This article was written by Carolyn Hart and originally appeared on Signature Reads.

This article was written by Carolyn Hart and originally appeared on Signature Reads.

In Ghost on the Case, Bailey Ruth Raeburn, an emissary from Heaven’s Department of Good Intentions, returns to earth to help a young woman who receives a terrifying phone call demanding ransom for her sister. What can Susan Gilbert do? What will she do? What is going to happen to her sister?

My hope is the action scene lures readers to follow Bailey Ruth. I won’t reveal the peaks and valleys in Ghost on the Case to avoid spoiling readers’ enjoyment. Instead, I will illustrate suspense by using the framework of Spooked, a short story that introduces 12-year-old Gretchen Gilman, the protagonist of Letter from Home, my WWII novel from Berkley.

I use the following techniques to create suspense: action, empathy, threat, tension, puzzle, danger, deadline, challenge, and surprise.

Gretchen works in the family café in a small town on Highway 66 in northeastern Oklahoma in the summer of 1943.

Action:

The dust from the convoy rose in plumes. Gretchen stood on tiptoe, waving, waving.

A soldier leaned over the tailgate of the olive drab troop carrier. The blazing July sun touched his crew cut with gold. He grinned as he tossed her a bubble gum. “Chew it for me, kid.”

Empathy: Gretchen turns away, thinking of her brother Jimmy, a Marine in the South Pacific, her mother who works at the B-24 plant in Tulsa, and the troop convoy as she walks toward her grandmother’s café.

She still felt a kind of thrill when she saw the name painted in bright blue: Victory Café… There was a strangeness in the café’s new name. It had been Pfizer’s Café for almost twenty years, but now it didn’t do to be proud of being German…

Empathy and threat: Now the reader has a personal stake in Gretchen, understands there is pain and uncertainty in her life. Her grandmother avoids speaking in the café because of her strong German accent.

In the café, Gretchen sets to work, cleaning, serving food. Customers include Deputy Sheriff Carter. We learn Carter likes to do crossword puzzles and thinks about money. In another booth two military officers from nearby Camp Crowder discuss the Spooklight, a famous and mysterious light that mysteriously appears after dark among the rolling hills. The Army uses night searches for the Spooklight to train troops.

Gretchen’s grandmother brings out a fresh apple pie.

Threat: One of the customers jokingly accuses her of buying sugar on the black market.

“Lotte, the deputy may have to put you in jail if you make any more pies like that.”

Grandmother is upset, explains the pies are made with honey. One of the officers speaks to her in German. The deputy turns hostile.

Tension:

He glowered at Grandmother. “No Heinie talk needed around here . . .”

Gretchen takes trash to an incinerator. As it burns, she climbs a tree. She sees Deputy Carter enter the cemetery. He looks around surreptitiously.

Puzzle:

Back by the pillars, the deputy made one more careful study of the church and the graveyard. He pulled a folded sheet of paper from his pocket and knelt by the west pillar . . . She leaned so far forward her branch creaked.

Danger:

The kneeling man’s head jerked up… The eyes that skittered over the headstones and probed the lengthening shadows were dark and dangerous.

The deputy hides the paper in the pillar. After he leaves, Gretchen finds the paper, reads and replaces it. The message leads her late that night to an abandoned zinc mine. She watches the deputy and a soldier unload an Army truck and hide gasoline tins in the mine.

Deadline: She overhears plans to sell the gasoline Thursday night.

The next day she asks her grandmother what it means when people talk about gasoline on the black market. Lotte explains how important gas is, why it’s rationed, and that even a little bit can make a big difference in the war. Gretchen thinks about her brother fighting in the Pacific. She asks Lotte who catches people in the black market.

Challenge:

“. . . I don’t know,” she said uncertainly.

“I guess in the cities it would be the police. And here it would be the deputy. Or maybe the Army.”

Gretchen thinks about the deputy and about the Army searching for the Spooklight. At the café that afternoon, she asks the young officer if they are still searching for the Spooklight. He says yes and she tells him she’s heard the light has been seen at the old Sister Sue zinc mine.

Gretchen enlists the help of a friend, Millard, whose brother Mike is in the 45

th fighting in Italy. They put pie tins in the trees near the mine to reflect flashlight and draw the soldiers.

Challenge:

. . . she moved out into the clearing. “What’s wrong?”

He was panting. “It’s the Army, but they’re going down the wrong road. . . . They won’t come near enough to see us.”

Surprise:

Suddenly a light burst in the sky . . . Then came another flash and another . . .

Millard lobs lighted clumps of magnesium with his sling shot and draws the Army to the mine where the tins are found, along with a crumpled crossword puzzle in the deputy’s handwriting which Gretchen took from a café booth. The puzzle leads to his arrest and the arrest of a sergeant in the motor pool.

No one ever knew about Millard and Gretchen’s efforts, but Gretchen didn’t mind. The final sentence links the reader to Gretchen:

What really mattered was the gas. Maybe now there would be enough for Jimmy and Mike.

Readers offered action, empathy, threat, tension, puzzle, danger, deadline, challenge, and surprise will keep turning the pages.

Cover detail from

Ghost on the Case by Carolyn Hart

We know readers tend to be writers too, so we feature writing tips from our authors. Who better to offer advice, insight, and inspiration than the authors you admire? They’ll answer several questions about their work, share their go-to techniques and more. Now, get writing!

Did you always want to write? How did you start your career as an author?

Yes. As a child, when people used to ask me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I would say I wanted to be an authoress (that word certainly dates me, doesn’t it?). I used to fill notebooks with stories. When I grew up, of course, I discovered that I needed to eat so became a high school English teacher. Then I got married and had children. There was no time to write. I took a year’s leave of absence following the birth of my third child and worked my way through a suggested Grade XI reading list. It included Georgette Heyer’s Frederica. I was enchanted, perhaps more than I have been with any book before or since. I read everything she had written and then went into mourning because there was nothing else. I decided that I must write books of my own set in the same historical period. I wrote my first Regency (A Masked Deception) longhand at the kitchen table during the evenings and then typed it out and sent it off to a Canadian address I found inside the cover of a Signet Regency romance. It was a distribution centre! However, someone there read it, liked it, and sent in on to New York. Two weeks later I was offered a two-book contract.

What’s the best piece of advice you have received?

Someone (I can’t even remember who) at a convention I attended once advised writers who sometimes sat down to work with a blank mind and no idea how or where to start to write anyway. It sounded absurd, but I have tried it. Nonsense may spill out, but somehow the thought processes get into gear and soon enough I know if what I have written really is nonsense. Sometimes it isn’t. But even if it is, by then I know exactly how I ought to have started, and I delete the nonsense and get going. I have never suffered from writers’ block, but almost every day I sit down with my laptop and a blank mind.

What clichés or bad habits would you tell aspiring writers to avoid? Do you still experience them yourself?

You don’t have to know everything before you start. You don’t have to know the whole plot or every nuance of your characters in great depth. You don’t have to have done exhaustive research. All three things are necessary, but if you wait until you know everything there is to know, you will probably never get started. Get going and the knowledge will come—or at least the knowledge of what exact research you need to do.

Do you ever base characters off people you know? Why or why not?

Never consciously. I wouldn’t want anyone to recognize himself or herself in my books. However, I have spent a longish lifetime living with people and interacting with them and observing them. I like my characters to be authentic, so I suppose I must take all sorts of character traits from people around me. And sometime yes, I suddenly think “Oh, this is so-and-so.”

What are three or four books that influenced your writing, or had a profound affect on you?

All the books of Georgette Heyer would fit here. She was thorough in her research and was awesomely accurate in her portrayal of Georgian and Regency England. At the same time she made those periods her own. She had her own very distinctive voice and vision. When I began to write books set in the same period, I had to learn to do the same thing—to find my own voice and vision so that I was not merely trying to imitate her (something that never works anyway).

Learn more about the book below:

We know readers tend to be writers too, so we feature writing tips from our authors. Who better to offer advice, insight, and inspiration than the authors you admire? They’ll answer several questions about their work, share their go-to techniques and more. Now, get writing!

Is there something you do to get into a writing mood? Somewhere you go or something you do to get thinking?

I find that I do my best work at the beginning of the day, but I’m rarely in a writing mood when I sit down. I’m usually somewhat sleep-deprived, and I always have a long list of other responsibilities calling my name.

But if I can get myself into my chair with a cup of coffee, and start reading the last few days’ work, I find myself making a few changes here and there. Then I’m adding a few new sentences at the end, and before I know it, several hours have passed, I’ve written a few new pages, and I’m in a pretty good mood.

When I fall out of that flow, I get up and go for a walk, make another cup of coffee, and sit back down in my chair, just for another minute or two, and that’s another few hours gone, and some more sentences stacked up to reread tomorrow.

Which is a long way of saying that the best way for me to get into a writing mood is to sit down and start writing. And if I do it every day, it all gets easier.

What’s the best piece of advice you have received?

The painter Chuck Close said, “Amateurs sit and wait for inspiration, the rest of us just get up and go to work.”

He didn’t say it to me, but I consider this good advice for anyone doing creative work. Don’t wait for inspiration. Learn to cultivate it. Write your own writer’s manual. Find the tools and mindset that help you move forward when things get difficult. Because things almost always get difficult. That’s not necessarily a sign that the work is bad, it’s just a part of the process. Learning to understand and manage your own process is, for me, the secret to creative life.

I’m still working on it, by the way. But I’ve found that when I show up and do the work on a daily basis, inspiration will eventually perch on my shoulder and begin to whisper in my ear.

What clichés or bad habits would you tell aspiring writers to avoid? Do you still experience them yourself?

I love the beautiful distractions of the world – television and movies, video games, the internet in general. But I try really hard to avoid them, because they don’t help me become a better writer. They subtract hours from my day. And a writer’s main currency is time. Time to daydream, time to walk and think, time to sit and do the work.

Reading good books is one distraction that will help you become a better writer. And writing – that’s the thing – writing is what will really make you a better writer. Write bad stories until you begin to write so-so stories, which might, if you keep at it, turn to writing good stories. So put down your phone and keep at it.

This is not a new idea, nor one exclusive to writing fiction. The way to get good at playing the piano is to play the piano. And play, play, play.

I tell myself this every day.

What are three or four books that influenced your writing, or had a profound effect on you?

Cormac McCarthy’ Border Trilogy (

All the Pretty Horses,

The Crossing, and

Cities of the Plain) had an enormous influence on me. I love his prose, his use of place as character, and his vivid descriptions of character in action, but the most powerful effect of reading those books was that they freed me up to write about what really interested me. At the most fundamental level, these are cowboy novels. The fact that they also rank among the best of American literature somehow made genre distinctions irrelevant.

Elmore Leonard had a profound influence on me as well. There are a few of his books I really love –

Freaky Deaky,

Stick,

Glitz,

Bandits. But I love his dialogue, his humor, his small-time hustlers, and the economy of his prose. He does a lot with a little, over and over.

The Writer’s Chapbook is a collection of bits and pieces of writers’ interviews culled from

The Paris Review – a long list of great writers. The book is organized by topic, so no matter what problem I’m having, I can find far better writers who’ve had the same problem. It makes me feel better. In addition to dipping in and out, I’ve also read it cover to cover about ten times in the last ten years. I found it used in a clunky old cloth-covered hardback that makes me smile just to hold it in my hand.

Ask me this question next week and I’d probably give you a different list.

Learn more about the book below:

We know readers tend to be writers too, so we feature writing tips from our authors. Who better to offer advice, insight, and inspiration than the authors you admire? They’ll answer several questions about their work, share their go-to techniques and more. Now, get writing!

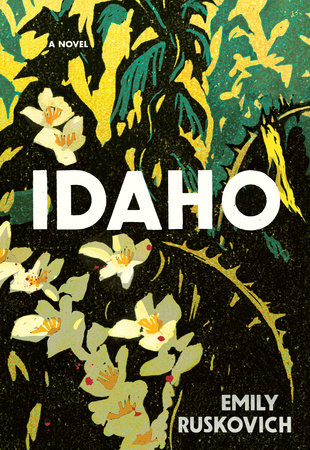

How would you recommend creating and getting to know your characters?

Marilynne Robinson once told a class that I was in that “all character is just a sense of character.” This feels very true to my experience writing fiction. I don’t actively create my characters; instead, I get a feeling about them, and so I try to chase down this feeling and trap it in a scene in order to spend time with it, and hope that the feeling metamorphosizes into something I can see and understand. I don’t build a character by thinking deliberately about the facts of that person, like what they want, what they look like, what they’re interested in. Those details come later. I know that creating a character profile is a method that works very well for a lot of authors, but when I try to get to know a character, it’s like I’m trying to get to know a shadow cast by someone I can’t see, and maybe never will see, even when the story is finished. And the only way it works for me—the only way—is by building a scene around that shadow, that mere “sense.” But even when a story or novel is finished, I don’t actually ever see my character’s faces. When I think of them, the feeling I get from them is distinct and very, very real, but I don’t picture their facial structures, their hands, their clothes. Though those things are important, they are somewhat meaningless to me as I write; they feel like the only things that I straight-out “create.” In fact, sometimes I forget basic facts and have to go back and check eye color to make sure it’s consistent, or even check the age of my character. Those kinds of facts feel very separate of who the character actually is. There are certain aspects of them I can see. Their stances are often very distinct to me. So are the way their shoes look. The way their voices sound, and the way they speak. And sometimes hair color is clear to me, too, but not always. It’s like when I try to visualize them, they are turning their faces away. They are always in motion. I realized recently that this is how I read, too. When I am invested in a novel, I don’t actually “picture” the people in my head, even if their faces are intricately described. I just feel them. There isn’t really something I can compare this experience to, because there is no experience to me that is anything like reading except for writing. And maybe having a dream, when you have such a strong sense in the morning of what occurred, and it really affects you, but you can’t remember details. The faces are blurred. I don’t know if this is useful or not. I guess what this boils down to is: When you are trying to get to know a character, maybe try not to see them so exactly. Trust your instincts, however fleeting and confusing they may be, and just try to build a scene around a feeling, or rather, let that feeling build the scene for you. It’s the only way my characters ever feel real and honest. I hope this isn’t too ethereal to be useful advice. Of course, there are many ways to get to know your characters, and I think other writers have a much more straightforward time getting to know them. I find it very difficult transcribing feelings into people. I think it’s really hard.

Is there something you do to get into a writing mood? Somewhere you go or something you do to get thinking?

I like to write with animals around. My rabbit has an enormous pen which we built right in front of my window, so I am always looking inside of his pen, watching him and his squirrel visitors. In the morning, before I start writing, I go down to the river and call to my pet ducks. Usually, they fly right to me and have a treat from my hand. I hatched them in an incubator, so they are very tame, even though they have chosen to live in the wild now. When they were little, they would sleep on my lap, or else on my feet, as I worked on my computer. When they decided to fly to the river, I adopted kittens, in part so that I have something to summon onto my lap while I write. Even just having a bird-feeder out my window is very helpful to me. Often, I start by reading beautiful passages by authors I admire. My husband’s office is just on the other side of mine, and often we start out our day by reading to each other what we’d written the day before, to get us going, to get our confidence up. It really helps to have someone pursuing the same things that I am. We help each other a great deal. He always has a cat on his lap, too.

Did you always want to write? How did you start your career as an author?

Yes, I have wanted to write since I was very young. Before I could write, I would often dictate stories or poems to my mom and dad, and they would write them down for me. I remember it seemed like the most magical thing to me, that the things I said could be saved forever simply by my parents making marks on a piece of paper. I was very lucky that I grew up in a house where writing was a natural part of life. My dad is a very prolific writer. Even with all he had to do when I was growing up—teaching, farming, gardening, taking care of children, chopping wood, building barns, managing money trouble—he still found time almost every single day to write, even if he was exhausted. And so it was a very natural part of my existence. I understood writing as a thing that people simply did, a crucial part of daily life. A few years ago, my dad gave me suitcase full of poems. Fifty pounds of poems! I know it’s exactly fifty pounds, because we didn’t want to pay an extra fee at the airport when I was flying these poems from Idaho to Colorado, so we weighed it very carefully and had to remove quite a few to get the weight down. Hauling the suitcase from state to state, whenever I move, makes me feel very sentimental, like I have been given the gift of actually holding the weight of his imagination. Most of the poems are handwritten. Many of them are sonnets. Many of them are very beautiful. Those fifty pounds of poems are my favorite possession. I always wanted to follow in his footsteps, and so I wrote all the time, too. He taught me from a very early age. So I feel like my career never had a starting point. It was always what I was going to do, because it was always what he did.

What clichés or bad habits would you tell aspiring writers to avoid?

I do have a list of cliche’s that I give to my intro-level creative writing students. It’s called “The List.” As a class, we build on it throughout the semester. It’s very long, and I hope students find it funny as well as useful. It was made in good humor. It contains all the themes or situations that I have encountered many times in student writing. Some of the items on the list include: “No coffee shops; no waking up to begin a day; no college or high school parties; no awkward Thanksgivings; no storms that knock out electricity; no hospital beds; no hitmen; no kids kicking cans; no amnesia; no FBI agents; no CEO executives who suddenly quit their jobs and become free-spirits living on the streets playing music; no serial killers; no unwanted pregnancies if the central conflict is whether or not to keep the baby; no camping or hiking stories if the central conflict is getting lost or attacked by a wild animal; no stories whose energy comes entirely from a bitter or sarcastic voice; no grinning. A grin is so much less complicated than a smile.” The list goes on and on. None of these things are absolute, of course. All of them have been written about very, very well. But it is a challenge I like to pose in my writing classes. I think students enjoy it. I hope so. Of course, I break these rules myself sometimes. One of the rules is, “No stories from an animal’s perspective.” And I definitely broke that rule in my novel. Also, my novel has storms knocking out electricity all over the place. And it also contains a hospital bed.

Do you ever base characters off people you know? Why or why not?

Yes and no. My characters are all their own selves, distinct from anyone I’ve met. But I do find that I give my characters many qualities of the people that I love. In my novel, the main characters resemble my family members. Not in their actions, or in their stories, just the sense I get of them. The best parts of my character Wade remind me of my dad. There is a moment in the first chapter when Wade knocks his knuckle on the piano as if to test the quality of its wood, and that moment is my dad exactly. Of course, they are very, very different, too. Similarly, I see my mom in both of my central female characters, Jenny and Ann. This may be a strange thing to say, considering I see my mom as the gentlest person on Earth, and yet I have given some of her kindest qualities to Jenny, who has committed an act of horrifying violence. But lending Jenny some aspects of my mom was a way of empathizing with Jenny, a way of complicating her, a way of loving her in spite of what she’d done, which I felt was very important. And I do love Jenny. I needed to, in order to continue this quite painful story. May, too, was inspired by my sister Mary. This is the closest that I came to writing about someone so directly, though it wasn’t at all my intention. Mary came alive in May so quickly. I have hardly changed a word of the May chapters since their very first draft, because those chapters were almost written for me, by Mary’s childhood voice. I have a photograph of my sister when she is young taking a “swim” in a garbage can filled with water that has been warming in the sun. When I look at that picture, I see both Mary and May, equally. It made writing May’s perspectives both very natural and very painful. I feel May’s loss even more deeply because of her resemblance to my sister. Some parts of the novel, in fact, are painful for me to return to because of that. June, also, reminds me a lot of what I was like when I was young.

What are three or four books that influenced your writing, or had a profound affect on you?

The Progress of Love by Alice Munro, and all of her other books, too. Beloved by Toni Morrison. Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro. Lila by Marilynne Robinson. And Watership Down by Richard Adams.

Learn more about the book below:

We know readers tend to be writers too, so we feature writing tips from our authors. Who better to offer advice, insight, and inspiration than the authors you admire? They’ll answer several questions about their work, share their go-to techniques and more. Now, get writing!

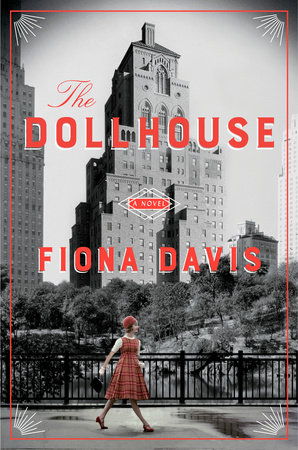

How would you recommend creating and getting to know your characters?

The most important task is to figure out what your characters’ goals, history and personality quirks are – what they most want from life, and why. And for characters who live in an earlier time period, there’s the additional task of conveying what life was like back then. Since part of my book takes place in the early 1950s, I headed to the library and read old newspapers and magazines, scrutinizing the advertisements as well as the articles. I also listened to the music of the time period, from bebop to Rosemary Clooney, to get a sense of popular trends.

Is there something you do to get into a writing mood? Somewhere you go or something you do to get thinking?

The Met Museum in New York City is a great place to be inspired. I was lucky enough to catch the designer Charles James’s exhibit while working on

The Dollhouse, and the fabrics and styles perfectly captured the essence of 1950s fashion. A run around the reservoir in Central Park can be helpful when I’m trying to solve a plotting problem or visualize an upcoming scene. I find I procrastinate for a good hour before getting down to the actual business of writing. This can include doing laundry, checking email, and reading the paper, until the guilt becomes inescapable. But once I start, I fall into that state of flow and become unaware of time passing. I love that feeling.

Did you always want to write? How did you start your career as an author?

I got a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University, which taught me how to research and do interviews and write on deadline, and all those skills transferred over to writing fiction. When you’re used to writing every day, it’s easy to power through the painful moments of the first draft, knowing you can clean it up later. The process isn’t precious, it’s just work.

What clichés or bad habits would you tell aspiring writers to avoid? Do you still experience them yourself?

I have a Post-it on the bulletin board above my desk with the heading “Bad Words” written on it: these include “realized, wondered, felt, saw, thought, and heard.” Once I’m done with the first draft, I search for each bad word and instead use deep point of view. (For example, replacing “She heard the cat meow,” with “The cat meowed.”) Makes the writing simpler and more powerful. Luckily, I’ve gotten to the point where I usually catch myself before using them, but you can never be too sure.

What are three or four books that influenced your writing, or had a profound effect on you?

The Perfume Collector by Kathleen Tessaro is set in two decades, the 1950s and the 1920s, and her attention to detail and descriptions are breathtaking.

The Lottery by

Shirley Jackson, published in 1948, is eerily timeless, as is

People of the Book by

Geraldine Brooks. I swear Brooks traveled back in time to write that one, it’s so rich in setting and character. In high school, I had a teacher who instilled an early love of

Shakespeare, and the musicality of

Macbeth definitely stuck with me.

Learn more about the book below:

We know readers tend to be writers too, so we feature writing tips from our authors. Who better to offer advice, insight, and inspiration than the authors you admire? They’ll answer several questions about their work, share their go-to techniques and more. Now, get writing!

How would you recommend creating and getting to know your characters?

The absolute first thing I do is decide my main characters’ names. I feel like I need to know someone’s name before I can start to know him or her. My favorite place to figure out first names is the Social Security popular baby names website, where you can view name popularity by birth year (back to 1879) to see what common and (uncommon) names were in the year your character was born.

After I decide names, I’ll start to make notes of other things, like birthdays/age or relationships to other characters, quirks, where a character lives, or things he/she likes or dislikes. But I start drafting pretty soon into this process. I mostly learn and get to really know my characters as I’m writing the first draft, thinking about what they do and how they react and speak when I put them in different situations. So I think the best way I get to know my characters is to write them. By the time I get to the end of the first draft, they’re often different than what I started with (and I know them much better). But then I go back and revise.

After developing an idea, what is the first action you take when beginning to write?

The first line of novel is really important. It sets the tone for the entire book. I want it to show what the book is ultimately about, but also to be interesting and hook the reader. When I first start thinking about and developing an idea I always start thinking about first lines. I jot down ideas, often for weeks or months. But, I don’t wait for the perfect first line before I start drafting a book. I begin with the first one that comes to me and then I keep writing from there to get my first draft going. So just the act of getting words and ideas down on the page is the most important action I take in order to actually start writing. I set a goal for myself – usually 3-5 pages a day – and I make myself sit down and write something, make some progress in the draft, even if it’s ultimately terrible and will all be changed in revision.

Most of the time the first line that appears in the final draft of the book is not at all what I started with. I keep thinking on that first line, even as I keep writing the first draft. Usually I don’t understand enough about the story myself until I finish or get most of the way through a first draft. So I start writing at the beginning, but 9 times out of 10 that beginning changes by the time I make it to the end!

Is there something you do to get into a writing mood? Somewhere you go or something you do to get thinking?

I always write at home, and I need quiet to write. I negotiate my writing schedule around my kids’ schedules so I usually write while my kids are at school during weekdays, or very early in the mornings on the weekends or during the summer when my kids are home – really, whenever I can find uninterrupted quiet each day. I have an office in my house where I can shut the door, and I do write there, but when no one else is home I also write at my kitchen table.

I like to drink coffee while I write, and that always helps to get me thinking. Or when I get stuck, I’ll exercise. Taking a long walk, run, or hike, often helps me work through a plot a point I was stuck on or figure out a problem in my story.

What’s the best piece of advice you have received?

The best advice, and I got this from a writing professor in grad school, is simply, “butt in chair.” As in, just sit down and force yourself to write something, no matter what it is or how terrible you think it is. The hardest part is making yourself sit down to do it. So I don’t let myself make excuses – I put my butt in the chair every morning and write something.

What are three or four books that influenced your writing, or had a profound effect on you?

I read

Bird By Bird by

Anne Lamott in the first fiction writing class I took, and I still have a copy on the shelf in my office. I love what she writes about first drafts and I feel like it’s still important to give myself permission to write something terrible the first time around as long as I write

something. I’m a big believer in the importance of revision!

Black and Blue by

Anna Quindlen is one of my favorite novels, and the first I read by her. I come back to it, and her novels, again and again, because I feel like I learn so much about sympathetic character development from her.

The Handmaid’s Tale by

Margaret Atwood, which I first read in college, always makes me think about writing characters in a world different from our own today (which is applicable for writing historical fiction as well) and the fact that characters still need to first be inherently human and relatable, no matter how different their world is from the one we know.

Learn more about the book below!

We know readers tend to be writers too, so we feature writing tips from our authors. Who better to offer advice, insight, and inspiration than the authors you admire? They’ll answer several questions about their work, share their go-to techniques and more. Now, get writing!

What writing techniques have you found most important or memorable?

What matters most, I think, is not technique but feeling—the emotions with which we write. Writing an early draft, we have to let go, forget caution and embarrassment, confront trouble. Much of my writing time is spent getting into the frame of mind in which that’s possible. We all have different ways.

To revise, we need to ask the kind of obvious questions we ask in the rest of life. “This thing I wrote—does it make sense? Is it clear? Does it get boring?” There are no rules. Some pages and paragraphs and sentences will be good, some won’t. Much of the technique consists of

not treating writing as something with a special technique, treating it more like other things we manage to do, though we may not look very professional doing them—cooking a meal or getting ready to have people over. Writing is like that: sloppy, haphazard, but manageable if we work hard but don’t take it too seriously.

Do you ever base characters off people you know? Why or why not?

I wish I could say that I

never base characters on real people! I believe in the imagination! And generally I don’t start with someone real. I think of a situation—maybe “a woman on a wooden pier waiting to be picked up by a boat.” I try to glean what’s happening, and who she is. It’s a wobbly old pier, so she can’t pace comfortably, and she’s new to this kind of place. . . . She’s barefoot, and just got a splinter, and somehow that suggests her job teaching kindergarten and her cousin the cop. . . and is he the person coming in the boat? And who’s with him? I make up characters and stories the way we bring back lost memories, detail by detail. But Grace Paley says somewhere that all her characters are invented except the father, who is her father. And I’ve found myself putting pieces of my father into a couple of novels. Not all of him, and the characters also have traits he didn’t have. Aspects of my father. I don’t know why.

After developing an idea, what is the first action you take when beginning to write?

I envy the courage of writers who put random thoughts on pages for months

without an idea. They trust that their unconscious minds will eventually disgorge one, when the act of writing or typing lulls them into saying what’s most important to them. These writers suffer more than the rest of us, and have false starts, but eventually their work may be more authentic.

I have been known to begin a story that way, but for a novel, I wait for an idea, and make notes. But then I go someplace where I can be my uncensored self (not my desk, where business occurs) and write nothing until a word I don’t expect comes out of nowhere. After all, what’s hardest about starting anything new is to keep from writing what you expected to write. I too believe in letting the unconscious mind give us new thoughts when we’re drowsy and irresponsible—but I make it a little easier by having some notion of where I’m going.

What are three or four books that influenced your writing, or had a profound effect on you?

The short stories in Tillie Olsen’s

Tell Me a Riddle and Grace Paley’s

The Little Disturbances of Man and

Enormous Changes at the Last Minute made me think I could try writing short stories: they were about ordinary people, people in messy cities like those I knew, people from immigrant families, as I am.

Jane Austen’s

Emma is about a young woman with many flaws whom we like anyway, and E.M. Forster’s

Howards End is about a personal connection between two women—sisters—that is so nuanced and strong that it enables them to fix their lives when the world of “telegrams and anger” has made trouble for them. That’s what I want to write about: ordinary people, flawed people, people with intense inner lives for whom emotional connection can make a practical difference—who can do what they need to do because they understand each other.

Learn more about the book below:

This article was written by Jennie Yabroff and originally appeared on Signature Reads.

This article was written by Jennie Yabroff and originally appeared on Signature Reads.

If, as Oliver Kamm writes in his new book Accidence Will Happen, “learning rules of language is part of what it is to be human,” then arguing over what those rules are, and if they matter, is most certainly another part. Can you start a sentence with ‘hopefully?’ Is confusing ‘it’s’ and ‘its’ an unpardonable offense, or no big deal? And is it ever OK to use the plural pronoun ‘their’ when you’re referring to a single person? (And what about starting a sentence with and?) Today, people who have strong opinions about the answers to these questions (a small but passionate minority) fall into two groups: pedants and permissives, or, as Kamm differentiates them, prescriptivists and descriptivists.

Kamm, who writes about grammar and usage for the London

Times, calls himself a ‘recovering pedant’ who believes much of our insistence on set rules for English is really a cover for snobbery and exclusivism. Yet he is not above correcting others who have written similar books, especially the sticklers, who, he claims, “are confused about what grammar is,” (and who would probably suggest he rephrase his sentence so as not to end with the prepositional-sounding ‘is’).

Grammar, he points out, refers to syntax, morphology (the way words are formed), and phonology (the way words sound). Sticklers, he writes, often confuse grammar for orthology (spelling and punctuation). Whenever one of these purists publishes a book, armchair grammarians (and orthologists) take great glee in pointing out the errors in the text (many of which, to be fair, are merely typos that slipped past the eye of wearied copyeditors).

To figure out which side of the great debate you fall on (if you think that sentence should read, ‘to figure out upon which side you fall,’ you already know the answer), check out these other guides to the confounding, complicated, and fascinating language known as modern English.

Eats, Shoots and Leaves by Lynne Truss

Eats, Shoots and Leaves by Lynne Truss

Truss, the author of several guides to punctuation, comes down firmly on the side of the sticklers (and earns Kamm’s wrath for her punctiliousness). As the title of her book proves, a misplaced or missing comma (or apostrophe, or hyphen) radically alters the meaning of sentences, turning the dietary habits of a panda bear into a description of a gun-bearing mammal who dines, opens fire, then departs.

Between You and Me by Mary Norris

The New Yorker

Between You and Me by Mary Norris

The New Yorker is as famous for its exacting copyediting process as it is for the peccadillos of certain editors such as William Shawn, who forbade words including ‘workaholic,’ ‘balding,’ and ‘urinal.’ This memoir by Norris, who has worked at the magazine since 1978, was an unlikely hit, and spawned an online video series where she reveals the grammar errors she’s found in writers’ drafts, and describes not just why they’re wrong, but how to fix them.

Elements of Style (Illustrated) by William Strunk, Jr., E.B. White, and Maira Kalman

Elements of Style (Illustrated) by William Strunk, Jr., E.B. White, and Maira Kalman

If grammar has a Bible, it is this book. First published in 1918, when the world was in need of some solid, straightforward guidance, this book remains beloved for its no-nonsense tone and unapologetic belief that the rules of grammar do exist, and are actually quite easy to follow, if you just pay attention when you speak and write. This edition, lovingly illustrated by Maira Kalman, injects the book with a playful visual guide to the etiquette of proper sentence construction.

Yes, I Could Care Less by Bill Walsh

Yes, I Could Care Less by Bill Walsh

The problem with the way most of us speak and write, the author of this book contends, is we forget to consult our brains. A longtime copyeditor for the

Washington Post, Walsh is happy to hold the unpopular opinion that there is a right and wrong way to use words, and it actually matters if we say ‘literally’ when we mean ‘figuratively’ or claim we ‘could care less’ when in fact we mean the opposite. Walsh himself cares, quite a bit, and isn’t afraid to stand up for what he believes.

Image ©

flickr

We know readers tend to be writers too, so we feature writing tips from our authors. Who better to offer advice, insight, and inspiration than the authors you admire? They’ll answer several questions about their work, share their go-to techniques and more. Now, get writing!

Is there something you do to get into a writing mood? Somewhere you go or something you do?

Yes, I go to my “office” in the backyard, a former garden shed that I fixed up when we bought the house we’re living in now (unfortunately, I have a difficult time blocking out the world, so writing in a “public” place is impossible for me). There is no phone or internet, just a table and chair and some reference books along with a laptop and a typewriter. The first thing I do to get started is pour a cup of coffee from a thermos and light a cigarette. Believe me, I’ve tried, but I can’t do it any other way.

What’s the best piece of advice you ever received?

Learn to sit in the chair for a designated period of time, regardless of whether anything is “happening” or not. I think this is the main thing that defeats many aspiring writers, and it’s easy for me to see why. There have been many, many days when I’d rather be doing anything else (it’s the only time when washing windows seems like a fantastic idea). But I

almost always force myself to stay put because nothing will ever happen unless I’m sitting there to help make it happen. It might be a little easier for me because I’m the type of person who does better at writing and everything else if I’m living on a schedule, but it’s still hard sometimes.

What writing techniques have you found most important?

When I decided to learn how to write short stories, I didn’t know anything and I struggled for quite a while without making much progress. Then I read an interview with a writer who said she learned to write by copying out other people’s stuff. For some reason, that made sense to me, and I began typing out short stories by Hemingway, Cheever, Yates, Johnson, O’Connor, on and on. I did approximately one story a week for maybe 18 months and it got me so much “closer” to seeing how they did things like writing dialogue, making transitions, etc. It could be that it worked for me because I’m not a very good reader, but it definitely helped me start figuring some things out. On occasion, when I’m having a bad day, I will still type out a paragraph or two from somebody else.

What are three or four books that influenced your writing, or had a profound effect on you?

Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy is the best novel I’ve ever read. Unfortunately, reading it also makes me realize how worthless my own work is. Denis Johnson’s

Jesus’ Son. I copied every story out of that book when I was starting out, and it helped push me toward the idea of developing, for lack of a better term, my own “voice.” Also, Earl Thompson’s

A Garden of Sand, which I came across when I was maybe sixteen and have never forgotten. I’ve mentioned it before in interviews as being the first book I ever read that contained characters similar to some of the people I grew up around. Of course, you have to understand, my reading was somewhat limited in those days and I probably hadn’t even heard of people like Faulkner and O’Connor yet.

Learn more about the book below:

This article was written by Carolyn Hart and originally appeared on Signature Reads.

This article was written by Carolyn Hart and originally appeared on Signature Reads.

Eats, Shoots and Leaves

Eats, Shoots and Leaves