Tag Archives: editing

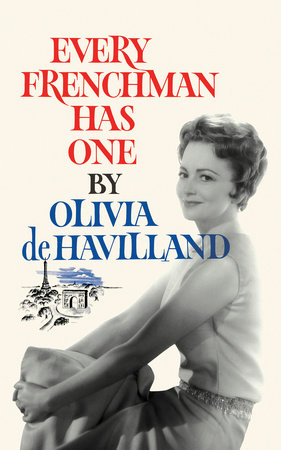

From the Editor’s Desk: Matt Inman, Senior Editor for Crown Trade on Every Frenchman Has One by Olivia de Havilland

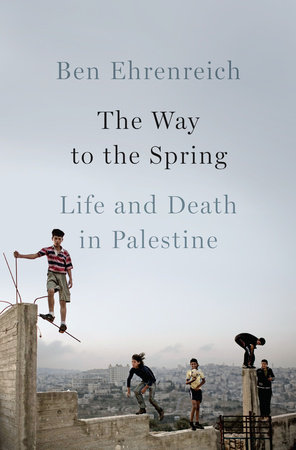

From the Editor’s Desk: Scott Moyer, VP & Publisher of the Penguin Press on The Way to the Spring by Ben Ehrenreich

To publish a book about Palestinian lives in the West Bank is to take part in a fiercely contested debate, whether you like it or not. It’s a debate that’s become a dialogue of the deaf, and it can seem too complicated and unpleasant to pay too much attention to. I didn’t come to this book out of some sense of advocacy, in particular, nor frankly would I have wanted to: there are enough shrilly partisan books out there, for the most part preaching to the choir. But what I did and do feel, stubbornly, is that nothing human should be alien to us, and that if a great journalist, which is to say a great observer and listener, someone with a great head and heart, really goes there and stays there, then we ought to pay attention. And Ben Ehrenreich is a great journalist. The contact high from his talent is exhilarating.

He’s also very brave. Show us the extreme challenges of life in a public housing project in the South Bronx, or in a Mumbai slum, and it’s all good; you get roses thrown at your feet. But the West Bank is under Israeli military occupation, of course, and has been for a very long time, and so if you write a clear and honest human account of life for ordinary Palestinians, then you can be accused of being “anti-Israel” , or worse, and you find yourself under assault, or at least greeted with uncomfortable silence. In fact, Ben Ehrenreich is no more anti-Israel than someone writing about life in Northern Ireland under British occupation was by definition anti-English. If you bring to light stories that depict inhumane situations, and thereby create pressure to improve them, are you “anti” the country in which the inhumane situations exist or “pro” that country?

Anyway, I am making this book sound shrill itself, which is precisely what it is not. Under the spell of the storytelling, we find ourselves in the shoes of a group of wonderfully vivid and disparate characters, united by the struggle to live decent lives. What I think was most shocking to me was how openly the enemies of the Palestinian presence in the West Bank – the far right-wing Israeli settlers – admit to having an eliminationism agenda: their stated goal is to drive all Palestinians out of the West Bank and take it over completely – ethnic cleansing on the installment plan. And their means of achieving that is to make life unbearable for the Palestinians.

Ben Ehrenreich is a powerful witness to all this; he spent several years in the West Bank, all told, and came to know these communities intimately. There’s sadness and heartbreak in this book, but there’s also laughter and affirmation. But there’s no escaping the fact that this shows us a situation that has become very extreme, even almost unimaginable, and so I think however uncomfortable it makes us, it’s worth our whole-hearted support. This isn’t a dogged or prescriptive polemic, it is a work of art; by immersing us in these lives, these stories, it places us as readers right on the horns of the dilemma. There’s no easy way out, for anyone, but the more we bring this world into our consciousness, the more human we will be – and the more honest we will be with each other about the consequences of our own inaction.

Learn more about The Way to the Spring below:

From the Editor’s Desk: Peter Gethers, President, Random House Studio and Senior Vice President, Editor at Large Penguin Random House on Sweetbitter by Stephanie Danler

From the Editor’s Desk: Jake Morrissey, Executive Editor, on Three-Martini Lunch by Suzanne Rindell

The Life of a Book: An interview with editor Brant Rumble, Part 2

Q: Do you have a favorite part of the editorial and publishing process?

A: I have a few. First, there’s the moment when you realize that you want to work on a book. It’s not unlike the beginning of a romance, minus all of the untoward activities, of course. Then there’s the editing. It’s definitely work, and sometimes it’s more work than anticipated, but, when you can shut out the world and really interact with what someone has written—ask them more questions, challenge them a bit, and just enjoy it like any reader would—that’s entertaining. It’s a heightened form of reading. And, last but not least, there are moments when you can tell that a reader (other than yourself) has genuinely loved a book. Whether it’s a rave review or a crowd of people at an author’s event who are obviously enjoying themselves, or someone on the subway reading one of your books with an intent (but not displeased) look on his or her face. I have a cynical side, like anyone else, but those are the things that have a way of eroding it, at least until the next moment of pain and disappointment comes along.

Q: Do you have a favorite part of the editorial and publishing process?

A: I have a few. First, there’s the moment when you realize that you want to work on a book. It’s not unlike the beginning of a romance, minus all of the untoward activities, of course. Then there’s the editing. It’s definitely work, and sometimes it’s more work than anticipated, but, when you can shut out the world and really interact with what someone has written—ask them more questions, challenge them a bit, and just enjoy it like any reader would—that’s entertaining. It’s a heightened form of reading. And, last but not least, there are moments when you can tell that a reader (other than yourself) has genuinely loved a book. Whether it’s a rave review or a crowd of people at an author’s event who are obviously enjoying themselves, or someone on the subway reading one of your books with an intent (but not displeased) look on his or her face. I have a cynical side, like anyone else, but those are the things that have a way of eroding it, at least until the next moment of pain and disappointment comes along.

Q: Do you have a favorite section or quote from But What if We’re Wrong?

Q: Do you have a favorite section or quote from But What if We’re Wrong?

A: More than any of the other nonfiction books that Chuck has written, this one is all of a piece. I think Chuck’s reader have gotten used to reading his books like collections, reading some essays, but not others, and sometimes not in sequential order. Which is fine. But not for this book. It builds. The chapter on music is the first chapter I read because it was the first chapter draft Chuck shared with me. I enjoyed it, but I know now that I didn’t fully get it, and that’s because I wasn’t reading it in the context of the book. (The chapter begins on page 59.) My early impression became problematic when I expressed some vague concerns about the piece, which I think alarmed Chuck, because—for anyone who knows me—music is my primary preoccupation, and, if I don’t love reading something that a writer I enjoy reading has written about music, then there might actually be something amiss. But the only issue was that I wasn’t reading the material within the flow of the book. Now the music chapter is definitely among my favorites, and, having said all of this, I’m sure the chapter will be excerpted somewhere, and therefore read in isolation. I’m not too worried. I look forward to seeing how readers react to it. The chapter about TV is a challenging one. Chuck makes an argument that I have a hard time understanding, or “buying” as some people like to put it. But that’s why I like it. I don’t just read books to agree with them. Towards the end of the book, there’s a significant riff on the phrase “you’re doing it wrong” that sums up quite a lot about the problem of our collective experience at this point in human history.

The Life of a Book: An interview with editor Brant Rumble, Part 1

Q: How would you describe this book to someone who’s never read Chuck?

A: Imagine you’re about to meet up at a bar (or any other kind of location where you can relax and enjoy yourself) with several of your best friends. You’re going to discuss both important and completely unimportant subjects. You’re going to play some songs on the jukebox, which might lead you to ponder the career of Gerry Rafferty. You’re going to casually watch whatever games are on. You’ll argue, you’ll laugh—both with and at each other—and you might be surprised by a good friend’s revelation or news. And, unless someone loses a tooth or a credit card, you’ll have a good time, living in a world where not all times are good.

Reading Chuck is the literary equivalent of that night out. There’s part of me that hesitates to characterize his work in that way because I fear it implies, to some people, a lack of quality, which is not what I’m trying to convey at all. In fact, if that’s what you think it implies, then maybe you need some new best friends.

This book, specifically, asks—in every which way—what we, as individuals and as a society, might be wrong about. We look back in history and it’s obvious to us that people have always been wrong about major facts or issues at any given time, yet it’s difficult to apply that same scrutiny to the present. Chuck tries. He looks at art, science, politics, sports, dreaming, the fabric of reality, and just about everything else. He consults experts in each field, and he draws some fascinating conclusions about how we think about what we know, or don’t know.

Q: How would you describe this book to someone who’s never read Chuck?

A: Imagine you’re about to meet up at a bar (or any other kind of location where you can relax and enjoy yourself) with several of your best friends. You’re going to discuss both important and completely unimportant subjects. You’re going to play some songs on the jukebox, which might lead you to ponder the career of Gerry Rafferty. You’re going to casually watch whatever games are on. You’ll argue, you’ll laugh—both with and at each other—and you might be surprised by a good friend’s revelation or news. And, unless someone loses a tooth or a credit card, you’ll have a good time, living in a world where not all times are good.

Reading Chuck is the literary equivalent of that night out. There’s part of me that hesitates to characterize his work in that way because I fear it implies, to some people, a lack of quality, which is not what I’m trying to convey at all. In fact, if that’s what you think it implies, then maybe you need some new best friends.

This book, specifically, asks—in every which way—what we, as individuals and as a society, might be wrong about. We look back in history and it’s obvious to us that people have always been wrong about major facts or issues at any given time, yet it’s difficult to apply that same scrutiny to the present. Chuck tries. He looks at art, science, politics, sports, dreaming, the fabric of reality, and just about everything else. He consults experts in each field, and he draws some fascinating conclusions about how we think about what we know, or don’t know.

Q: What would surprise a layman about the editing and publishing process?

A: People who are unfamiliar with the publishing industry probably don’t realize the extent to which editors are involved in a book at every step from signing it up to editing it (they probably can guess about that part) to publishing it to finding ways to promote it years later. Editors depend on countless colleagues in production, design, sales, publicity, marketing, rights, and legal—not to mention booksellers and media and partners outside of the publishing house—but an editor is generally involved throughout the entire process. An editor is the author’s primary connection to the publishing house. Maybe a layman knows all of this. Sometimes that guy is smarter than we think.

Q: What do you look for when you acquire a book? How does that apply to But What if We’re Wrong?

A: It’s relatively simple: I look for books I love to read. Of course, I have particular interests in music, pop culture, sports, counterculture, and quirky/weird/wild subjects, so most of the books I look for relate to one or more of those realms, but I also love a writer who can pull me into a subject I was never expecting to want to read about. That takes a distinct voice and command of language, and usually some sense of levity, which can range from subtle to outlandish.

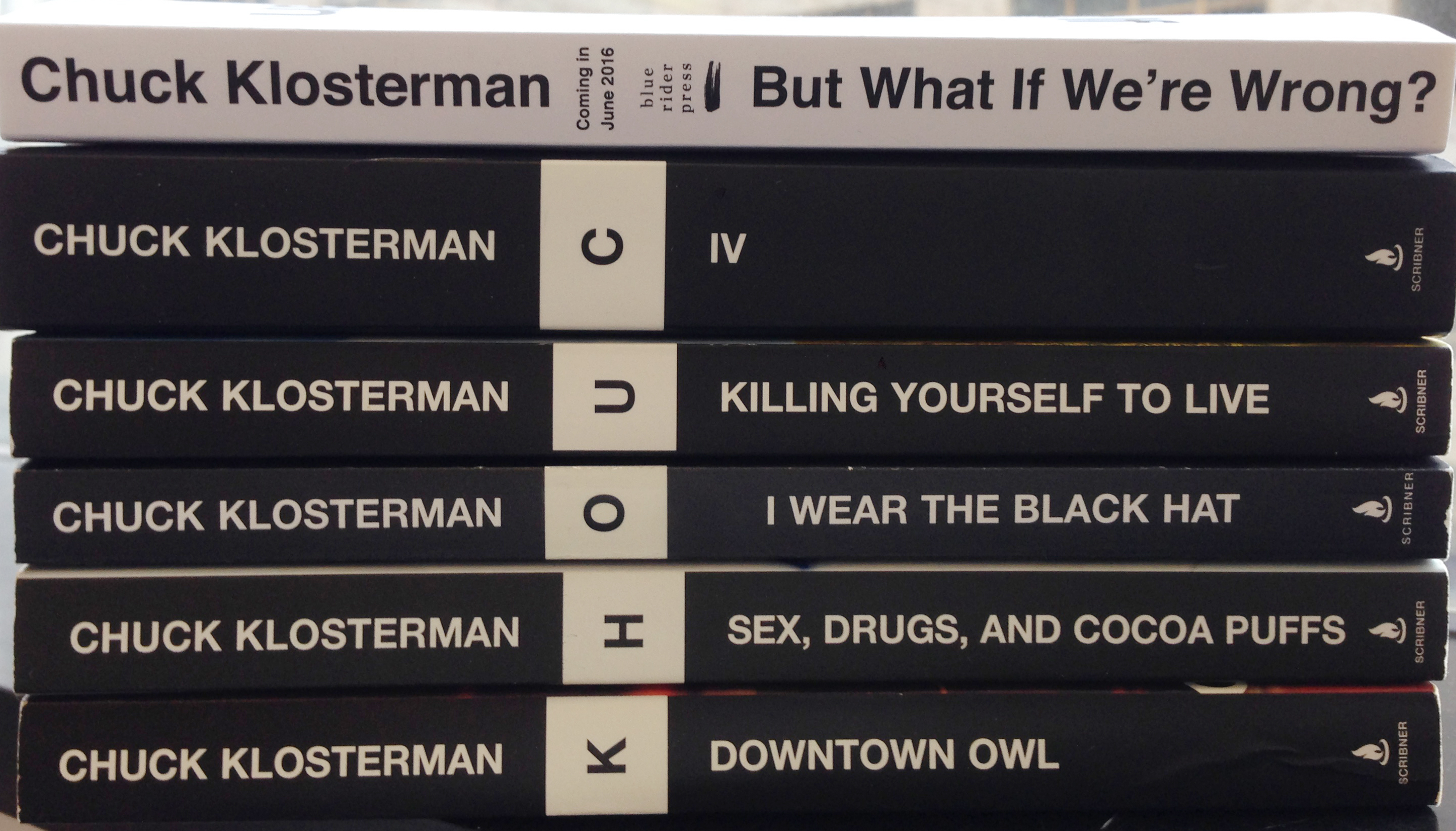

As for Chuck, I’ve been working with him since the beginning of his literary career, which was essentially the beginning of my career as an editor. In 1999, I was a novice editor, but I’d been trained to look for writers and books, applying the aforementioned principles, and I’m extremely fortunate to have been in the right place at the right time to start working with Chuck. The way in which he typifies the kind of writer I enjoy reading cannot be overstated.

Q: What would surprise a layman about the editing and publishing process?

A: People who are unfamiliar with the publishing industry probably don’t realize the extent to which editors are involved in a book at every step from signing it up to editing it (they probably can guess about that part) to publishing it to finding ways to promote it years later. Editors depend on countless colleagues in production, design, sales, publicity, marketing, rights, and legal—not to mention booksellers and media and partners outside of the publishing house—but an editor is generally involved throughout the entire process. An editor is the author’s primary connection to the publishing house. Maybe a layman knows all of this. Sometimes that guy is smarter than we think.

Q: What do you look for when you acquire a book? How does that apply to But What if We’re Wrong?

A: It’s relatively simple: I look for books I love to read. Of course, I have particular interests in music, pop culture, sports, counterculture, and quirky/weird/wild subjects, so most of the books I look for relate to one or more of those realms, but I also love a writer who can pull me into a subject I was never expecting to want to read about. That takes a distinct voice and command of language, and usually some sense of levity, which can range from subtle to outlandish.

As for Chuck, I’ve been working with him since the beginning of his literary career, which was essentially the beginning of my career as an editor. In 1999, I was a novice editor, but I’d been trained to look for writers and books, applying the aforementioned principles, and I’m extremely fortunate to have been in the right place at the right time to start working with Chuck. The way in which he typifies the kind of writer I enjoy reading cannot be overstated.

Q: What’s the first thing you do after acquiring a book? How do you start the editing process? How do you collaborate with Chuck? How has it changed since his first book?

A: Usually, in the process of acquiring a book, an editor has had some kind of conversation with the author. So, the first step is usually an extension of that conversation, and just getting to know each other a little bit. If the writer is in New York, I take him or her to lunch. We talk about logistics of the project and the general approach the writer is going to take with the book.

With Chuck, this is the eighth book we’ve worked on together, and we know each other well. We’re pals who’ve watched approximately fifty college football games while sitting in the same room. But I still take him to lunch sometimes. We usually have three big conversations about a given book—one before he starts writing, one after he’s been writing for a while, and one before he delivers the first complete draft. Then we have lots of little conversations and email exchanges until the book is ready to go to the printer. That hasn’t changed a lot over the years.

Check back soon for Part 2., in which Rumble describes his favorite parts of the editorial process and the most striking chapters of But What If We’re Wrong?.

Read the first post in this series here.

Q: What’s the first thing you do after acquiring a book? How do you start the editing process? How do you collaborate with Chuck? How has it changed since his first book?

A: Usually, in the process of acquiring a book, an editor has had some kind of conversation with the author. So, the first step is usually an extension of that conversation, and just getting to know each other a little bit. If the writer is in New York, I take him or her to lunch. We talk about logistics of the project and the general approach the writer is going to take with the book.

With Chuck, this is the eighth book we’ve worked on together, and we know each other well. We’re pals who’ve watched approximately fifty college football games while sitting in the same room. But I still take him to lunch sometimes. We usually have three big conversations about a given book—one before he starts writing, one after he’s been writing for a while, and one before he delivers the first complete draft. Then we have lots of little conversations and email exchanges until the book is ready to go to the printer. That hasn’t changed a lot over the years.

Check back soon for Part 2., in which Rumble describes his favorite parts of the editorial process and the most striking chapters of But What If We’re Wrong?.

Read the first post in this series here.

From the Editor’s Desk: Carole Baron, editor of Maeve Binchy’s A Few of the Girls

The Life of a Book: From Manuscript to Bookstore

Chuck Klosterman is an author and essayist known for his books (Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs, Eating the Dinosaur, and Fargo Rock City, among others), and his columns and articles for GQ, Esquire, Grantland, Spin, and The New York Times Magazine. His newest book, But What If We’re Wrong?, coming out this June, is all about the supposed facts and knowledge we take for granted.

Check back in the coming weeks for the inside scoop from Chuck’s editor, Brant Rumble.

Chuck Klosterman is an author and essayist known for his books (Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs, Eating the Dinosaur, and Fargo Rock City, among others), and his columns and articles for GQ, Esquire, Grantland, Spin, and The New York Times Magazine. His newest book, But What If We’re Wrong?, coming out this June, is all about the supposed facts and knowledge we take for granted.

Check back in the coming weeks for the inside scoop from Chuck’s editor, Brant Rumble.

Read more about But What If We’re Wrong? below.

Read more about But What If We’re Wrong? below.

An Essay from Carole Baron, editor of Green Island by Shawna Yang Ryan

Learn more about Green Island here.

Learn more about Green Island here.