We know readers tend to be writers too, so we feature writing tips from our authors. Who better to offer advice, insight, and inspiration than the authors you admire? They’ll answer several questions about their work, share their go-to techniques and more. Now, get writing!

Did you always want to write? How did you start your career as an author?

I started writing quite young. My mother worked in a deli in Montreal and when I was little, she would take me with her for the day. I would write monster stories and fairy tales for her (and me) on the backs of the paper placemats—mainly to entertain myself but also for the sheer pleasure and escape of building another world. I remember being flush with joy and excitement when I thought I had a novel on my hands at the age of 7 or so. Needless to say, that didn’t pan out.

Is there something you do to get into a writing mood? Somewhere you go or something you do to get thinking?

My main routine is to write in the morning in silence. I make coffee and then I turn everything off, including my phone and Internet connection, for as long as I can either stand or get away with. If I write in the morning like this, then I’m able to return to the story at various times later in the day and work on it regardless of where I am or the level of distraction. But I need those anchoring morning hours of silence and focus with the story in order to do that.

I also love Aimee Bender’s idea of the writing contract so I’ve done that with friends as well. You basically contractually promise to adhere to a certain number of writing rules that you determine (it could be a daily word count, or a number of hours per day) and then you check in daily via email with a ‘mentor’ (a friend) who confirms you’re moving forward. You do it with an overall writing goal in mind—like a novel—to be achieved by the contract’s end. It’s quite loose, but what I love is that you make your own writing goal, your own rules for how you’ll reach it, and then you are required to follow through. I did it with a writer friend last summer, and we both completed drafts of our novels. And I’m doing one now with another writer friend for the revision. I like the collaborative aspect of it too—writing, while exhilarating, can also be quite a lonely, cave-dwelling business. It’s nice to come out of the cave every day and check in with a friend.

After developing an idea, what is the first action you take when beginning to write?

I’m often inspired by a moment of tension that I’ve either observed, experienced or imagined—being in a fitting room with a dress that doesn’t fit, for example. I’ll take that point of tension and I’ll sit with it, trying to describe it with as much intimate, immediate and honest detail as possible. I’ll scrutinize it, draw it out, let myself imagine around it. By exploring a moment of tension like this, I find it acquires more layers and consequence, and a story will often emerge. Once I have the story, I can push that tension further still—in some cases, to its limits.

What are three or four books that influenced your writing, or had a profound affect on you?

My favorite stories have always been the ones that felt very intimate, like the writer really gave something vital in themselves to the telling of the story. For that reason perhaps, I love all of the novels of Jean Rhys—I love how urgent her writing is, how her characters experience outsiderness and alienation in ways that feel so immediate and visceral. Russell Hoban is another favorite. Not only is he a beautiful writer, but I love how he conceives that space between what we perceive to be reality and reality—a space that is inherently fraught with our anxieties, desires and dreams—as truly imaginative. In The Lion of Boaz-Jachin and Jachin-Boaz, a son’s anger at his father is an actual lion stalking the streets of London. Perhaps this is a throw back to my placemat writing days, but I’ve always been deeply inspired and excited by fairy tales and Alice in Wonderland narratives. I adore The Torn Skirt by Rebecca Godfrey, which is essentially a feverdreamy, high stakes Alice in Wonderland for adults. The first person voice is also incredible. And of course, The Winter’s Tale by Shakespeare, which is a strange, rich and wondrous fairy tale. The wonderful thing about reading or seeing Shakespeare is that no matter what hot mess of emotions you’re experiencing in your life—pettiness, hatred, fear, desire, joy, sadness, love, resentment—they become eerily performed by the play in question. Will’s got you covered. Within the stories, the characters, the language, there’s room for it all. Also, I love humor. Without writers like Dorothy Parker, Lydia Davis or Lorrie Moore, I would feel lost.

Learn more about Mona Awad’s new book below!

Austin, in Knopf Production, is reading How to Set a Fire and Why by Jesse Ball.

Find out more about the book here:

Austin, in Knopf Production, is reading How to Set a Fire and Why by Jesse Ball.

Find out more about the book here:

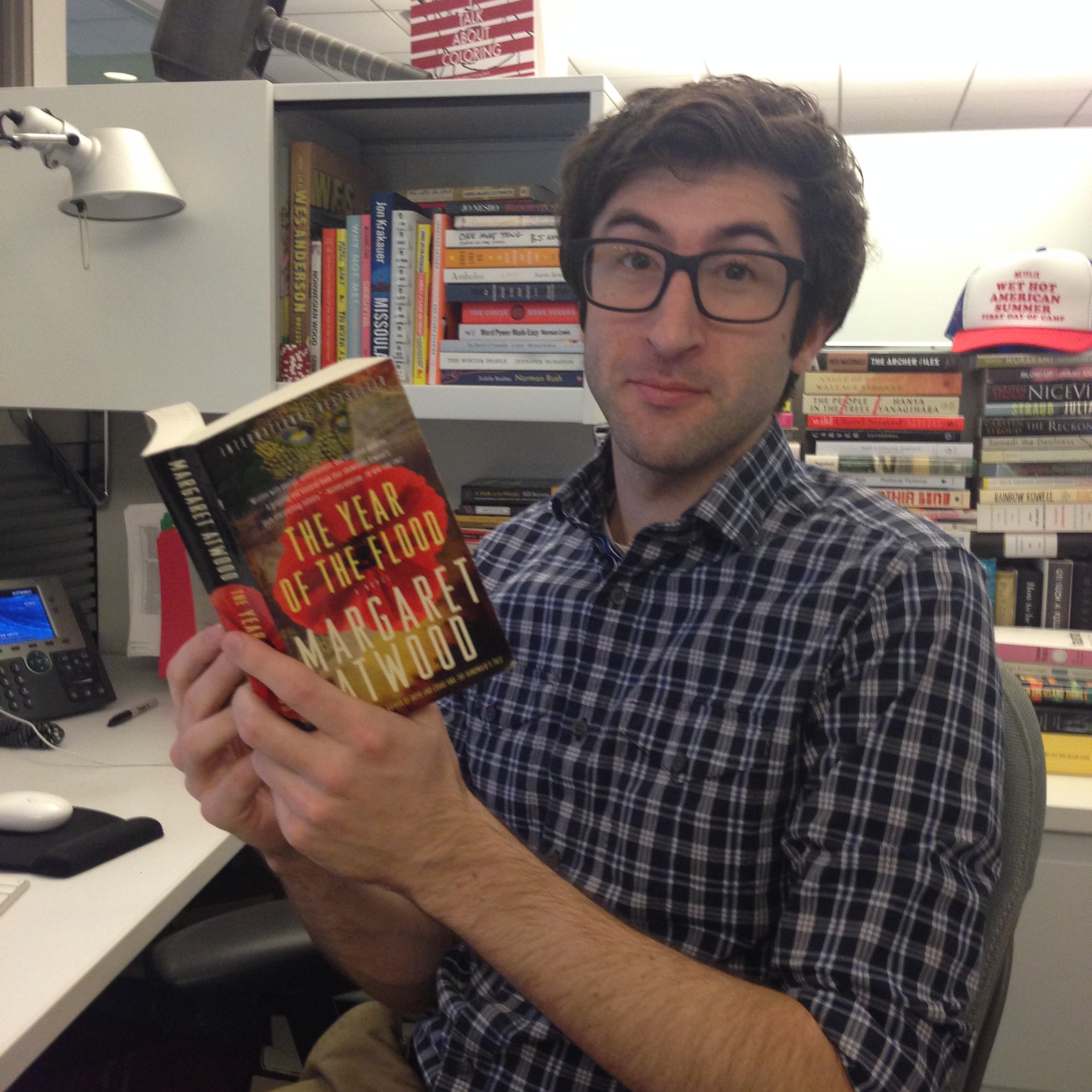

Adam, Social Media and Digital Publishing for Vintage and Anchor books, is reading The Year of the Flood by Margaret Atwood.

Find out more about the book here:

Adam, Social Media and Digital Publishing for Vintage and Anchor books, is reading The Year of the Flood by Margaret Atwood.

Find out more about the book here:

It’s been such a joy to watch the excitement build for this one-of-a-kind novel, with sales falling under its spell, and booksellers singing its praises. Along with being an

It’s been such a joy to watch the excitement build for this one-of-a-kind novel, with sales falling under its spell, and booksellers singing its praises. Along with being an  Kristin, in consumer marketing, is reading an advance reading copy of The Girls by Emma Cline

Find out more about the book here:

Kristin, in consumer marketing, is reading an advance reading copy of The Girls by Emma Cline

Find out more about the book here: