Tag Archives: writing

Read John Carter Cash’s foreword to his father’s Forever Words

First, I knew him to be fun. Within the first six years of my life, if asked what Dad was to me I would have emphatically responded: “Dad is fun!” This was my simple foundation for my enduring relationship with my father.

This is the man he was. He never lost this.

To those who knew him well—family, friends, coworkers alike—the one essential thing that was blazingly evident was the light and laughter within my father’s heart. Typically, though his common image may be otherwise, he was not heavy and dark, but loving and full of color.

Yet there was so much more . . .

For one thing—he was brilliant. He was a scholar, learned in ancient texts, including those of Flavius Josephus and unquestionably of the Bible. He was an ordained minister and could easily hold his own with any theologian or historian. His books on ancient history, such as Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, were annotated, read, reread and worn, his very soul deeply ingrained into their threadbare pages. I still have some of these books. When I hold them, when I touch the pages, I can sense my father in some ways even more profoundly than in his music.

First, I knew him to be fun. Within the first six years of my life, if asked what Dad was to me I would have emphatically responded: “Dad is fun!” This was my simple foundation for my enduring relationship with my father.

This is the man he was. He never lost this.

To those who knew him well—family, friends, coworkers alike—the one essential thing that was blazingly evident was the light and laughter within my father’s heart. Typically, though his common image may be otherwise, he was not heavy and dark, but loving and full of color.

Yet there was so much more . . .

For one thing—he was brilliant. He was a scholar, learned in ancient texts, including those of Flavius Josephus and unquestionably of the Bible. He was an ordained minister and could easily hold his own with any theologian or historian. His books on ancient history, such as Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, were annotated, read, reread and worn, his very soul deeply ingrained into their threadbare pages. I still have some of these books. When I hold them, when I touch the pages, I can sense my father in some ways even more profoundly than in his music.

My father was an entertainer. This is, of course, one of the most marked and enduring manifestations. There are thousands upon thousands of new Johnny Cash fans every year, inspired by the music, talent, and—I believe hugely—by the mystery of the man.

My dad was a poet. He saw the world through unique glasses, with simplicity, spirituality, and humor. He loved a good story and was quick to find comedy, even in bleak circumstances. This is evident in one of the last songs he wrote within his lifetime, “Like the 309”:

My father was an entertainer. This is, of course, one of the most marked and enduring manifestations. There are thousands upon thousands of new Johnny Cash fans every year, inspired by the music, talent, and—I believe hugely—by the mystery of the man.

My dad was a poet. He saw the world through unique glasses, with simplicity, spirituality, and humor. He loved a good story and was quick to find comedy, even in bleak circumstances. This is evident in one of the last songs he wrote within his lifetime, “Like the 309”:

It should be a while before I see Dr. Death So it would sure be nice if I could get my breath Well, I’m not the crying nor the whining kind Till I hear the whistle of the 309 Of the 309, of the 309 Put me in my box on the 309. Take me to the depot, put me to bed Blow an electric fan on my gnarly old head Everybody take a look, see I’m doing fine Then load my box on the 309 On the 309, on the 309 Put me in my box on the 309.

Dad was asthmatic and had great difficulty breathing during the last months of his life. On top of all this, he suffered with recurring bouts of pneumonia. Still, through the gift of laughter, he found the strength to face these infirmities. This recording is steeped in irony, although made mere days before his passing. His voice is weak, yet the mirth in his soul rings true. Dad was many things, yes. He was tortured throughout his life by sadness and addiction. His tragic youth was marked by the loss of his best friend and brother Jack, who died as the result of a horrible accident when John R was only twelve. Jack was a deeply spiritual young man, kind and protective of his two-year-younger brother. Perhaps it was this sadness and mourning that partly defined my father’s poetry and songs throughout his life. He was likewise defined at the end of his life by the loss of my mother, June Carter. When she passed, their love was more beautiful than ever before: unconditional and kind.

Still, it could not be said that any of this—darkness, love, sadness, music, joy, addiction—wholly defined the man. He was all of these things and none of them. Complicated, but what could be said that speaks the essential truth? What prevails? The music, of course . . . but likewise . . . the words.

All that made up my father is to be found in this book, within these “forever words.”

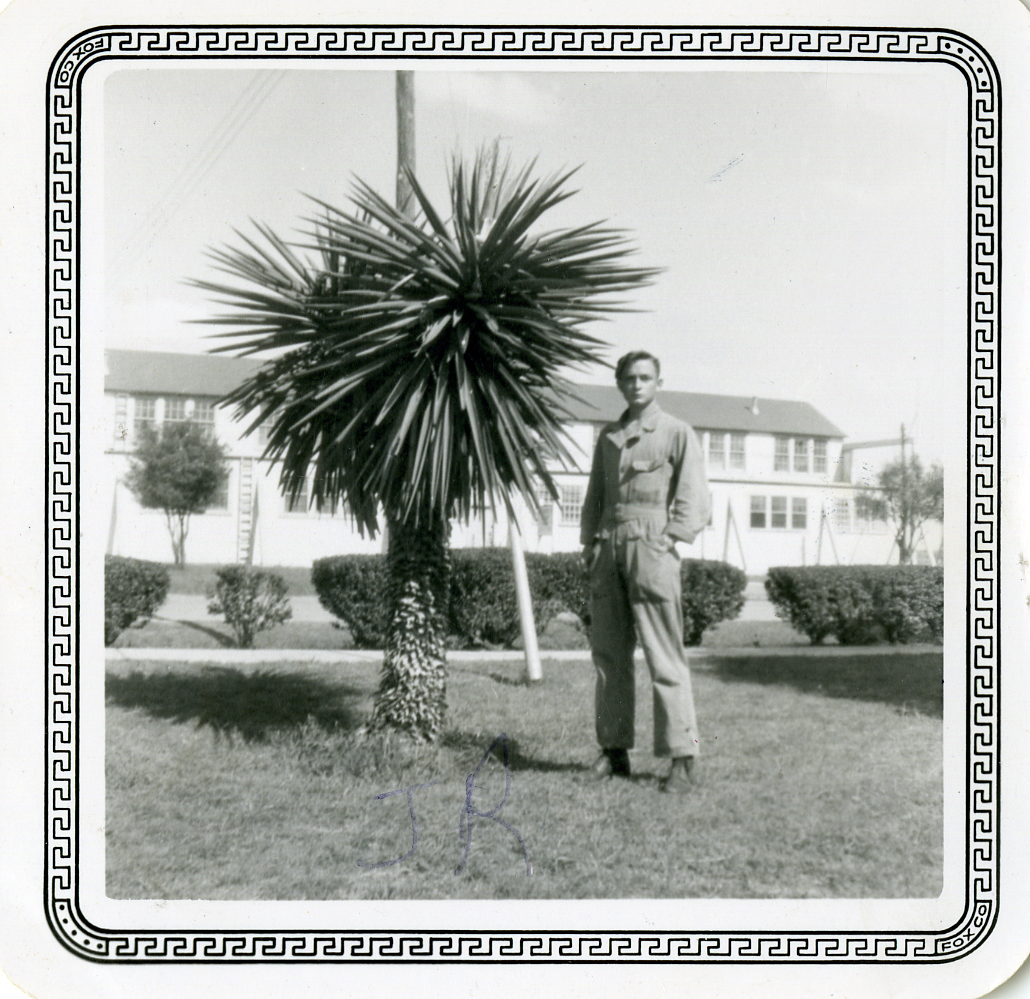

When my parents died, they left behind a monstrous amassment of “stuff.” They just didn’t throw anything away. Each and every thing was a treasure, but none more than my father’s handwritten letters, poems, and documents, ranging through the entirety of his life. There was a huge amount of paper—his studies of the book of Job, his handwritten autobiography Man in Black, his letters to my mother, and likewise to his first wife, Vivian, from the 1950s. Dad was a writer, and he never ceased. His writings ranged through every stage of his life: from the poems of a naive yet undeniably brilliant sixteen-year-old to later comprehensive studies on the life of the Apostle Paul. The more I have looked, the more I have understood of the man.

Dad was many things, yes. He was tortured throughout his life by sadness and addiction. His tragic youth was marked by the loss of his best friend and brother Jack, who died as the result of a horrible accident when John R was only twelve. Jack was a deeply spiritual young man, kind and protective of his two-year-younger brother. Perhaps it was this sadness and mourning that partly defined my father’s poetry and songs throughout his life. He was likewise defined at the end of his life by the loss of my mother, June Carter. When she passed, their love was more beautiful than ever before: unconditional and kind.

Still, it could not be said that any of this—darkness, love, sadness, music, joy, addiction—wholly defined the man. He was all of these things and none of them. Complicated, but what could be said that speaks the essential truth? What prevails? The music, of course . . . but likewise . . . the words.

All that made up my father is to be found in this book, within these “forever words.”

When my parents died, they left behind a monstrous amassment of “stuff.” They just didn’t throw anything away. Each and every thing was a treasure, but none more than my father’s handwritten letters, poems, and documents, ranging through the entirety of his life. There was a huge amount of paper—his studies of the book of Job, his handwritten autobiography Man in Black, his letters to my mother, and likewise to his first wife, Vivian, from the 1950s. Dad was a writer, and he never ceased. His writings ranged through every stage of his life: from the poems of a naive yet undeniably brilliant sixteen-year-old to later comprehensive studies on the life of the Apostle Paul. The more I have looked, the more I have understood of the man.

When I hold these papers, I feel his presence within the handwriting; it brings him back to me. I remember how he held his pen, how his hand shook a bit, but how careful and proud he was of his penmanship—and how determined and courageous he was. Some of these pages are stained with coffee, perhaps the ink smudged. When I read these pages, I feel the love he carried in those hands. I once again feel the closeness of my father, how he cared so deeply for the creative endeavor; how he cared for his loved ones.

When I hold these papers, I feel his presence within the handwriting; it brings him back to me. I remember how he held his pen, how his hand shook a bit, but how careful and proud he was of his penmanship—and how determined and courageous he was. Some of these pages are stained with coffee, perhaps the ink smudged. When I read these pages, I feel the love he carried in those hands. I once again feel the closeness of my father, how he cared so deeply for the creative endeavor; how he cared for his loved ones.

There are some of these I feel he would have wanted to be shared, some whose genius and brilliance simply demanded to be heard. I hope and believe the ones chosen within these pages are those he would want read by the world.

Finally, it is not only the strength of his poetic voice that speaks to me, it is his very life enduring and coming anew with these writings. It is in these words my father sings a new song, in ways he has never done before. Now, all these years past, the words tell a full tale; with their release, he is with us again, speaking to our hearts, making us laugh, and making us cry.

There are some of these I feel he would have wanted to be shared, some whose genius and brilliance simply demanded to be heard. I hope and believe the ones chosen within these pages are those he would want read by the world.

Finally, it is not only the strength of his poetic voice that speaks to me, it is his very life enduring and coming anew with these writings. It is in these words my father sings a new song, in ways he has never done before. Now, all these years past, the words tell a full tale; with their release, he is with us again, speaking to our hearts, making us laugh, and making us cry.

The music will endure, this is true. The music will endure, this is true. But also, the words. It is ultimately evident within these words that the sins and sadnesses have failed, that goodness commands and triumphs. To me, this book is a redemption, a cherished healing. Forever.

John Carter Cash

35,000 feet above western Arkansas, flying east . . .

The music will endure, this is true. The music will endure, this is true. But also, the words. It is ultimately evident within these words that the sins and sadnesses have failed, that goodness commands and triumphs. To me, this book is a redemption, a cherished healing. Forever.

John Carter Cash

35,000 feet above western Arkansas, flying east . . .

Listen: Tara Clancy on Brooklyn, Shakespeare and The Moth

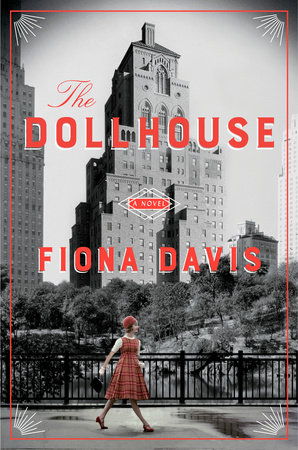

Writing Tips from Fiona Davis, author of The Dollhouse

Writing Tips from Jillian Cantor, author of The Hours Count

We know readers tend to be writers too, so we feature writing tips from our authors. Who better to offer advice, insight, and inspiration than the authors you admire? They’ll answer several questions about their work, share their go-to techniques and more. Now, get writing!

How would you recommend creating and getting to know your characters? The absolute first thing I do is decide my main characters’ names. I feel like I need to know someone’s name before I can start to know him or her. My favorite place to figure out first names is the Social Security popular baby names website, where you can view name popularity by birth year (back to 1879) to see what common and (uncommon) names were in the year your character was born. After I decide names, I’ll start to make notes of other things, like birthdays/age or relationships to other characters, quirks, where a character lives, or things he/she likes or dislikes. But I start drafting pretty soon into this process. I mostly learn and get to really know my characters as I’m writing the first draft, thinking about what they do and how they react and speak when I put them in different situations. So I think the best way I get to know my characters is to write them. By the time I get to the end of the first draft, they’re often different than what I started with (and I know them much better). But then I go back and revise. After developing an idea, what is the first action you take when beginning to write? The first line of novel is really important. It sets the tone for the entire book. I want it to show what the book is ultimately about, but also to be interesting and hook the reader. When I first start thinking about and developing an idea I always start thinking about first lines. I jot down ideas, often for weeks or months. But, I don’t wait for the perfect first line before I start drafting a book. I begin with the first one that comes to me and then I keep writing from there to get my first draft going. So just the act of getting words and ideas down on the page is the most important action I take in order to actually start writing. I set a goal for myself – usually 3-5 pages a day – and I make myself sit down and write something, make some progress in the draft, even if it’s ultimately terrible and will all be changed in revision. Most of the time the first line that appears in the final draft of the book is not at all what I started with. I keep thinking on that first line, even as I keep writing the first draft. Usually I don’t understand enough about the story myself until I finish or get most of the way through a first draft. So I start writing at the beginning, but 9 times out of 10 that beginning changes by the time I make it to the end! Is there something you do to get into a writing mood? Somewhere you go or something you do to get thinking? I always write at home, and I need quiet to write. I negotiate my writing schedule around my kids’ schedules so I usually write while my kids are at school during weekdays, or very early in the mornings on the weekends or during the summer when my kids are home – really, whenever I can find uninterrupted quiet each day. I have an office in my house where I can shut the door, and I do write there, but when no one else is home I also write at my kitchen table. I like to drink coffee while I write, and that always helps to get me thinking. Or when I get stuck, I’ll exercise. Taking a long walk, run, or hike, often helps me work through a plot a point I was stuck on or figure out a problem in my story. What’s the best piece of advice you have received? The best advice, and I got this from a writing professor in grad school, is simply, “butt in chair.” As in, just sit down and force yourself to write something, no matter what it is or how terrible you think it is. The hardest part is making yourself sit down to do it. So I don’t let myself make excuses – I put my butt in the chair every morning and write something. What are three or four books that influenced your writing, or had a profound effect on you? I read Bird By Bird by Anne Lamott in the first fiction writing class I took, and I still have a copy on the shelf in my office. I love what she writes about first drafts and I feel like it’s still important to give myself permission to write something terrible the first time around as long as I write something. I’m a big believer in the importance of revision! Black and Blue by Anna Quindlen is one of my favorite novels, and the first I read by her. I come back to it, and her novels, again and again, because I feel like I learn so much about sympathetic character development from her. The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, which I first read in college, always makes me think about writing characters in a world different from our own today (which is applicable for writing historical fiction as well) and the fact that characters still need to first be inherently human and relatable, no matter how different their world is from the one we know.Learn more about the book below!

Listen: Catherine Banner talks small-town Italy, forgotten folk stories, and inspiration drawn from economic crisis

Listen: Delia Ephron talks writing, eating habits, vacationing, and marriage.

Writing Tips from Alice Mattison, author of The Kite and the String

Lisa Cron, author of Story Genius, on what makes a good story… and what doesn’t!

- A great voice.

- A dramatic plot.

- Gorgeous writing.

But while those things are often in a good story, they are not what make a good story. In fact, they don’t make a story at all. Instead, at best, they simply convey – albeit in luscious language — a bunch of surface things that happen. Such well-written, story-less prose is known in the trade as a beautifully written “who cares?”

But while those things are often in a good story, they are not what make a good story. In fact, they don’t make a story at all. Instead, at best, they simply convey – albeit in luscious language — a bunch of surface things that happen. Such well-written, story-less prose is known in the trade as a beautifully written “who cares?”

So what is a story? In a nutshell: A story is a single, unavoidable problem that grows, escalates and complicates, forcing the protagonist to make an internal change.The secret of story is that it’s about internal change, not an external plot-based one. Everything that happens in a story gets its meaning and emotional weight based on one thing: the internal conflict it spurs within the protagonist as she struggles with what the hell to do next in order to solve the plot problem. This is as true of a quiet literary novel as it is of a heart-pounding thriller. The drama doesn’t come from the events themselves, it comes from how those events intensify the protagonist’s internal struggle. That’s what makes us care. That’s what triggers the intoxicating sense of urgency that catapults readers out of their own lives into the protagonist’s. Here’s the bonus for writers: The deeper you dig into this struggle, the more meaningful – and thus beautiful — your prose becomes. Great writing comes from great stories, not the other way around. Learn more about the book below: