Hillary Manton Lodge is the author of the critically acclaimed Two Blue Doors series and the Plain and Simple duet. Jane of Austin is her sixth novel. In her free time, she enjoys experimenting in the kitchen, graphic design, and finding new walking trails. She resides outside of Memphis, Tennessee with her husband and two pups. She can be found online at www.hillarymantonlodge.com.

My grandmother read everything. Books about travel, antiques, architecture, mushrooms. She read murder mysteries by the stack until my grandfather passed; afterwards, her tastes veered into sweet romances, narrow paperbacks with titles like The Sophisticated Urchin and Destiny is a Flower.

But she loved the classics best, Jane Austen most of all. When I was nine, she gave me a battered paperback Penguin Classics copy of Pride & Prejudice. I didn’t make much progress with at the time – I was an advanced reader, but not that advanced – so my first experiences of Austen were in film. First, with the 1940 Greer Garson and Laurence Olivier version, and later with the 1995 Andrew Davies mini-series for the BBC.

When the latter aired on Masterpiece Theater, I visited my grandparents’ home every Sunday night for six weeks while we watched Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth argue and make eyes at each other. My grandfather made us an English dinner – or rather, his interpretation of one – and asked if they were “dahn-cing yet?” As a twelve-year-old with two younger siblings, the dedicated time with my grandparents felt special and grown-up.

But it wasn’t until I was an adult that I was able to read and appreciate Austen’s work. As a high-schooler, the subtext of Emma flew right over my head. But as an adult – and author – I was able to see the work, craft, and wicked humor just beneath the surface. I made my way with pleasure through Pride & Prejudice, Persuasion, Sense & Sensibility, and Emma – Mansfield Park and Northanger Abbey are next on the list.

I read them in time to talk to my grandmother about the text; she passed away at the age of 100, and by then the one-two punch of dementia and hearing loss had made it difficult to converse on a specific topic for any length of time. But we were able to compare notes, and we shook our heads over what a pill Darcy could be.

A deep dive into Austen for Jane of Austin, then, felt natural. My editor gave me the title and free reign over it, and after a little consideration I reached for Sense & Sensibility – after all, my last four books had featured self-contained women who navigated the world while keeping it arm’s length. Who better to buck that trend than a character modeled after Marianne Dashwood?

But updating a novel set during the early 19th Century has its challenges. For starters, there’s the teeny fact that women can not only inherit both property and money, but can have jobs without being cast out of polite society. When necessary, I borrowed from other Austen novels, and gave my version of Marianne – Jane, in my own novel – depth that would have eluded the original 17-year-old character.

There were challenges, but also pleasures. And it’s the pleasures that are why we revisit Austen’s work so often. Her books are populated with people we know. I’ve met Fanny Dashwoods and Mr. Eltons and Mary Musgroves – we all have. Her stories resonate because they’re inhabited by our own neighbors, parents, and co-workers.

But the familiarity of Austen’s literary world should never be mistaken for simplicity. As I wrote Jane of Austin, I got stuck. A lot. And when I did, I returned to the text. Every time, there was something there. Whether it was a witty line or an insightful scene, I always found something to springboard off of and keep the story rolling.

And that’s the beauty of Austen’s work. There’s always something there. There’s wit and romance on the surface. For the deep thinker, there’s sharp social commentary and character study. And no matter the novel, there’s the pleasure in knowing that there will always, somewhere, be dancing.

Learn about the book here:

As we herald our newest Pulitzer Prize winners – in an unprecedented four of the five Letters categories – we celebrate all of the 131 titles published by a current or legacy imprint of Penguin and Random House that have been awarded a Pulitzer since the inception of the Prize more than a century ago.

They include some of the defining fiction, nonfiction, and poetry of the past 100 years, such as:

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz in 2008:

Ghost Wars by Steve Coll in 2005:

Lindbergh by Scott Berg in 1999;

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck in 1940;

The Road by Cormac McCarthy in 2006;

The Power Broker by Robert A. Caro in 1975;

Promises: Poems 1945-56 by Robert Penn Warren in 1958;

Humboldt’s Gift by Saul Bellow in 1976;

The Magnificent Ambersons by Booth Tarkingtonin 1919; and

Common Ground by J. Anthony Lukas in 1986.

Here are our four newest Pulitzer winners!

Biography

The Return

The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land in Between by Hisham Matar.

Edited by Noah Eaker.

Pulitzer citation: “For a first-person elegy for home and father that examines with controlled emotion the past and present of an embattled region.”

Susan Kamil, Hisham Matar’s publisher at Random House, said, “It’s thrilling to see Hisham’s work so recognized by the Pulitzer jury.

The Return is about Hisham’s personal search for his father, but his art elevates it into a universal quest for justice.”

The Return previously won the inaugural PEN/Jean Stein Book Award.

Fiction

The Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead.

Edited by Bill Thomas.

Pulitzer citation: “For a smart melding of realism and allegory that combines the violence of slavery and the drama of escape in a myth that speaks to contemporary America.”

Colson Whitehead commented, “I don’t even know what to say — this has been a crazy ride ever since I handed the book in to my editor. I’m incredibly grateful to everyone who picked up a copy and dug it, and to all the kind folks who championed it along the way — the booksellers, the reviewers, the awesome Oprah Winfrey, and the judges. It’s a nice day to put ‘New York, New York’ on the headphones and walk around city making crazy gestures at strangers.”

The Underground Railroad has sold over 825,000 copies in the United States across all formats. An Oprah’s Book Club 2016 selection, #1

New York Times bestseller, a

New York Times Book Review Ten Best Books of 2016 selection and the winner of the 2016 National Book Award for Fiction, the book chronicles young Cora’s journey as she makes a desperate bid for freedom in the antebellum South. After escaping her Georgia plantation for the rumored Underground Railroad, Cora discovers no mere metaphor, but an actual railroad full of engineers and conductors, and a secret network of tracks and tunnels beneath the Southern soil.

General Nonfiction

Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City

Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City by Matthew Desmond.

Edited by Amanda Cook.

Pulitzer citation: “For a deeply researched exposé that showed how mass evictions after the 2008 economic crash were less a consequence than a cause of poverty.”

Ms. Cook commented, “It’s been an honor for all of us at Crown to help bring

Evicted into the world. Matt Desmond writes with great heart and intellectual rigor about America’s housing crisis. He follows eight families in Milwaukee as they struggle to keep a roof over their heads, showing us how a lack of stable shelter traps families in poverty and destroys lives meant for better things. Matt often says, ‘We don’t need to outsmart poverty; we need to hate it more.’ With

Evicted, he has helped us do exactly that.”

Evicted previously won the 2016 National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonficiton, the 2017 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction, the 2017 PEN/John Kenneth Galbraith Award for Nonfiction, and the 2016 Discover Great New Writers Award in Nonfiction, among other honors.

History

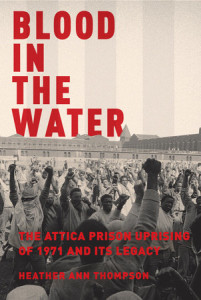

Blood in the Water:

Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy by Heather Ann Thompson.

Edited by Edward Kastenmeier.

Pulitzer citation: “For a narrative history that sets high standards for scholarly judgment and tenacity of inquiry in seeking the truth about the 1971 Attica prison riots.”

Mr. Kastenmeier commented, “Heather is a remarkable historian who has spent the last ten years of her life working diligently to make sure she could do justice to this story before it is too late. She has shown remarkable courage and fortitude in researching a story the authorities didn’t want told. We need that now more than ever. In the years she’s been working on this book the issues it raises have become more urgent than ever. For all these reasons I could not be happier for her upon this news.”

We thank and congratulate Hisham Matar, Colson Whitehead, Matthew Desmond, and Heather Ann Thompson, their respective editors Noah Eaker, Bill Thomas, Amanda Cook, and Edward Kastenmeier, and our colleagues at Random House, Doubleday, Crown Publishers, and Pantheon for continuing and building upon one of our proudest literary traditions.

To view the complete 2017 Pulitzer winners list, click

here.

Learn more about the winners here:

We know readers tend to be writers too, so we feature writing tips from our authors. Who better to offer advice, insight, and inspiration than the authors you admire? They’ll answer several questions about their work, share their go-to techniques and more. Now, get writing!

Did you always want to write? How did you start your career as an author?

Yes. As a child, when people used to ask me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I would say I wanted to be an authoress (that word certainly dates me, doesn’t it?). I used to fill notebooks with stories. When I grew up, of course, I discovered that I needed to eat so became a high school English teacher. Then I got married and had children. There was no time to write. I took a year’s leave of absence following the birth of my third child and worked my way through a suggested Grade XI reading list. It included Georgette Heyer’s Frederica. I was enchanted, perhaps more than I have been with any book before or since. I read everything she had written and then went into mourning because there was nothing else. I decided that I must write books of my own set in the same historical period. I wrote my first Regency (A Masked Deception) longhand at the kitchen table during the evenings and then typed it out and sent it off to a Canadian address I found inside the cover of a Signet Regency romance. It was a distribution centre! However, someone there read it, liked it, and sent in on to New York. Two weeks later I was offered a two-book contract.

What’s the best piece of advice you have received?

Someone (I can’t even remember who) at a convention I attended once advised writers who sometimes sat down to work with a blank mind and no idea how or where to start to write anyway. It sounded absurd, but I have tried it. Nonsense may spill out, but somehow the thought processes get into gear and soon enough I know if what I have written really is nonsense. Sometimes it isn’t. But even if it is, by then I know exactly how I ought to have started, and I delete the nonsense and get going. I have never suffered from writers’ block, but almost every day I sit down with my laptop and a blank mind.

What clichés or bad habits would you tell aspiring writers to avoid? Do you still experience them yourself?

You don’t have to know everything before you start. You don’t have to know the whole plot or every nuance of your characters in great depth. You don’t have to have done exhaustive research. All three things are necessary, but if you wait until you know everything there is to know, you will probably never get started. Get going and the knowledge will come—or at least the knowledge of what exact research you need to do.

Do you ever base characters off people you know? Why or why not?

Never consciously. I wouldn’t want anyone to recognize himself or herself in my books. However, I have spent a longish lifetime living with people and interacting with them and observing them. I like my characters to be authentic, so I suppose I must take all sorts of character traits from people around me. And sometime yes, I suddenly think “Oh, this is so-and-so.”

What are three or four books that influenced your writing, or had a profound affect on you?

All the books of Georgette Heyer would fit here. She was thorough in her research and was awesomely accurate in her portrayal of Georgian and Regency England. At the same time she made those periods her own. She had her own very distinctive voice and vision. When I began to write books set in the same period, I had to learn to do the same thing—to find my own voice and vision so that I was not merely trying to imitate her (something that never works anyway).

Learn more about the book below:

We know readers tend to be writers too, so we feature writing tips from our authors. Who better to offer advice, insight, and inspiration than the authors you admire? They’ll answer several questions about their work, share their go-to techniques and more. Now, get writing!

Is there something you do to get into a writing mood? Somewhere you go or something you do to get thinking?

I find that I do my best work at the beginning of the day, but I’m rarely in a writing mood when I sit down. I’m usually somewhat sleep-deprived, and I always have a long list of other responsibilities calling my name.

But if I can get myself into my chair with a cup of coffee, and start reading the last few days’ work, I find myself making a few changes here and there. Then I’m adding a few new sentences at the end, and before I know it, several hours have passed, I’ve written a few new pages, and I’m in a pretty good mood.

When I fall out of that flow, I get up and go for a walk, make another cup of coffee, and sit back down in my chair, just for another minute or two, and that’s another few hours gone, and some more sentences stacked up to reread tomorrow.

Which is a long way of saying that the best way for me to get into a writing mood is to sit down and start writing. And if I do it every day, it all gets easier.

What’s the best piece of advice you have received?

The painter Chuck Close said, “Amateurs sit and wait for inspiration, the rest of us just get up and go to work.”

He didn’t say it to me, but I consider this good advice for anyone doing creative work. Don’t wait for inspiration. Learn to cultivate it. Write your own writer’s manual. Find the tools and mindset that help you move forward when things get difficult. Because things almost always get difficult. That’s not necessarily a sign that the work is bad, it’s just a part of the process. Learning to understand and manage your own process is, for me, the secret to creative life.

I’m still working on it, by the way. But I’ve found that when I show up and do the work on a daily basis, inspiration will eventually perch on my shoulder and begin to whisper in my ear.

What clichés or bad habits would you tell aspiring writers to avoid? Do you still experience them yourself?

I love the beautiful distractions of the world – television and movies, video games, the internet in general. But I try really hard to avoid them, because they don’t help me become a better writer. They subtract hours from my day. And a writer’s main currency is time. Time to daydream, time to walk and think, time to sit and do the work.

Reading good books is one distraction that will help you become a better writer. And writing – that’s the thing – writing is what will really make you a better writer. Write bad stories until you begin to write so-so stories, which might, if you keep at it, turn to writing good stories. So put down your phone and keep at it.

This is not a new idea, nor one exclusive to writing fiction. The way to get good at playing the piano is to play the piano. And play, play, play.

I tell myself this every day.

What are three or four books that influenced your writing, or had a profound effect on you?

Cormac McCarthy’ Border Trilogy (

All the Pretty Horses,

The Crossing, and

Cities of the Plain) had an enormous influence on me. I love his prose, his use of place as character, and his vivid descriptions of character in action, but the most powerful effect of reading those books was that they freed me up to write about what really interested me. At the most fundamental level, these are cowboy novels. The fact that they also rank among the best of American literature somehow made genre distinctions irrelevant.

Elmore Leonard had a profound influence on me as well. There are a few of his books I really love –

Freaky Deaky,

Stick,

Glitz,

Bandits. But I love his dialogue, his humor, his small-time hustlers, and the economy of his prose. He does a lot with a little, over and over.

The Writer’s Chapbook is a collection of bits and pieces of writers’ interviews culled from

The Paris Review – a long list of great writers. The book is organized by topic, so no matter what problem I’m having, I can find far better writers who’ve had the same problem. It makes me feel better. In addition to dipping in and out, I’ve also read it cover to cover about ten times in the last ten years. I found it used in a clunky old cloth-covered hardback that makes me smile just to hold it in my hand.

Ask me this question next week and I’d probably give you a different list.

Learn more about the book below:

We know readers tend to be writers too, so we feature writing tips from our authors. Who better to offer advice, insight, and inspiration than the authors you admire? They’ll answer several questions about their work, share their go-to techniques and more. Now, get writing!

How would you recommend creating and getting to know your characters?

Marilynne Robinson once told a class that I was in that “all character is just a sense of character.” This feels very true to my experience writing fiction. I don’t actively create my characters; instead, I get a feeling about them, and so I try to chase down this feeling and trap it in a scene in order to spend time with it, and hope that the feeling metamorphosizes into something I can see and understand. I don’t build a character by thinking deliberately about the facts of that person, like what they want, what they look like, what they’re interested in. Those details come later. I know that creating a character profile is a method that works very well for a lot of authors, but when I try to get to know a character, it’s like I’m trying to get to know a shadow cast by someone I can’t see, and maybe never will see, even when the story is finished. And the only way it works for me—the only way—is by building a scene around that shadow, that mere “sense.” But even when a story or novel is finished, I don’t actually ever see my character’s faces. When I think of them, the feeling I get from them is distinct and very, very real, but I don’t picture their facial structures, their hands, their clothes. Though those things are important, they are somewhat meaningless to me as I write; they feel like the only things that I straight-out “create.” In fact, sometimes I forget basic facts and have to go back and check eye color to make sure it’s consistent, or even check the age of my character. Those kinds of facts feel very separate of who the character actually is. There are certain aspects of them I can see. Their stances are often very distinct to me. So are the way their shoes look. The way their voices sound, and the way they speak. And sometimes hair color is clear to me, too, but not always. It’s like when I try to visualize them, they are turning their faces away. They are always in motion. I realized recently that this is how I read, too. When I am invested in a novel, I don’t actually “picture” the people in my head, even if their faces are intricately described. I just feel them. There isn’t really something I can compare this experience to, because there is no experience to me that is anything like reading except for writing. And maybe having a dream, when you have such a strong sense in the morning of what occurred, and it really affects you, but you can’t remember details. The faces are blurred. I don’t know if this is useful or not. I guess what this boils down to is: When you are trying to get to know a character, maybe try not to see them so exactly. Trust your instincts, however fleeting and confusing they may be, and just try to build a scene around a feeling, or rather, let that feeling build the scene for you. It’s the only way my characters ever feel real and honest. I hope this isn’t too ethereal to be useful advice. Of course, there are many ways to get to know your characters, and I think other writers have a much more straightforward time getting to know them. I find it very difficult transcribing feelings into people. I think it’s really hard.

Is there something you do to get into a writing mood? Somewhere you go or something you do to get thinking?

I like to write with animals around. My rabbit has an enormous pen which we built right in front of my window, so I am always looking inside of his pen, watching him and his squirrel visitors. In the morning, before I start writing, I go down to the river and call to my pet ducks. Usually, they fly right to me and have a treat from my hand. I hatched them in an incubator, so they are very tame, even though they have chosen to live in the wild now. When they were little, they would sleep on my lap, or else on my feet, as I worked on my computer. When they decided to fly to the river, I adopted kittens, in part so that I have something to summon onto my lap while I write. Even just having a bird-feeder out my window is very helpful to me. Often, I start by reading beautiful passages by authors I admire. My husband’s office is just on the other side of mine, and often we start out our day by reading to each other what we’d written the day before, to get us going, to get our confidence up. It really helps to have someone pursuing the same things that I am. We help each other a great deal. He always has a cat on his lap, too.

Did you always want to write? How did you start your career as an author?

Yes, I have wanted to write since I was very young. Before I could write, I would often dictate stories or poems to my mom and dad, and they would write them down for me. I remember it seemed like the most magical thing to me, that the things I said could be saved forever simply by my parents making marks on a piece of paper. I was very lucky that I grew up in a house where writing was a natural part of life. My dad is a very prolific writer. Even with all he had to do when I was growing up—teaching, farming, gardening, taking care of children, chopping wood, building barns, managing money trouble—he still found time almost every single day to write, even if he was exhausted. And so it was a very natural part of my existence. I understood writing as a thing that people simply did, a crucial part of daily life. A few years ago, my dad gave me suitcase full of poems. Fifty pounds of poems! I know it’s exactly fifty pounds, because we didn’t want to pay an extra fee at the airport when I was flying these poems from Idaho to Colorado, so we weighed it very carefully and had to remove quite a few to get the weight down. Hauling the suitcase from state to state, whenever I move, makes me feel very sentimental, like I have been given the gift of actually holding the weight of his imagination. Most of the poems are handwritten. Many of them are sonnets. Many of them are very beautiful. Those fifty pounds of poems are my favorite possession. I always wanted to follow in his footsteps, and so I wrote all the time, too. He taught me from a very early age. So I feel like my career never had a starting point. It was always what I was going to do, because it was always what he did.

What clichés or bad habits would you tell aspiring writers to avoid?

I do have a list of cliche’s that I give to my intro-level creative writing students. It’s called “The List.” As a class, we build on it throughout the semester. It’s very long, and I hope students find it funny as well as useful. It was made in good humor. It contains all the themes or situations that I have encountered many times in student writing. Some of the items on the list include: “No coffee shops; no waking up to begin a day; no college or high school parties; no awkward Thanksgivings; no storms that knock out electricity; no hospital beds; no hitmen; no kids kicking cans; no amnesia; no FBI agents; no CEO executives who suddenly quit their jobs and become free-spirits living on the streets playing music; no serial killers; no unwanted pregnancies if the central conflict is whether or not to keep the baby; no camping or hiking stories if the central conflict is getting lost or attacked by a wild animal; no stories whose energy comes entirely from a bitter or sarcastic voice; no grinning. A grin is so much less complicated than a smile.” The list goes on and on. None of these things are absolute, of course. All of them have been written about very, very well. But it is a challenge I like to pose in my writing classes. I think students enjoy it. I hope so. Of course, I break these rules myself sometimes. One of the rules is, “No stories from an animal’s perspective.” And I definitely broke that rule in my novel. Also, my novel has storms knocking out electricity all over the place. And it also contains a hospital bed.

Do you ever base characters off people you know? Why or why not?

Yes and no. My characters are all their own selves, distinct from anyone I’ve met. But I do find that I give my characters many qualities of the people that I love. In my novel, the main characters resemble my family members. Not in their actions, or in their stories, just the sense I get of them. The best parts of my character Wade remind me of my dad. There is a moment in the first chapter when Wade knocks his knuckle on the piano as if to test the quality of its wood, and that moment is my dad exactly. Of course, they are very, very different, too. Similarly, I see my mom in both of my central female characters, Jenny and Ann. This may be a strange thing to say, considering I see my mom as the gentlest person on Earth, and yet I have given some of her kindest qualities to Jenny, who has committed an act of horrifying violence. But lending Jenny some aspects of my mom was a way of empathizing with Jenny, a way of complicating her, a way of loving her in spite of what she’d done, which I felt was very important. And I do love Jenny. I needed to, in order to continue this quite painful story. May, too, was inspired by my sister Mary. This is the closest that I came to writing about someone so directly, though it wasn’t at all my intention. Mary came alive in May so quickly. I have hardly changed a word of the May chapters since their very first draft, because those chapters were almost written for me, by Mary’s childhood voice. I have a photograph of my sister when she is young taking a “swim” in a garbage can filled with water that has been warming in the sun. When I look at that picture, I see both Mary and May, equally. It made writing May’s perspectives both very natural and very painful. I feel May’s loss even more deeply because of her resemblance to my sister. Some parts of the novel, in fact, are painful for me to return to because of that. June, also, reminds me a lot of what I was like when I was young.

What are three or four books that influenced your writing, or had a profound affect on you?

The Progress of Love by Alice Munro, and all of her other books, too. Beloved by Toni Morrison. Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro. Lila by Marilynne Robinson. And Watership Down by Richard Adams.

Learn more about the book below:

But updating a novel set during the early 19th Century has its challenges. For starters, there’s the teeny fact that women can not only inherit both property and money, but can have jobs without being cast out of polite society. When necessary, I borrowed from other Austen novels, and gave my version of Marianne – Jane, in my own novel – depth that would have eluded the original 17-year-old character.

There were challenges, but also pleasures. And it’s the pleasures that are why we revisit Austen’s work so often. Her books are populated with people we know. I’ve met Fanny Dashwoods and Mr. Eltons and Mary Musgroves – we all have. Her stories resonate because they’re inhabited by our own neighbors, parents, and co-workers.

But the familiarity of Austen’s literary world should never be mistaken for simplicity. As I wrote Jane of Austin, I got stuck. A lot. And when I did, I returned to the text. Every time, there was something there. Whether it was a witty line or an insightful scene, I always found something to springboard off of and keep the story rolling.

And that’s the beauty of Austen’s work. There’s always something there. There’s wit and romance on the surface. For the deep thinker, there’s sharp social commentary and character study. And no matter the novel, there’s the pleasure in knowing that there will always, somewhere, be dancing.

Learn about the book here:

But updating a novel set during the early 19th Century has its challenges. For starters, there’s the teeny fact that women can not only inherit both property and money, but can have jobs without being cast out of polite society. When necessary, I borrowed from other Austen novels, and gave my version of Marianne – Jane, in my own novel – depth that would have eluded the original 17-year-old character.

There were challenges, but also pleasures. And it’s the pleasures that are why we revisit Austen’s work so often. Her books are populated with people we know. I’ve met Fanny Dashwoods and Mr. Eltons and Mary Musgroves – we all have. Her stories resonate because they’re inhabited by our own neighbors, parents, and co-workers.

But the familiarity of Austen’s literary world should never be mistaken for simplicity. As I wrote Jane of Austin, I got stuck. A lot. And when I did, I returned to the text. Every time, there was something there. Whether it was a witty line or an insightful scene, I always found something to springboard off of and keep the story rolling.

And that’s the beauty of Austen’s work. There’s always something there. There’s wit and romance on the surface. For the deep thinker, there’s sharp social commentary and character study. And no matter the novel, there’s the pleasure in knowing that there will always, somewhere, be dancing.

Learn about the book here:

The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land in Between by Hisham Matar.

Edited by Noah Eaker.

Pulitzer citation: “For a first-person elegy for home and father that examines with controlled emotion the past and present of an embattled region.”

Susan Kamil, Hisham Matar’s publisher at Random House, said, “It’s thrilling to see Hisham’s work so recognized by the Pulitzer jury. The Return is about Hisham’s personal search for his father, but his art elevates it into a universal quest for justice.”

The Return previously won the inaugural PEN/Jean Stein Book Award.

Fiction

The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land in Between by Hisham Matar.

Edited by Noah Eaker.

Pulitzer citation: “For a first-person elegy for home and father that examines with controlled emotion the past and present of an embattled region.”

Susan Kamil, Hisham Matar’s publisher at Random House, said, “It’s thrilling to see Hisham’s work so recognized by the Pulitzer jury. The Return is about Hisham’s personal search for his father, but his art elevates it into a universal quest for justice.”

The Return previously won the inaugural PEN/Jean Stein Book Award.

Fiction

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead.

Edited by Bill Thomas.

Pulitzer citation: “For a smart melding of realism and allegory that combines the violence of slavery and the drama of escape in a myth that speaks to contemporary America.”

Colson Whitehead commented, “I don’t even know what to say — this has been a crazy ride ever since I handed the book in to my editor. I’m incredibly grateful to everyone who picked up a copy and dug it, and to all the kind folks who championed it along the way — the booksellers, the reviewers, the awesome Oprah Winfrey, and the judges. It’s a nice day to put ‘New York, New York’ on the headphones and walk around city making crazy gestures at strangers.”

The Underground Railroad has sold over 825,000 copies in the United States across all formats. An Oprah’s Book Club 2016 selection, #1 New York Times bestseller, a New York Times Book Review Ten Best Books of 2016 selection and the winner of the 2016 National Book Award for Fiction, the book chronicles young Cora’s journey as she makes a desperate bid for freedom in the antebellum South. After escaping her Georgia plantation for the rumored Underground Railroad, Cora discovers no mere metaphor, but an actual railroad full of engineers and conductors, and a secret network of tracks and tunnels beneath the Southern soil.

General Nonfiction

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead.

Edited by Bill Thomas.

Pulitzer citation: “For a smart melding of realism and allegory that combines the violence of slavery and the drama of escape in a myth that speaks to contemporary America.”

Colson Whitehead commented, “I don’t even know what to say — this has been a crazy ride ever since I handed the book in to my editor. I’m incredibly grateful to everyone who picked up a copy and dug it, and to all the kind folks who championed it along the way — the booksellers, the reviewers, the awesome Oprah Winfrey, and the judges. It’s a nice day to put ‘New York, New York’ on the headphones and walk around city making crazy gestures at strangers.”

The Underground Railroad has sold over 825,000 copies in the United States across all formats. An Oprah’s Book Club 2016 selection, #1 New York Times bestseller, a New York Times Book Review Ten Best Books of 2016 selection and the winner of the 2016 National Book Award for Fiction, the book chronicles young Cora’s journey as she makes a desperate bid for freedom in the antebellum South. After escaping her Georgia plantation for the rumored Underground Railroad, Cora discovers no mere metaphor, but an actual railroad full of engineers and conductors, and a secret network of tracks and tunnels beneath the Southern soil.

General Nonfiction

Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City by Matthew Desmond.

Edited by Amanda Cook.

Pulitzer citation: “For a deeply researched exposé that showed how mass evictions after the 2008 economic crash were less a consequence than a cause of poverty.”

Ms. Cook commented, “It’s been an honor for all of us at Crown to help bring Evicted into the world. Matt Desmond writes with great heart and intellectual rigor about America’s housing crisis. He follows eight families in Milwaukee as they struggle to keep a roof over their heads, showing us how a lack of stable shelter traps families in poverty and destroys lives meant for better things. Matt often says, ‘We don’t need to outsmart poverty; we need to hate it more.’ With Evicted, he has helped us do exactly that.”

Evicted previously won the 2016 National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonficiton, the 2017 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction, the 2017 PEN/John Kenneth Galbraith Award for Nonfiction, and the 2016 Discover Great New Writers Award in Nonfiction, among other honors.

History

Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City by Matthew Desmond.

Edited by Amanda Cook.

Pulitzer citation: “For a deeply researched exposé that showed how mass evictions after the 2008 economic crash were less a consequence than a cause of poverty.”

Ms. Cook commented, “It’s been an honor for all of us at Crown to help bring Evicted into the world. Matt Desmond writes with great heart and intellectual rigor about America’s housing crisis. He follows eight families in Milwaukee as they struggle to keep a roof over their heads, showing us how a lack of stable shelter traps families in poverty and destroys lives meant for better things. Matt often says, ‘We don’t need to outsmart poverty; we need to hate it more.’ With Evicted, he has helped us do exactly that.”

Evicted previously won the 2016 National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonficiton, the 2017 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction, the 2017 PEN/John Kenneth Galbraith Award for Nonfiction, and the 2016 Discover Great New Writers Award in Nonfiction, among other honors.

History

Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy by Heather Ann Thompson.

Edited by Edward Kastenmeier.

Pulitzer citation: “For a narrative history that sets high standards for scholarly judgment and tenacity of inquiry in seeking the truth about the 1971 Attica prison riots.”

Mr. Kastenmeier commented, “Heather is a remarkable historian who has spent the last ten years of her life working diligently to make sure she could do justice to this story before it is too late. She has shown remarkable courage and fortitude in researching a story the authorities didn’t want told. We need that now more than ever. In the years she’s been working on this book the issues it raises have become more urgent than ever. For all these reasons I could not be happier for her upon this news.”

We thank and congratulate Hisham Matar, Colson Whitehead, Matthew Desmond, and Heather Ann Thompson, their respective editors Noah Eaker, Bill Thomas, Amanda Cook, and Edward Kastenmeier, and our colleagues at Random House, Doubleday, Crown Publishers, and Pantheon for continuing and building upon one of our proudest literary traditions.

To view the complete 2017 Pulitzer winners list, click here.

Learn more about the winners here:

Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy by Heather Ann Thompson.

Edited by Edward Kastenmeier.

Pulitzer citation: “For a narrative history that sets high standards for scholarly judgment and tenacity of inquiry in seeking the truth about the 1971 Attica prison riots.”

Mr. Kastenmeier commented, “Heather is a remarkable historian who has spent the last ten years of her life working diligently to make sure she could do justice to this story before it is too late. She has shown remarkable courage and fortitude in researching a story the authorities didn’t want told. We need that now more than ever. In the years she’s been working on this book the issues it raises have become more urgent than ever. For all these reasons I could not be happier for her upon this news.”

We thank and congratulate Hisham Matar, Colson Whitehead, Matthew Desmond, and Heather Ann Thompson, their respective editors Noah Eaker, Bill Thomas, Amanda Cook, and Edward Kastenmeier, and our colleagues at Random House, Doubleday, Crown Publishers, and Pantheon for continuing and building upon one of our proudest literary traditions.

To view the complete 2017 Pulitzer winners list, click here.

Learn more about the winners here: