will delight at Duberman’s astute, unsparing critical summation of his bitchy, brilliant subject’s relationship with dance choreographer George Balanchine . . . [Anyone] interested in Manhattan’s gay demimonde will have great fun connecting the homosexual dots.”

–The Bottomline

“The encomia have been arriving this spring, for [Kirstein’s] centenary. He is credited with bringing ballet to America . . . [and] it was [Kirstein and George Balanchine’s] efforts that, in time, created a truly American style of dancing. . . . Duberman enumerates Kirstein’s many endeavors in this important biography, the first. Among other things, Kirstein started the literary journal Hound and Horn and also founded the scholarly journal Dance Index; he helped create a groundbreaking art society at Harvard; he had a role in shaping Lincoln Center; wrote fifteen books and countless articles on dance, literature, art, and film; laid the foundation for a Latin American art collection at the Museum of Modern Art, which was ahead of its time; and endorsed or otherwise was linked with seemingly everyone who mattered in the arts before midcentury . . . Kirstein’s network reminds us how much American arts and letters at midcentury were shaped by a relatively small, largely Harvard-educated, mostly gay group of men who always complained about each other but together accomplished remarkable feats. No one worked more selflessly than Kirstein . . . . Kirstein’s combative letters and diary [entries], quoted at length, enliven Duberman’s biography. . . . In addition to biographies of Paul Robeson, James Russell Lowell, and others, Duberman has written various memoirs and histories of gay culture. He treats Kirstein as a kindred soul, with sympathy . . . [in this] admiring but balanced [biography].”

–Michael Kimmelman, The New York Review of Books

“One hundred years since his birth, historians, critics and aesthetes alike are still trying to figure out just who Lincoln Kirstein really was . . . The title of Kirstein’s first biography, The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein, implies the magnitude of the project. Kirstein, best known for luring Balanchine to America and co-founding with him the School of American Ballet in 1933, and the New York City Ballet in 1946, had his hands in so many pioneering cultural institutions, his social circles strewn across so many continents, that culling together all the necessary sources is in itself a Brobdingnagian task. As part of the 100th anniversary of his birth, City Ballet has dedicated its entire 2007 season to him. The Whitney Museum has mounted a show highlighting works from Kirstein’s personal collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art will do the same this fall. And the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts will open an exhibit of Kirstein’s papers and artworks at the end of this month. Amid the crush of interest, Kirstein’s religion plays no small role. In fact, Duberman’s widely reviewed and well-received biography draws many of its conclusions about Kirstein’s character from his complex religious feeling.”

–Eric Herschthal, The Jewish Week

“Last Friday was the 100th anniversary of Kirstein’s birth, and among many tributes to him now, none can be finer than [the] extraordinarily fine biography of him by Martin Duberman. The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein is wonderfully written, in every way. Like Boswell’s Life of Johnson, this book is great company. . . . Duberman [is] both a first-rate English stylist and a major queer historian . . . [He] has the rare ability to imagine how it was back then without letting go of the perspective we have now.”

–Paul Parish, Bay Area Reporter

“Few people have contributed more to ballet in America than Lincoln Kirstein, who imported George Balanchine and with him founded the New York City Ballet. Kirstein was also instrumental in creating Lincoln Center. One of the most perspicacious analysts of American culture, Duberman has painted a subtle, detailed portrait of a hard-driving force of nature. In addition, his profound knowledge of the byways of gay life in 20th-century America makes him superbly qualified to help us understand what made his subject–butch yet sensitive, bisexual yet lastingly married–tick.”

–The Atlantic Monthly

“A careful, well-assembled portrait of a man who gave his life to the arts he loved. . . . Duberman has done a fine job with a remarkably difficult biographical subject, doing justice to Kirstein’s often-ineffable contributions to projects, and offering a glimpse into the complex consciousness of a talented, irascible, generous and occasionally maddening individual. While not without his faults, Kirstein was a giant of American arts, a colossus who single-handedly paved the way for the flourishing, well-established arts community of today.”

–Saul Austerlitz, San Francisco Chronicle

“[Kirstein] will always be remembered for bringing George Balanchine to America and nurturing the glorious exploit that was the New York City Ballet. But he was also a creative spirit in his own right, the author of audaciously imaginative books about sculpture and dance, as well as of several enduring experiments in the art of autobiography. . . . [His] life was almost incredible in its richness. Kirstein grew up in a wealthy Jewish family in Boston and went to Harvard, where in his early twenties he founded and co-edited a now legendary avant-garde magazine called Hound and Horn and organized the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, which is widely viewed as the precursor to the Museum of Modern Art. His energy and drive, which sometimes seemed almost superhuman, were eventually complicated by periods of acute mental distress, some of which climaxed in hospitalizations. And his personal life has other intricacies, combining as it did a deep and enduring marriage to Fidelma Cadmus, the sister of the painter Paul Cadmus, with many love affairs with young men. . . . Duberman is a very able author. He has produced a book that is fluid, lucid, intelligent. He evaluates the tangled strands of Kirstein’s private life with sensitivity and generosity. . . . What comes through in [his] biography is a tale of two generations–how the old-style philanthropic populism of the early twentieth century was transformed into the avant-garde populism that would give its greatest expression in George Balanchine’s company, the New York City Ballet. . . . Kirstein’s career is a rare, perhaps unique case of old-fashioned public-spiritedness carried to the level of artistic genius. His accomplishments boggle the mind. . . . Nobody has done more to give the loftiest artistic achievements their rightful place in a democratic society. . . . Duberman gives an excellent sense of Kirstein’s almost instinctive genius in organizational matters. . . . In his fierce individualism and his passionate sense of community, in his desire to both safeguard the mysteries of art and make art available to a widening public–in all of this Lincoln Kirstein was quintessentially the American artistic spirit.”

–Jed Perl, The New Republic

“Barely a quarter of the way through The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein, Martin Duberman’s new biography of the arts patron who, through his partnership with choreographer George Balanchine, transformed American ballet, the subject has undertaken–with varying degrees of success–more projects, met more fascinating people and had more lovers than most of his contemporaries, or most anyone else for that matter, would in a lifetime. . . . Kirstein, it seems, wanted to do everything: write novels, plays and poetry; paint; hobnob with the greatest artists and writers of his time; perform the role of a manic impresario with one finger, or arm, in every branch of the arts. As Duberman aptly puts it, he was ‘temperamentally incapable of focusing exclusively on a single project.’. . . . He was restless, full of curiosity and energy and ambition, but unsure of how to apply them or of whether he had the talent to make anything truly great of himself. . . . His personal tragedy was that he was not El Greco, or W. H. Auden, or Balanchine. Indeed, the contrast with Balanchine–whose shadow lurks around the edges of every page–is particularly stark. As Kirstein opines, schemes, suffers doubts and makes plans, one feels the presence of a silent Balanchine working away, making masterpiece after masterpiece, harboring neither the time nor the inclination for self-doubt or distractions. . . . Intermixed with the discussion of the efforts needed to sustain the dance company, Duberman provides an account of his subject’s many other activities . . . [and] also gives an infinitely layered and detailed account of Kirstein’s personal life. . . . There are also long and engaging digressions devoted to Kirstein’s travels . . . Perhaps the most engrossing is Duberman’s account of Kirstein’s World War II experiences. . . . Most remarkably, he was involved in the discovery of an enormous cache of art looted from Europe’s museums in a salt mine in the Rhineland. . . . The impression one is left is of a manic life, with many loose ends and a few casualties, but this can be said: By the time he died, in 1996, his life’s work had been accomplished. . . . This is Kirstein’s centenary year, an appropriate time to consider this accomplishment, and a perfect moment for the publication of Duberman’s tome, the first book devoted entirely to his life and works. Duberman shows himself to be up to the task.”

–Marina Harss, The Forward

“Lincoln Kirstein–patron of the performing, visual, and literary arts; novelist; poet; critic and historian of dance, photography and painting–was one of nature’s titans. . . . But what made him exceptional was that he acted as if his main motto were not ‘I am’ or ‘I do’ but ‘I serve.’ . . . This inspiring self-denying quality is at the heart of Martin Duberman’s new biography, The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein. . . . The book is at its best when Kirstein is successfully engaged on multiple fronts. Mr. Duberman quietly marvels, as any reader must too, at how it was not enough for Kirstein in 1948 to forge the New York City Ballet, his life’s single greatest project. Despite immense struggles of organization and fund-raising that that task required, it also turns out that in 1948 Kirstein was busy in the art world: He organized an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. . . . He also gave a lecture tour ranging from Boston to Chicago and presented the Hunter College premiere of an opera he commissioned. Kirstein had many other years as busy as that, and on just as many different fronts. Mr. Duberman’s biography, drawing on vast resources of unpublished diaries and correspondence, steers us through. . . . [and] once Kirstein’s plural worlds are all well defined, Mr. Duberman is driving in top gear. The narrative for 1945, for example, is particularly exciting, as Kirstein, serving with the American Army in Europe, is central to the recovery of the van Eyck ‘Adoration of the Lamb,’ which the Germans had stolen in 1942 and hidden in a salt mine in Austria. Since the world of performing arts is littered with old sexual gossip, we need biographies as sensitive as this to connect private life to public art with honesty, seriousness and a sense of proportion. It has never been a secret that Kirstein, an intensely sexual creature, was involved with a number of men. . . . Just how he combined this with some serious heterosexual relationships in his youth, and with his marriage to Fidelma Cadmus, is where Mr. Duberman is at his most delicate. . . . And his Kirstein becomes especially vivid when in the company of women. . . . The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein is so richly detailed that it must be consulted by those interested in all whom Kirstein’s life brushed. . . . Much new material emerges here about George Balanchine above all. . . . [Mr. Duberman] shows us, powerfully, the titan’s work, his strength and his incidental afflictions. The book has a gathering force.”

–Alastair Macaulay, The New York Times

“How fitting that one Renaissance man should write the long-overdue biography of another. A playwright, novelist, biographer, and chronicler of queer history and culture, Duberman took on this Herculean task and succeeds brilliantly in bringing a legend to life. He does not neglect Lincoln Kirstein’s accomplishments in literature, art, criticism, dance historiography, and philanthropy, but he necessarily concentrates on Kirstein’s crowning achievement of helping to bring George Balanchine to America and establishing the School of American Ballet and the New York City Ballet. Duberman also shows the private man–the outsize personality plagued by self-doubt; the turbulent relationships with family, friends, and associates; and the lifetime of sexual ambiguity. In the end, you may feel you know Lincoln Kirstein almost as well as you know yourself; Duberman’s research is prodigious, yet he doesn’t let it get in the way of a good story. This extraordinary book is an essential purchase for academic libraries with dance collections and also highly recommended for larger public libraries.”

–M.C. Duhig, Library Journal

“Lincoln Kirstein was, for most of the 20th century, America’s mightiest cultural swizzle stick. He was a skilled critic, historian, art collector and diarist, and a not-bad poet and novelist. But his real gift was for flushing out and nourishing the talent he spotted all around him. . . . Kirstein is best remembered as a ballet visionary . . . In 1933, when he was just a few years out of college, Kirstein brought George Balanchine to America . . . [and] pulled dance to the vital center of American arts. . . . [T]hanks to the crazy brio of its subject, the first half of The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein roars past at terrific speed. . . . In many respects, Duberman is ideally suited to telling this particular story. An adept biographer, he possesses a maverick streak; Duberman publicly announced his homosexuality in 1972 in his book Black Mountain. . . . Kirstein’s own complicated sexuality provides the emotional core of this new book, which is about how a quintessential outsider–‘a queer, Jewish intellectual,’ in Duberman’s words–became the century’s consummate cultural insider. . . . [Duberman] links Kirstein’s sexual obsessions, with grace and insight, to his other achievements. . . . [Kirstein] had enormous charm . . . . [but] among his close friends he exhibited a campy and terrifically bitchy side, and thank God for it, and also for the diary he kept. . . . Kirstein’s [voice] is in living color. . . . [The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein] becomes genuinely moving in its final chapters as Kirstein, who suffered for decades from bipolar disorder, has mental breakdowns and undergoes electric shock. Most affecting is his desire to remain relevant, in the mix. . . . Kirstein’s personality ran to extremes; raging blowups were followed by acts of extreme kindness. . . . ‘You are a pearl of an angel, and yet Mephistopheles as well,’ a friend wrote. The phrase ‘Mephistophelian angel,’ as Duberman notes, is not a bad description of the man . . . [The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein] faithfully captures the busy doings of a 20th century cultural angel.”

–Dwight Garner, The New York Times Book Review

“[The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein] is not only a portrait of a person, but also the map of a sociological matrix–with some of the culture fomented by Kirstein himself. This was a life lived large. . . . [Kirstein] brought Balanchine to New York in 1933, after concluding that Balanchine was the choreographer to establish an American ballet. Before starting several companies that preceded City Ballet, Kirstein founded and funded the School of American Ballet, which would become the training ground for a new breed of dancer–the Balanchine ballerina. . . . [Kirstein also] worked as a government operative in South America under Rockefeller while collecting paintings for the Museum of Modern Art; he brought kabuki theater from Japan to America; he championed the American Shakespeare Festival at Stratford, Conn.; he managed to turn a stint in the Army into a giant art project. Just as large were his appetites, both physical and intellectual. . . . In the opening chapters [of The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein, Duberman] deftly establishes the combination of nature and nurture that informed Kirstein’s character. There was a lot of sex in Lincoln Kirstein’s worlds, some with women but mostly with men. Throughout the narrative, there are lucid explanations of tricky entanglements, as well as an ongoing catalog of the more casual occupations of a man who was, as Mr. Duberman puts it, ‘no slouch at sexual slumming.’ Mr. Duberman is no slouch at telling about it. He also asks questions, often the same ones we find ourselves asking as we read. And he delicately suggests answers. . . . Kirstein pursued his mostly homosexual sex life alongside his marriage to Paul Cadmus’ sister Fidelma. Their long union was marked by attentiveness, love and mental breakdowns on both sides. . . . [Kirstein’s] is the kind of accomplishment that argues for madness as the grim handmaiden of greatness. . . . It’s Martin Duberman’s great accomplishment that he’s given us a unified, empathetic notion of Lincoln Kirstein, entire.”

–Nancy Dalva, New York Observer

“Lincoln Kirstein was one of the 20th century’s great impresarios of art and culture. He started the important literary magazine Hound and Horn, helped in the establishment of the Museum of Modern Art and devoted much of his life and family fortune to sustaining both the School of American Ballet and the much-loved New York City Ballet. Over the years, he also wrote standard histories of dance, essays and monographs on choreographers and artists, a volume of poetry, and even a play that starred the young John Lithgow and Tommy Lee Jones. Kirstein promoted several once-little-known South American artists, and eagerly introduced classical Japanese theater to New York. He was also instrumental in launching the Stratford (Conn.) Shakespeare Festival. Few have contributed more, or more directly, to the artistic enrichment of the nation. The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein, written with authority and elegance by Martin Duberman, is thus an eye-opening account of what one might call the shadow-side of cultural history. For artists, no matter how bohemian their lifestyles, need commissions, theaters, galleries, patrons, critics, students and, sometimes, comforters. All these Lincoln Kirstein worked hard to provide. His friends, and usually his debtors, cut across all the arts. . . . Certainly every headlining name in American dance appears in these pages–from Martha Graham and Agnes de Mille to Jerome Robbins, Paul Taylor, Rudolph Nureyev and Mikhail Baryshnikov. [We] already know a good deal about most of these eminences, though literary and artsy gossip is always welcome. . . . Where Duberman truly excels is in giving equal attention to the people behind the scenes. . . . Martin Duberman has written a superb biography of a man who early on recognized that literature and the fine arts don’t only need creative spirits, they also need champions. Lincoln Kirstein spent his time, his energy and, not least, his money well. We are his beneficiaries.”

–Michael Dirda, Washington Post Book World

“‘He had more arms than Shiva,’ an acquaintance said of the late Lincoln Kirstein, the arts impresario whose 100th birthday is being widely celebrated this year. Among many other things, Kirstein organized the first exhibitions of murals and plainspoken photography for the newly formed Museum of Modern Art, founded an influential literary magazine and, most important, brought George Balanchine to the United States. Together in 1934, the two men opened the School of American Ballet . . . Fifteen years later, they established the New York City Ballet. Without Balanchine, ballet may never have taken hold in this country. It’s not easy to draw a portrait of someone who never sat still. It’s especially hard when that person’s genius consisted of laying the groundwork for other geniuses. Acclaimed historian and biographer Martin Duberman succeeds in The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein, the first biography of the impresario, because he paints Kirstein’s life as the restless man lived it–great aesthetic ambitions alternating with cruises to waterfront dives. Duberman has written memoirs of his own gay youth and middle age, award-winning plays and biographies, and dozens of essays on civil rights. As a pan-intellectual himself, he knows not to make too neat a sense of Kirstein’s life. [He] looks outward through Kirstein’s sardonic eyes at the whole world parading by–high society and bohemian fringe, from the 1920s onward. . . . Kirstein thought ballet could ‘restore to the world the human scale again’–if only Balanchine would cooperate. . . . Balanchine treated Kirstein as an office boy with a wad of cash, and kept him out of the loop. Eventually, Kirstein came to understand that Balanchine didn’t need American themes to make a ‘sharp, abrupt, jazzy’ American ballet, and that it hardly mattered anyway how American his art was. . . . On his end, Balanchine finally committed himself to the idea of a New York company. The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein is a gripping account of the birth of an institution: the steps and missteps; the perpetual hunt for money; the fact that it wasn’t clear whether the goal could be achieved or what precisely the goal was. Duberman also offers an absorbing portrait of an era. . . . As a scholar of gay history, Duberman is particularly good at setting the Kirstein story within the shifting terms of what it meant to be gay. . . . The biography is emotionally satisfying. . . . We come to love [Kirstein]–and ache for him. The institutions to which he was most devoted–the New York City Ballet and its school–achieved great success over time, but his own life was increasingly overtaken by mania and depression. This fierce, good giant ended his life by closing the shades. When a friend brought by some art books that had once interested him, Kirstein said, ‘I don’t care anymore,’ and went back to sleep.” –Apollinaire Scherr, Newsday, cover

“Engrossing . . . Unfailingly generous . . . The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein is a necessarily intrepid work. It is the first book entirely devoted to [Kirstein’s] prodigious life and career and Duberman’s mission has been made especially daunting by the quantity of material that Kirstein left behind, as well as by Kirstein’s tendency, in his autobiographical work, to obfuscate, exaggerate, and lie . . . The happy news is that Duberman has proved equal to the difficulties both of the job and of the highly outspoken, often irascible man. He dispels the fog of myth that has spread around Kirstein’s early years; he gleans hard facts from tricks and poses; he stands up to Kirstein’s prejudices and carefully explicates his most gleefully outrageous opinions in a way that informs us broadly about the subject as well as about the workings of Kirstein’s mind. . . . Lincoln Kirstein [dedicated himself early on] to the construction of a full-scale unreal world–magic, music, color genius . . . . He had so many choices, talents and interests . . . [He] had a good hand for drawing and a strong desire to paint. But he was also ‘deeply addicted’ to ballet, and he had literary ambitions that were nearly as pressing: while a freshman at Harvard he started a magazine, Hound & Horn, that drew support from Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, and he went on to write criticism, poetry, at least one ‘moral tragedy,’ and a novel. In his junior year, he helped start the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, which was a forerunner of the Museum of Modern Art, where he signed on as an advisor in 1930, when he was not quite twenty-three. Three years later, he brought the young Russian choreographer George Balanchine to America, and together they founded both the School of American Ballet and its attendant company, New York City Ballet. . . . Kirstein carefully transcribed Balanchine’s promise, ‘he could do wonders.’ And, thanks to Kirstein, he did. . . . In the nineteen-fifties, he [also] played an important role in the American Shakespeare Festival. . . . The shear breadth of Kirstein’s endeavor has made him appear to many people to be the last historical example of the Renaissance man. . . . When times were good, a splendid social life was overseen by his wife, Fidelma, and the guests–from the dancers of the corps de ballet to W. H. Auden–were the very best in body and mind. . . . About Kirstein’s enduring personal appeal, despite the inroads of [mental] illness, Duberman leaves us in no doubt. . . . Like all good biographers, Duberman is part detective and part judge, but the most appealing aspect of his book is that he seems to love his subject more than Kirstein ever loved himself.”

–Claudia Roth Pierpont, The New Yorker

“[As] cofounder of the School of American Ballet in 1934 and as the éminence grise who battled so valiantly for three decades to create New York City Ballet [Lincoln Kirstein] became one of the most dedicated and impassioned patrons of the arts in 20th Century America. . . . [He] was a precocious intellectual who founded a distinguished literary magazine called Hound and Horn while still an undergraduate at Harvard University. . . . [and was deeply] involved with the Museum of Modern Art from its creation in 1929. . . . [But above] all, [he] created a haven for brilliant Russian émigré George Balanchine. . . . Kirstein’s great gift to the American people [has been] the forms of classical ballet displayed through native themes. . . . Martin Duberman, the author of the highly compelling new biography The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein, has ideal credentials for such a complex project. Distinguished professor emeritus of history at the City University of New York. . . . he has interviewed countless people who knew Kirstein, which enables him to separate scandalous rumors from realities, and also to judge the veracity of Kirstein’s diary entries. . . . [He] has [also] written three biographies, including one of Paul Robeson, and several volumes about his own life as a gay man. . . . His insightful preparation for this work informs it throughout. . . . [a] narrative [that] concerns art, first and foremost, with Kirstein’s sexual affairs [with both men and women] interwoven. . . . [The] result is an empathetic portrait that nevertheless includes warts and all. Kirstein was not an easy man, given to tactless and hysterical outbursts, especially as he aged, and the profile we receive is exceedingly judicious. . . . [The book will appeal to] anyone engaged by the sheer complexities of a highly creative human personality driven by a worthy and challenging goal. . . . [Kirstein’s] explosive persona, always larger than life, is richly illuminated by Duberman’s splendid achievement.”

–Michael Kammen, Chicago Tribune

“George Balanchine may have given ballet in America its signature look and rhythm, but it was Lincoln Kirstein who provided the push that made it all possible. This month and next, New York pays homage to the grandfather of American ballet with a biography, exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, among other institutions, and, perhaps most fitting co-founder of the New York City Ballet, an entire NYCB season, ‘Kirstein 100: A Tribute,’ dedicated to the man who brought Balanchine to America in 1934.”

–Joel Lobenthal, The New York Sun

“Duberman is uniquely qualified to chronicle the many faceted life of influential arts advocate Lincoln Kirstein. . . . [He] details Kirstein’s herculean efforts to establish choreographer George Balanchine in the U.S. and tells phenomenal stories. . . . A crucial force in the vitality of the Museum of Modern Art and Lincoln Center, Kirstein led a complicated personal life. . . . Duberman offers a remarkably candid and profoundly insightful portrait of a man of dazzling gifts and convictions.”

–Donna Seaman, Booklist

“A central figure in 20th-century American modernism, Lincoln Kirstein edited a pioneering literary magazine and was the driving force behind George Balanchine’s revolutionary New York City Ballet. Bancroft Prize—winner Duberman reveals in his absorbing biography a man blessed, agonizingly, with great artistic taste and vision unaccompanied by artistic talent . . . [Kirstein’s] was a high-wire life sustained by a stupendous manic energy (later darkening into demented fits that necessitated electroshock) and enlivened by a parade of lovers of both sexes . . . Kirstein met everyone from Martha Graham to General Patton. Through Kirstein’s funny, perceptive diary jottings and letters, Duberman paints an engaging portrait of bohemian New York and its high-society patrons . . . Duberman conjures an indelible sense of a creative urge that became a torturous pilgrimage toward an enigmatic muse.”

–Publishers Weekly

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In