This article was written by Swapna Krishna and originally appeared on Unbound Worlds.

Oral histories have become increasingly popular ways to tell the story of important moments in pop culture. They take away the barrier between writer and storyteller; it makes you feel closer to the narrative because all you’re seeing are people’s own words, arranged in a way that tells a coherent story.

However, despite the fact that an oral history may seem like an easy endeavor, it’s anything but. That aforementioned arrangement is key to being able to follow the narrative and understand opposing points of view. Mark A. Altman and Edward Gross have become experts at the enormous work that goes into these books; they edited a two-part oral history of “Star Trek,” The Fifty-Year Mission, an oral history of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and “Angel” with Slayers and Vampires, and now they’ve moved onto the sci-fi classic “Battlestar Galactica” with So Say We All, out August 21st from Tor Books. Unbound Worlds spoke with Mark Altman on how exactly they put these enormous books together and where they might head from here.

Unbound Worlds: What first made you interested in conducting and compiling oral histories?

Mark A. Altman: It all began with the 50th anniversary of “Star Trek.” We felt we in a unique position to tell the history of “Star Trek” in a way that no one else could. Even then, it took some convincing from Ed to bring me around. It wasn’t till after reading the wonderful oral histories of “Saturday Night Live” and MTV that I realized this was a great format to chronicle the history of Trek that had never been done and also be true to the Rashomon-like history of the franchise. To Ed’s credit, I’m delighted I did do the book with him and I keep trying to get out, but he keeps pulling me back in.

UW: What’s the research and interview process like? What about the process of putting it all together into one coherent story?

MAA: Years of intensive research and hundreds of hours of interviews are where we start. But you’re absolutely right, perhaps the biggest challenge is taking literally hundreds of thousands of pages of transcripts and turning them into a coherent narrative. We always say it’s like attending the greatest dinner party in the world with 200–300 people and then getting them to tell these amazing stories they’ve never shared before and prodding them to tell you more, even the things they don’t want to or might have forgotten about.

UW: Is it ever hard to decide what makes it in versus what to cut?

MAA: Yes, because these books could be thousands of pages instead of hundreds if we used all the great stories we had. Thankfully, Macmillan indulged us on the Trek book and let us bifurcate it into two volumes to do justice to the entire 50 years, and I couldn’t be more pleased with the reception we received. Otherwise, that would have been hard to distill down and we would have lost some amazing stories and anecdotes. Buffy and Galactica have been easier to keep at less than 1000 pages, but it’s still a challenge given the bountiful material we’ve had access to in terms of the candor and passion of the people we’ve spoken to.

UW: You work with a co-author, Edward Gross. How is the work divided between the two of you? How do you collaborate?

MAA: It depends on the subject. In the case of the first Trek volume, we really built on each others’ work and interviews. For the second volume, we divided up the series but then flipped everything. There was no way I was doing “Voyager,” I was very insistent on that fact. For Buffy & Angel, Ed primarily took “Angel” and I did “Buffy” but there was definitely a cross-over in interviews and we revise each others sections.

BSG was definitely the most clearly defined. I did 1978 and 1980 primarily and he did Ron Moore’s series, which isn’t to say we didn’t both contribute to each section, but he did the heavy lifting on his section and vice versa. And when I was finished I was really unhappy with the 1980 section. I didn’t feel I had really added anything new to the story and I knew no one was ever likely to write about the subject of this dreadful series again, so I started from scratch intending to really do a deep dive, did a ton more interviews, and it’s one of my favorite chapters in any of the books now.

UW: You’ve done oral histories for “Star Trek,” “Buffy”/”Angel,” and now “Battlestar Galactica.” Was there one that was your favorite? Not because of the property, but because of process or uncovered secrets?

MAA: I agreed to do all these books, first and foremost because I’m a fan of all these shows. These books are primarily a hobby for me, my day job is as a writer/producer for film and television series which is quite time consuming so if I’m going to give up my hiatus, weekends, and nights for a book, it has to be something I’m passionate about. “Star Trek” was no-brainer, but “Buffy” was super fun because it not only gave me a chance to write about a show I loved as well as my family, but also talk to several people I worked with in my other capacity like Felicia Day and Sean Astin, who were guest stars on an episode of “The Librarians” I wrote and, of course, Christian Kane.

But then “Galactica” was also a big deal for me because I grew up on the 1978 series and always felt it was the Rodney Dangerfield of sci-fi series. Despite its many flaws, it was a really significant and impressive series that had a lot to do with influencing the future of television, even if people don’t recognize that. And, of course, Ron Moore’s series is just a major milestone in genre storytelling and one of the greatest TV series ever produced so to have the kind of access we had thanks to Ron and tell the real story behind this show was really remarkable and we were honored to do so.

UW: “Battlestar Galactica” had a long-lasting impact on science fiction as a genre. What does it mean to you personally, and how do you interpret its legacy?

MAA: It was the sci-fi “Sopranos.” Ron and David Eick created a series that will stand the test of time and really was part of the dawn of peak and binge-able television. It’s very significant and a really remarkable accomplishment. The original series deserves more respect but is often derided because it was perceived as a “Star Wars” rip-off. But it actually, if sometimes clumsily, dealt with some very heady themes and had some of the most remarkable production design and visual effects in any genre film or TV series ever.

It was also a show about a literal family unlike “Trek,” which was a figurative one, which made it unique as well and there are some remarkable episodes and an ingenious premise that made “BSG“ 2004 possible. It was one of the few sci-fi series to deal with theology and spirituality as well. What we also chronicle is the unique place Universal Television was at the end of the ‘70s in the waning days of the studio system when talent was under contract and half the show creators were either drunk or on drugs, and work was done by a small coterie of largely white men who all knew each other and would all get hired on each others shows. I found that period absolutely fascinating and it’s amazing to see how dramatically TV has changed.

UW: You’ve traced quite a bit of Ron D. Moore’s career through “The Next Generation,” “Deep Space Nine,” “Voyager,” and now “Battlestar Galactica.” What was it like to work with him, and what do you think these books say about his career?

MAA: Ron is a remarkable talent. That’s no secret. But what people might not know is what a great guy he is. A total mensch. I first met Ron back in the heyday of “TNG” when I used to interview him for the late, great Cinefantastique magazine. He has remained steadfast and loyal even when I was less than effusive with my praise for his films like “Generations” (which I savaged) and yet he remained very supportive of my own career. I think he’s incredibly savvy and smart and has a passion that is unparalleled among genre creators. He has been incredibly supportive of Ed and I. With the “Trek” books, he spent literally tens of hours on the phone with Ed speaking to him with complete candor and thoughtfulness.

When it came time to do So Say We All, he literally reached out to the entire cast and crew on our behalf and told them to speak to us honestly about the show and it really opened the floodgates so that we were able to talk to everyone involved in the new series from Eddie on down to the grips — okay maybe not the grips, but mostly everyone.

UW: This is the last book in your oral history trilogy. Why is that, and if you could open the door to exploring more shows and properties, what might they be?

MAA: Well, that’s not quite true. When I wrote [the introduction to So Say We All], I thought it would be. That I said everything I had to say. And while it’s likely to be our last oral history of a genre TV show—although never say never again—we’re already committed to another oral history of a major film series for Tor that we’re writing now and have a few other projects that we’re discussing so like I say; I keep trying to get out, but they keep pulling me back in.

A big part of this is how much I enjoy my working relationship with Ed Gross as well as my fantastic editorial team at Tor, but also how much I love these TV series and films we’re writing about. There’s a great line in the mediocre Michael Crichton film “Looker,” when Albert Finney is asked to do plastic surgery on a really beautiful girl and he wants to turn down the assignment and he’s advised by a colleague, “You better do it or someone less competent will.” That’s kind of how I feel about these oral histories too.

This article was written by Swapna Krishna and originally appeared on Unbound Worlds.

Oral histories have become increasingly popular ways to tell the story of important moments in pop culture. They take away the barrier between writer and storyteller; it makes you feel closer to the narrative because all you’re seeing are people’s own words, arranged in a way that tells a coherent story.

However, despite the fact that an oral history may seem like an easy endeavor, it’s anything but. That aforementioned arrangement is key to being able to follow the narrative and understand opposing points of view. Mark A. Altman and Edward Gross have become experts at the enormous work that goes into these books; they edited a two-part oral history of “Star Trek,” The Fifty-Year Mission, an oral history of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and “Angel” with Slayers and Vampires, and now they’ve moved onto the sci-fi classic “Battlestar Galactica” with So Say We All, out August 21st from Tor Books. Unbound Worlds spoke with Mark Altman on how exactly they put these enormous books together and where they might head from here.

Unbound Worlds: What first made you interested in conducting and compiling oral histories?

Mark A. Altman: It all began with the 50th anniversary of “Star Trek.” We felt we in a unique position to tell the history of “Star Trek” in a way that no one else could. Even then, it took some convincing from Ed to bring me around. It wasn’t till after reading the wonderful oral histories of “Saturday Night Live” and MTV that I realized this was a great format to chronicle the history of Trek that had never been done and also be true to the Rashomon-like history of the franchise. To Ed’s credit, I’m delighted I did do the book with him and I keep trying to get out, but he keeps pulling me back in.

UW: What’s the research and interview process like? What about the process of putting it all together into one coherent story?

MAA: Years of intensive research and hundreds of hours of interviews are where we start. But you’re absolutely right, perhaps the biggest challenge is taking literally hundreds of thousands of pages of transcripts and turning them into a coherent narrative. We always say it’s like attending the greatest dinner party in the world with 200–300 people and then getting them to tell these amazing stories they’ve never shared before and prodding them to tell you more, even the things they don’t want to or might have forgotten about.

UW: Is it ever hard to decide what makes it in versus what to cut?

MAA: Yes, because these books could be thousands of pages instead of hundreds if we used all the great stories we had. Thankfully, Macmillan indulged us on the Trek book and let us bifurcate it into two volumes to do justice to the entire 50 years, and I couldn’t be more pleased with the reception we received. Otherwise, that would have been hard to distill down and we would have lost some amazing stories and anecdotes. Buffy and Galactica have been easier to keep at less than 1000 pages, but it’s still a challenge given the bountiful material we’ve had access to in terms of the candor and passion of the people we’ve spoken to.

UW: You work with a co-author, Edward Gross. How is the work divided between the two of you? How do you collaborate?

MAA: It depends on the subject. In the case of the first Trek volume, we really built on each others’ work and interviews. For the second volume, we divided up the series but then flipped everything. There was no way I was doing “Voyager,” I was very insistent on that fact. For Buffy & Angel, Ed primarily took “Angel” and I did “Buffy” but there was definitely a cross-over in interviews and we revise each others sections.

BSG was definitely the most clearly defined. I did 1978 and 1980 primarily and he did Ron Moore’s series, which isn’t to say we didn’t both contribute to each section, but he did the heavy lifting on his section and vice versa. And when I was finished I was really unhappy with the 1980 section. I didn’t feel I had really added anything new to the story and I knew no one was ever likely to write about the subject of this dreadful series again, so I started from scratch intending to really do a deep dive, did a ton more interviews, and it’s one of my favorite chapters in any of the books now.

UW: You’ve done oral histories for “Star Trek,” “Buffy”/”Angel,” and now “Battlestar Galactica.” Was there one that was your favorite? Not because of the property, but because of process or uncovered secrets?

MAA: I agreed to do all these books, first and foremost because I’m a fan of all these shows. These books are primarily a hobby for me, my day job is as a writer/producer for film and television series which is quite time consuming so if I’m going to give up my hiatus, weekends, and nights for a book, it has to be something I’m passionate about. “Star Trek” was no-brainer, but “Buffy” was super fun because it not only gave me a chance to write about a show I loved as well as my family, but also talk to several people I worked with in my other capacity like Felicia Day and Sean Astin, who were guest stars on an episode of “The Librarians” I wrote and, of course, Christian Kane.

But then “Galactica” was also a big deal for me because I grew up on the 1978 series and always felt it was the Rodney Dangerfield of sci-fi series. Despite its many flaws, it was a really significant and impressive series that had a lot to do with influencing the future of television, even if people don’t recognize that. And, of course, Ron Moore’s series is just a major milestone in genre storytelling and one of the greatest TV series ever produced so to have the kind of access we had thanks to Ron and tell the real story behind this show was really remarkable and we were honored to do so.

UW: “Battlestar Galactica” had a long-lasting impact on science fiction as a genre. What does it mean to you personally, and how do you interpret its legacy?

MAA: It was the sci-fi “Sopranos.” Ron and David Eick created a series that will stand the test of time and really was part of the dawn of peak and binge-able television. It’s very significant and a really remarkable accomplishment. The original series deserves more respect but is often derided because it was perceived as a “Star Wars” rip-off. But it actually, if sometimes clumsily, dealt with some very heady themes and had some of the most remarkable production design and visual effects in any genre film or TV series ever.

It was also a show about a literal family unlike “Trek,” which was a figurative one, which made it unique as well and there are some remarkable episodes and an ingenious premise that made “BSG“ 2004 possible. It was one of the few sci-fi series to deal with theology and spirituality as well. What we also chronicle is the unique place Universal Television was at the end of the ‘70s in the waning days of the studio system when talent was under contract and half the show creators were either drunk or on drugs, and work was done by a small coterie of largely white men who all knew each other and would all get hired on each others shows. I found that period absolutely fascinating and it’s amazing to see how dramatically TV has changed.

UW: You’ve traced quite a bit of Ron D. Moore’s career through “The Next Generation,” “Deep Space Nine,” “Voyager,” and now “Battlestar Galactica.” What was it like to work with him, and what do you think these books say about his career?

MAA: Ron is a remarkable talent. That’s no secret. But what people might not know is what a great guy he is. A total mensch. I first met Ron back in the heyday of “TNG” when I used to interview him for the late, great Cinefantastique magazine. He has remained steadfast and loyal even when I was less than effusive with my praise for his films like “Generations” (which I savaged) and yet he remained very supportive of my own career. I think he’s incredibly savvy and smart and has a passion that is unparalleled among genre creators. He has been incredibly supportive of Ed and I. With the “Trek” books, he spent literally tens of hours on the phone with Ed speaking to him with complete candor and thoughtfulness.

When it came time to do So Say We All, he literally reached out to the entire cast and crew on our behalf and told them to speak to us honestly about the show and it really opened the floodgates so that we were able to talk to everyone involved in the new series from Eddie on down to the grips — okay maybe not the grips, but mostly everyone.

UW: This is the last book in your oral history trilogy. Why is that, and if you could open the door to exploring more shows and properties, what might they be?

MAA: Well, that’s not quite true. When I wrote [the introduction to So Say We All], I thought it would be. That I said everything I had to say. And while it’s likely to be our last oral history of a genre TV show—although never say never again—we’re already committed to another oral history of a major film series for Tor that we’re writing now and have a few other projects that we’re discussing so like I say; I keep trying to get out, but they keep pulling me back in.

A big part of this is how much I enjoy my working relationship with Ed Gross as well as my fantastic editorial team at Tor, but also how much I love these TV series and films we’re writing about. There’s a great line in the mediocre Michael Crichton film “Looker,” when Albert Finney is asked to do plastic surgery on a really beautiful girl and he wants to turn down the assignment and he’s advised by a colleague, “You better do it or someone less competent will.” That’s kind of how I feel about these oral histories too.

Photo by Felix Mittermeier on Unsplash

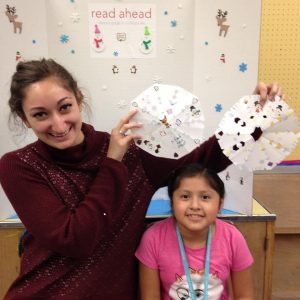

MM: We understand each other more as we continue to get to know each other. We aren’t just reading together the whole time. When we first started she would come in and we would sit down and read together, but as we’ve gotten to know each other we’ve become a lot more comfortable, spending more time talking and learning about each other.

MM: We understand each other more as we continue to get to know each other. We aren’t just reading together the whole time. When we first started she would come in and we would sit down and read together, but as we’ve gotten to know each other we’ve become a lot more comfortable, spending more time talking and learning about each other.

RA: Is there a book you’ve read together that has been particularly successful?

MM: She has such a range of interests – we’re always reading about something new. One book that she really loved was “The Day The Crayons Quit” by Drew Daywalt – it really is a great story and she was so excited by it.

RA: Is there a book you’ve read together that has been particularly successful?

MM: She has such a range of interests – we’re always reading about something new. One book that she really loved was “The Day The Crayons Quit” by Drew Daywalt – it really is a great story and she was so excited by it.

My next trip is in August. All of the kids have gone on trips with me before and for two of them this will be their fourth time. I always tell the kids that my job is to keep them safe and theirs is to make sure we have fun. They are good at that. I try.

My next trip is in August. All of the kids have gone on trips with me before and for two of them this will be their fourth time. I always tell the kids that my job is to keep them safe and theirs is to make sure we have fun. They are good at that. I try.