Johnny Cash’s son reflects on his father, his legacy, and his poetry.

FOREWORD: REDEMPTIONS

My father had many faces. There was much that made up the man. If you think you “know” John R Cash, think again. There are many layers, so much beneath the surface.

First, I knew him to be fun. Within the first six years of my life, if asked what Dad was to me I would have emphatically responded: “Dad is fun!” This was my simple foundation for my enduring relationship with my father.

This is the man he was. He never lost this.

To those who knew him well—family, friends, coworkers alike—the one essential thing that was blazingly evident was the light and laughter within my father’s heart. Typically, though his common image may be otherwise, he was not heavy and dark, but loving and full of color.

Yet there was so much more . . .

For one thing—he was brilliant. He was a scholar, learned in ancient texts, including those of Flavius Josephus and unquestionably of the Bible. He was an ordained minister and could easily hold his own with any theologian or historian. His books on ancient history, such as Gibbon’s

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, were annotated, read, reread and worn, his very soul deeply ingrained into their threadbare pages. I still have some of these books. When I hold them, when I touch the pages, I can sense my father in some ways even more profoundly than in his music.

My father was an entertainer. This is, of course, one of the most marked and enduring manifestations. There are thousands upon thousands of new Johnny Cash fans every year, inspired by the music, talent, and—I believe hugely—by the mystery of the man.

My dad was a poet. He saw the world through unique glasses, with simplicity, spirituality, and humor. He loved a good story and was quick to find comedy, even in bleak circumstances. This is evident in one of the last songs he wrote within his lifetime, “Like the 309”:

It should be a while before I see Dr. Death

So it would sure be nice if I could get my breath

Well, I’m not the crying nor the whining kind

Till I hear the whistle of the 309

Of the 309, of the 309

Put me in my box on the 309.

Take me to the depot, put me to bed

Blow an electric fan on my gnarly old head

Everybody take a look, see I’m doing fine

Then load my box on the 309

On the 309, on the 309

Put me in my box on the 309.

Dad was asthmatic and had great difficulty breathing during the last months of his life. On top of all this, he suffered with recurring bouts of pneumonia. Still, through the gift of laughter, he found the strength to face these infirmities. This recording is steeped in irony, although made mere days before his passing. His voice is weak, yet the mirth in his soul rings true.

Dad was many things, yes. He was tortured throughout his life by sadness and addiction. His tragic youth was marked by the loss of his best friend and brother Jack, who died as the result of a horrible accident when John R was only twelve. Jack was a deeply spiritual young man, kind and protective of his two-year-younger brother. Perhaps it was this sadness and mourning that partly defined my father’s poetry and songs throughout his life. He was likewise defined at the end of his life by the loss of my mother, June Carter. When she passed, their love was more beautiful than ever before: unconditional and kind.

Still, it could not be said that any of this—darkness, love, sadness, music, joy, addiction—wholly defined the man. He was all of these things and none of them. Complicated, but what could be said that speaks the essential truth? What prevails? The music, of course . . . but likewise . . .

the words.

All that made up my father is to be found in this book, within these “forever words.”

When my parents died, they left behind a monstrous amassment of “stuff.” They just didn’t throw anything away. Each and every thing was a treasure, but none more than my father’s handwritten letters, poems, and documents, ranging through the entirety of his life. There was a huge amount of paper—his studies of the book of Job, his handwritten autobiography

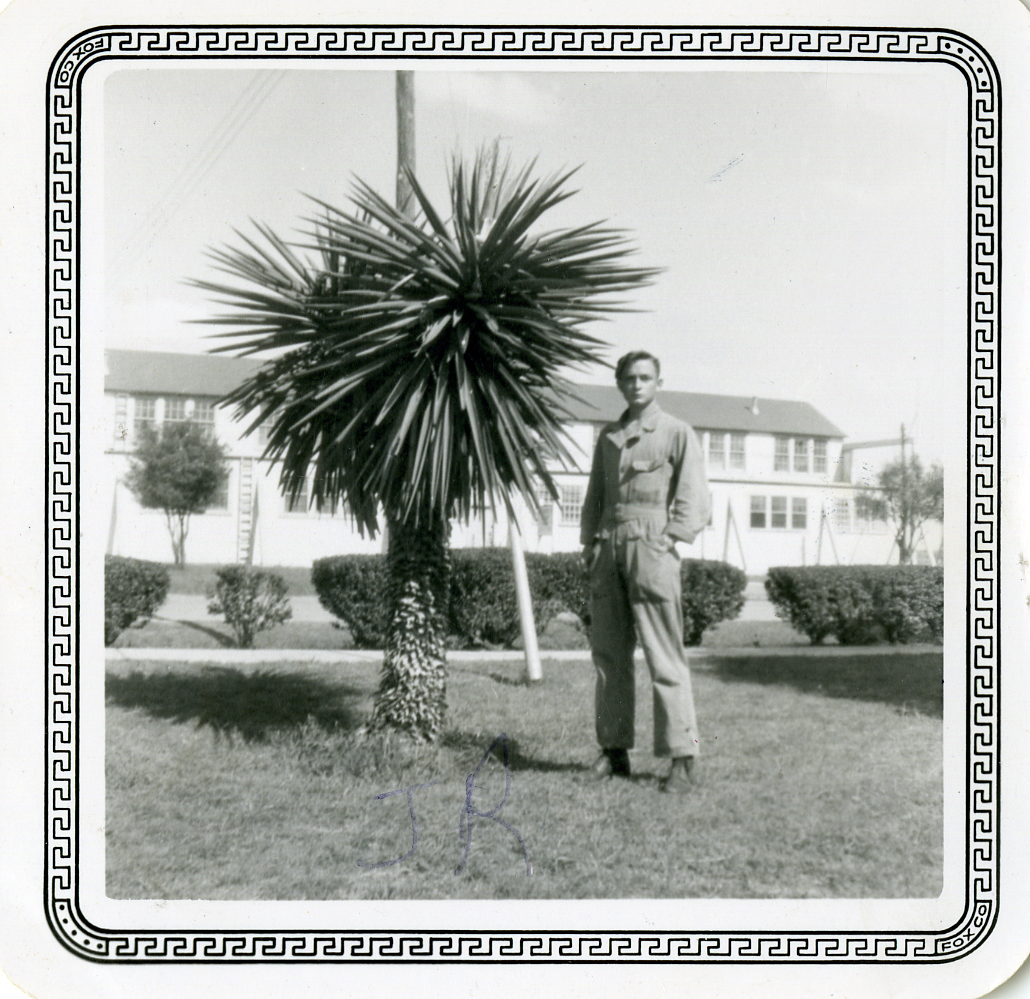

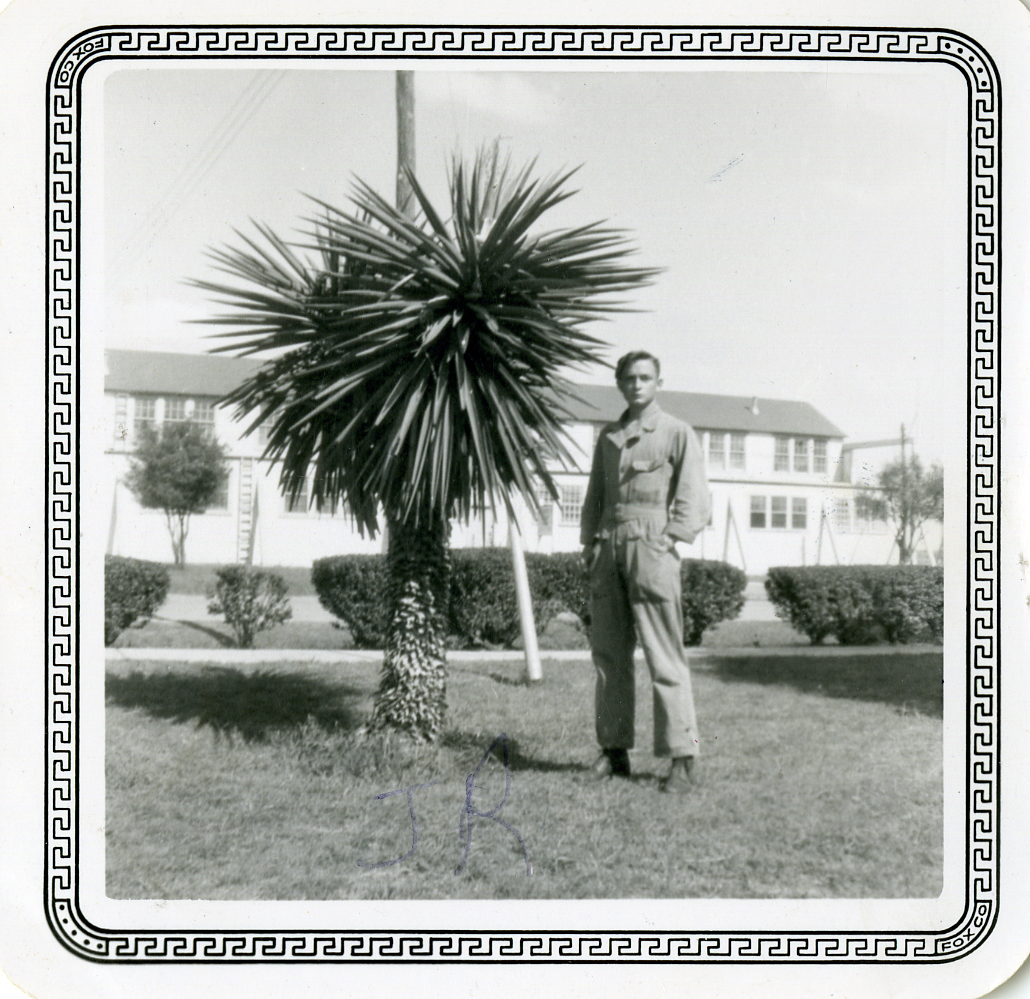

Man in Black, his letters to my mother, and likewise to his first wife, Vivian, from the 1950s. Dad was a writer, and he never ceased. His writings ranged through every stage of his life: from the poems of a naive yet undeniably brilliant sixteen-year-old to later comprehensive studies on the life of the Apostle Paul. The more I have looked, the more I have understood of the man.

When I hold these papers, I feel his presence within the handwriting; it brings him back to me. I remember how he held his pen, how his hand shook a bit, but how careful and proud he was of his penmanship—and how determined and courageous he was. Some of these pages are stained with coffee, perhaps the ink smudged. When I read these pages, I feel the love he carried in those hands. I once again feel the closeness of my father, how he cared so deeply for the creative endeavor; how he cared for his loved ones.

There are some of these I feel he would have wanted to be shared, some whose genius and brilliance simply demanded to be heard. I hope and believe the ones chosen within these pages are those he would want read by the world.

Finally, it is not only the strength of his poetic voice that speaks to me, it is his very life enduring and coming anew with these writings. It is in these words my father sings a new song, in ways he has never done before. Now, all these years past, the

words tell a full tale; with their release, he is with us again, speaking to our hearts, making us laugh, and making us cry.

The music will endure, this is true. The music will endure, this is true. But also, the

words. It is ultimately evident within these words that the sins and sadnesses have failed, that goodness commands and triumphs. To me, this book is a redemption, a cherished healing.

Forever.

John Carter Cash

35,000 feet above western Arkansas, flying east . . .

First, I knew him to be fun. Within the first six years of my life, if asked what Dad was to me I would have emphatically responded: “Dad is fun!” This was my simple foundation for my enduring relationship with my father.

This is the man he was. He never lost this.

To those who knew him well—family, friends, coworkers alike—the one essential thing that was blazingly evident was the light and laughter within my father’s heart. Typically, though his common image may be otherwise, he was not heavy and dark, but loving and full of color.

Yet there was so much more . . .

For one thing—he was brilliant. He was a scholar, learned in ancient texts, including those of Flavius Josephus and unquestionably of the Bible. He was an ordained minister and could easily hold his own with any theologian or historian. His books on ancient history, such as Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, were annotated, read, reread and worn, his very soul deeply ingrained into their threadbare pages. I still have some of these books. When I hold them, when I touch the pages, I can sense my father in some ways even more profoundly than in his music.

First, I knew him to be fun. Within the first six years of my life, if asked what Dad was to me I would have emphatically responded: “Dad is fun!” This was my simple foundation for my enduring relationship with my father.

This is the man he was. He never lost this.

To those who knew him well—family, friends, coworkers alike—the one essential thing that was blazingly evident was the light and laughter within my father’s heart. Typically, though his common image may be otherwise, he was not heavy and dark, but loving and full of color.

Yet there was so much more . . .

For one thing—he was brilliant. He was a scholar, learned in ancient texts, including those of Flavius Josephus and unquestionably of the Bible. He was an ordained minister and could easily hold his own with any theologian or historian. His books on ancient history, such as Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, were annotated, read, reread and worn, his very soul deeply ingrained into their threadbare pages. I still have some of these books. When I hold them, when I touch the pages, I can sense my father in some ways even more profoundly than in his music.

My father was an entertainer. This is, of course, one of the most marked and enduring manifestations. There are thousands upon thousands of new Johnny Cash fans every year, inspired by the music, talent, and—I believe hugely—by the mystery of the man.

My dad was a poet. He saw the world through unique glasses, with simplicity, spirituality, and humor. He loved a good story and was quick to find comedy, even in bleak circumstances. This is evident in one of the last songs he wrote within his lifetime, “Like the 309”:

My father was an entertainer. This is, of course, one of the most marked and enduring manifestations. There are thousands upon thousands of new Johnny Cash fans every year, inspired by the music, talent, and—I believe hugely—by the mystery of the man.

My dad was a poet. He saw the world through unique glasses, with simplicity, spirituality, and humor. He loved a good story and was quick to find comedy, even in bleak circumstances. This is evident in one of the last songs he wrote within his lifetime, “Like the 309”:

Dad was many things, yes. He was tortured throughout his life by sadness and addiction. His tragic youth was marked by the loss of his best friend and brother Jack, who died as the result of a horrible accident when John R was only twelve. Jack was a deeply spiritual young man, kind and protective of his two-year-younger brother. Perhaps it was this sadness and mourning that partly defined my father’s poetry and songs throughout his life. He was likewise defined at the end of his life by the loss of my mother, June Carter. When she passed, their love was more beautiful than ever before: unconditional and kind.

Still, it could not be said that any of this—darkness, love, sadness, music, joy, addiction—wholly defined the man. He was all of these things and none of them. Complicated, but what could be said that speaks the essential truth? What prevails? The music, of course . . . but likewise . . . the words.

All that made up my father is to be found in this book, within these “forever words.”

When my parents died, they left behind a monstrous amassment of “stuff.” They just didn’t throw anything away. Each and every thing was a treasure, but none more than my father’s handwritten letters, poems, and documents, ranging through the entirety of his life. There was a huge amount of paper—his studies of the book of Job, his handwritten autobiography Man in Black, his letters to my mother, and likewise to his first wife, Vivian, from the 1950s. Dad was a writer, and he never ceased. His writings ranged through every stage of his life: from the poems of a naive yet undeniably brilliant sixteen-year-old to later comprehensive studies on the life of the Apostle Paul. The more I have looked, the more I have understood of the man.

Dad was many things, yes. He was tortured throughout his life by sadness and addiction. His tragic youth was marked by the loss of his best friend and brother Jack, who died as the result of a horrible accident when John R was only twelve. Jack was a deeply spiritual young man, kind and protective of his two-year-younger brother. Perhaps it was this sadness and mourning that partly defined my father’s poetry and songs throughout his life. He was likewise defined at the end of his life by the loss of my mother, June Carter. When she passed, their love was more beautiful than ever before: unconditional and kind.

Still, it could not be said that any of this—darkness, love, sadness, music, joy, addiction—wholly defined the man. He was all of these things and none of them. Complicated, but what could be said that speaks the essential truth? What prevails? The music, of course . . . but likewise . . . the words.

All that made up my father is to be found in this book, within these “forever words.”

When my parents died, they left behind a monstrous amassment of “stuff.” They just didn’t throw anything away. Each and every thing was a treasure, but none more than my father’s handwritten letters, poems, and documents, ranging through the entirety of his life. There was a huge amount of paper—his studies of the book of Job, his handwritten autobiography Man in Black, his letters to my mother, and likewise to his first wife, Vivian, from the 1950s. Dad was a writer, and he never ceased. His writings ranged through every stage of his life: from the poems of a naive yet undeniably brilliant sixteen-year-old to later comprehensive studies on the life of the Apostle Paul. The more I have looked, the more I have understood of the man.

When I hold these papers, I feel his presence within the handwriting; it brings him back to me. I remember how he held his pen, how his hand shook a bit, but how careful and proud he was of his penmanship—and how determined and courageous he was. Some of these pages are stained with coffee, perhaps the ink smudged. When I read these pages, I feel the love he carried in those hands. I once again feel the closeness of my father, how he cared so deeply for the creative endeavor; how he cared for his loved ones.

When I hold these papers, I feel his presence within the handwriting; it brings him back to me. I remember how he held his pen, how his hand shook a bit, but how careful and proud he was of his penmanship—and how determined and courageous he was. Some of these pages are stained with coffee, perhaps the ink smudged. When I read these pages, I feel the love he carried in those hands. I once again feel the closeness of my father, how he cared so deeply for the creative endeavor; how he cared for his loved ones.

There are some of these I feel he would have wanted to be shared, some whose genius and brilliance simply demanded to be heard. I hope and believe the ones chosen within these pages are those he would want read by the world.

Finally, it is not only the strength of his poetic voice that speaks to me, it is his very life enduring and coming anew with these writings. It is in these words my father sings a new song, in ways he has never done before. Now, all these years past, the words tell a full tale; with their release, he is with us again, speaking to our hearts, making us laugh, and making us cry.

There are some of these I feel he would have wanted to be shared, some whose genius and brilliance simply demanded to be heard. I hope and believe the ones chosen within these pages are those he would want read by the world.

Finally, it is not only the strength of his poetic voice that speaks to me, it is his very life enduring and coming anew with these writings. It is in these words my father sings a new song, in ways he has never done before. Now, all these years past, the words tell a full tale; with their release, he is with us again, speaking to our hearts, making us laugh, and making us cry.

The music will endure, this is true. The music will endure, this is true. But also, the words. It is ultimately evident within these words that the sins and sadnesses have failed, that goodness commands and triumphs. To me, this book is a redemption, a cherished healing. Forever.

John Carter Cash

35,000 feet above western Arkansas, flying east . . .

The music will endure, this is true. The music will endure, this is true. But also, the words. It is ultimately evident within these words that the sins and sadnesses have failed, that goodness commands and triumphs. To me, this book is a redemption, a cherished healing. Forever.

John Carter Cash

35,000 feet above western Arkansas, flying east . . .