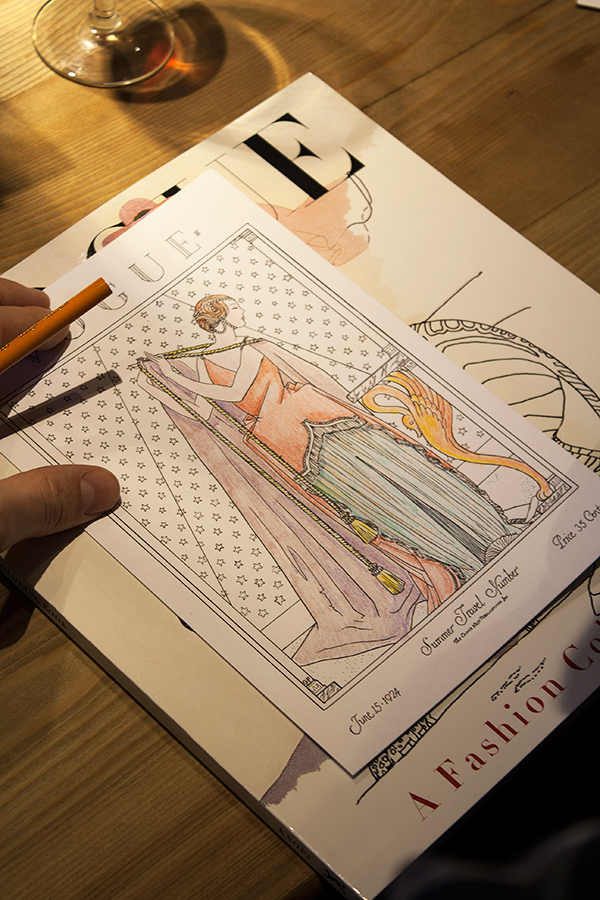

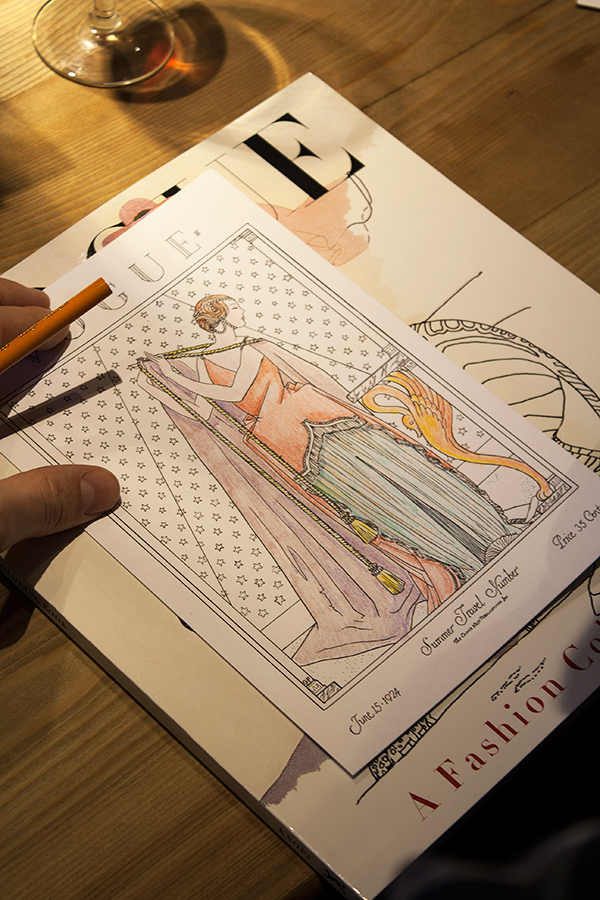

Adult coloring books have taken the world by storm. Here, Andy Hughes, (Vice President and Director of Production and Interior Design, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group) takes us behind the scenes of the new Vogue Colors A-Z.

The Vogue coloring book is my first foray into the making of what’s become a publishing phenomenon. I’ve been producing books for

Alfred A. Knopf publishing for nearly 40 years, during which time, I’ve handled every genre of book, including massive, sumptuous coffee table Vogue books (

Vogue Living, World of Vogue, Vogue Weddings), so I welcomed the opportunity and challenge to figure out how to put together a typically lower-priced interactive consumer book coupled with the prestige of the

Vogue brand.

When the idea was introduced to me in December 2015, it was soon apparent that reconstructing full-color vintage Vogue cover images into outline form would be a difficult challenge. Valerie Steiker, the Vogue Editor who conceived and assembled the project, sent Knopf’s editor, Shelley Wanger, four sample images at my request for testing. The alphabetical architecture of the book meant 26 images; when I studied them all, some of the covers were rendered simply with large mono-colored elements, others with the shadowing of garments with folds or the translucency of a diaphanous silky material, and the rest elaborated with rich details of texture and pattern. The goal of retaining the readability of the images, without the assistance of color, shading, and texture, was my immediate concern and challenge to figure out.

The first task was to de-colorize the image and delete the tonal gradations of the art. I had a pre-press vendor handle this in Photoshop, instructing them to retain as much of the skeletal outlines of the images as possible. But, the resulting image file retained just a soft, fuzzy outline, and many of the details got diminished in this filtering process. It was apparent that the services of an artist-illustrator would be needed to re-draw the art to enhance the line and embellish the image to suggest volume and delineate areas of detail for the colorist to fill in. A young, fashionable colleague of mine suggested her aunt, Cecilia Lehar, who did just this sort of inking. So, I wrote Cecilia, who years ago had coincidentally worked on

Vogue patterns for 11 years, and worked on an exhibition, 250 years of Fashion, for the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I reviewed her portfolio, and asked her to prepare a line art version of the four pieces I had de-colorized. Her initial work was excellent: faithful to the original, yet now as a line rendering that could be successfully filled in with colors.

From that moment on, for the next month, it was meetings at Vogue and in my office to review the ensuing progress of Cecilia’s re-work of all the illustrated covers and incidental art throughout. In the book, each cover appears on the right side page of a spread, faced on the left page with the letter of the alphabet that corresponds to some element or theme of the cover image. Initially, the Vogue Deputy Design Director, Alberto Orta, chose a period-appropriate “Deco” border motif surrounding the letter of the alphabet, dramatic with contrasting black and white panels. We realized quickly that any solid filled-in area needed to be “emptied” to only an outline so another element of the book could be filled in with color by the book’s owner. And, each letter is further decorated by drawings evocative of the letter and cover image, which also needed to be re-drawn as line art. So, as the book took form, we added more and more colorable areas.

The book also includes a six-page barrel gatefold insert, perforated for removal from the book, comprised of 21 appareled models, consecutively arranged, representing the years 1912-1932. Again, each figure required re-drawing and refinements making them suitable for coloring. The cover of this paperback book features six-inch flaps (more figures to color!), and printed on the verso side of the cover, an array of the same decorative drawings that punctuate each letter within the book.

Manufacturing a book equal to the quality of Vogue’s historical covers required extensive research to identify the ideal paper to print on. The paper’s brightness, opacity and surface smoothness were all considered carefully, and finally, a 120-pound text (aka 65-pound cover) Accent Opaque paper was deemed perfect, but the next challenge was to make sure paper this thick could be folded well on the press equipment available for the large quantity of books being printed and the tight schedule we were dealing with. Press tests were conducted—luckily successful—though pushing at the limits of the equipment’s capabilities. Another embellishment to the book was including thumbnail-sized reproductions of the original covers (color elements are very uncommon in coloring books). Their reproduction was critical, and including these references of the original art allowed Valerie the opportunity to identify the cover images’ creators along with fascinating anecdotes, which further elevates

Vogue Color A-Z above other coloring books by adding fashion history, wit, and a challenge to this book’s colorist to match the original artwork.

Read below to learn more about the book!

When the idea was introduced to me in December 2015, it was soon apparent that reconstructing full-color vintage Vogue cover images into outline form would be a difficult challenge. Valerie Steiker, the Vogue Editor who conceived and assembled the project, sent Knopf’s editor, Shelley Wanger, four sample images at my request for testing. The alphabetical architecture of the book meant 26 images; when I studied them all, some of the covers were rendered simply with large mono-colored elements, others with the shadowing of garments with folds or the translucency of a diaphanous silky material, and the rest elaborated with rich details of texture and pattern. The goal of retaining the readability of the images, without the assistance of color, shading, and texture, was my immediate concern and challenge to figure out.

The first task was to de-colorize the image and delete the tonal gradations of the art. I had a pre-press vendor handle this in Photoshop, instructing them to retain as much of the skeletal outlines of the images as possible. But, the resulting image file retained just a soft, fuzzy outline, and many of the details got diminished in this filtering process. It was apparent that the services of an artist-illustrator would be needed to re-draw the art to enhance the line and embellish the image to suggest volume and delineate areas of detail for the colorist to fill in. A young, fashionable colleague of mine suggested her aunt, Cecilia Lehar, who did just this sort of inking. So, I wrote Cecilia, who years ago had coincidentally worked on Vogue patterns for 11 years, and worked on an exhibition, 250 years of Fashion, for the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I reviewed her portfolio, and asked her to prepare a line art version of the four pieces I had de-colorized. Her initial work was excellent: faithful to the original, yet now as a line rendering that could be successfully filled in with colors.

When the idea was introduced to me in December 2015, it was soon apparent that reconstructing full-color vintage Vogue cover images into outline form would be a difficult challenge. Valerie Steiker, the Vogue Editor who conceived and assembled the project, sent Knopf’s editor, Shelley Wanger, four sample images at my request for testing. The alphabetical architecture of the book meant 26 images; when I studied them all, some of the covers were rendered simply with large mono-colored elements, others with the shadowing of garments with folds or the translucency of a diaphanous silky material, and the rest elaborated with rich details of texture and pattern. The goal of retaining the readability of the images, without the assistance of color, shading, and texture, was my immediate concern and challenge to figure out.

The first task was to de-colorize the image and delete the tonal gradations of the art. I had a pre-press vendor handle this in Photoshop, instructing them to retain as much of the skeletal outlines of the images as possible. But, the resulting image file retained just a soft, fuzzy outline, and many of the details got diminished in this filtering process. It was apparent that the services of an artist-illustrator would be needed to re-draw the art to enhance the line and embellish the image to suggest volume and delineate areas of detail for the colorist to fill in. A young, fashionable colleague of mine suggested her aunt, Cecilia Lehar, who did just this sort of inking. So, I wrote Cecilia, who years ago had coincidentally worked on Vogue patterns for 11 years, and worked on an exhibition, 250 years of Fashion, for the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I reviewed her portfolio, and asked her to prepare a line art version of the four pieces I had de-colorized. Her initial work was excellent: faithful to the original, yet now as a line rendering that could be successfully filled in with colors.

From that moment on, for the next month, it was meetings at Vogue and in my office to review the ensuing progress of Cecilia’s re-work of all the illustrated covers and incidental art throughout. In the book, each cover appears on the right side page of a spread, faced on the left page with the letter of the alphabet that corresponds to some element or theme of the cover image. Initially, the Vogue Deputy Design Director, Alberto Orta, chose a period-appropriate “Deco” border motif surrounding the letter of the alphabet, dramatic with contrasting black and white panels. We realized quickly that any solid filled-in area needed to be “emptied” to only an outline so another element of the book could be filled in with color by the book’s owner. And, each letter is further decorated by drawings evocative of the letter and cover image, which also needed to be re-drawn as line art. So, as the book took form, we added more and more colorable areas.

From that moment on, for the next month, it was meetings at Vogue and in my office to review the ensuing progress of Cecilia’s re-work of all the illustrated covers and incidental art throughout. In the book, each cover appears on the right side page of a spread, faced on the left page with the letter of the alphabet that corresponds to some element or theme of the cover image. Initially, the Vogue Deputy Design Director, Alberto Orta, chose a period-appropriate “Deco” border motif surrounding the letter of the alphabet, dramatic with contrasting black and white panels. We realized quickly that any solid filled-in area needed to be “emptied” to only an outline so another element of the book could be filled in with color by the book’s owner. And, each letter is further decorated by drawings evocative of the letter and cover image, which also needed to be re-drawn as line art. So, as the book took form, we added more and more colorable areas.

The book also includes a six-page barrel gatefold insert, perforated for removal from the book, comprised of 21 appareled models, consecutively arranged, representing the years 1912-1932. Again, each figure required re-drawing and refinements making them suitable for coloring. The cover of this paperback book features six-inch flaps (more figures to color!), and printed on the verso side of the cover, an array of the same decorative drawings that punctuate each letter within the book.

Manufacturing a book equal to the quality of Vogue’s historical covers required extensive research to identify the ideal paper to print on. The paper’s brightness, opacity and surface smoothness were all considered carefully, and finally, a 120-pound text (aka 65-pound cover) Accent Opaque paper was deemed perfect, but the next challenge was to make sure paper this thick could be folded well on the press equipment available for the large quantity of books being printed and the tight schedule we were dealing with. Press tests were conducted—luckily successful—though pushing at the limits of the equipment’s capabilities. Another embellishment to the book was including thumbnail-sized reproductions of the original covers (color elements are very uncommon in coloring books). Their reproduction was critical, and including these references of the original art allowed Valerie the opportunity to identify the cover images’ creators along with fascinating anecdotes, which further elevates Vogue Color A-Z above other coloring books by adding fashion history, wit, and a challenge to this book’s colorist to match the original artwork.

Read below to learn more about the book!

The book also includes a six-page barrel gatefold insert, perforated for removal from the book, comprised of 21 appareled models, consecutively arranged, representing the years 1912-1932. Again, each figure required re-drawing and refinements making them suitable for coloring. The cover of this paperback book features six-inch flaps (more figures to color!), and printed on the verso side of the cover, an array of the same decorative drawings that punctuate each letter within the book.

Manufacturing a book equal to the quality of Vogue’s historical covers required extensive research to identify the ideal paper to print on. The paper’s brightness, opacity and surface smoothness were all considered carefully, and finally, a 120-pound text (aka 65-pound cover) Accent Opaque paper was deemed perfect, but the next challenge was to make sure paper this thick could be folded well on the press equipment available for the large quantity of books being printed and the tight schedule we were dealing with. Press tests were conducted—luckily successful—though pushing at the limits of the equipment’s capabilities. Another embellishment to the book was including thumbnail-sized reproductions of the original covers (color elements are very uncommon in coloring books). Their reproduction was critical, and including these references of the original art allowed Valerie the opportunity to identify the cover images’ creators along with fascinating anecdotes, which further elevates Vogue Color A-Z above other coloring books by adding fashion history, wit, and a challenge to this book’s colorist to match the original artwork.

Read below to learn more about the book!

Q: Do you have a favorite part of the editorial and publishing process?

A: I have a few. First, there’s the moment when you realize that you want to work on a book. It’s not unlike the beginning of a romance, minus all of the untoward activities, of course. Then there’s the editing. It’s definitely work, and sometimes it’s more work than anticipated, but, when you can shut out the world and really interact with what someone has written—ask them more questions, challenge them a bit, and just enjoy it like any reader would—that’s entertaining. It’s a heightened form of reading. And, last but not least, there are moments when you can tell that a reader (other than yourself) has genuinely loved a book. Whether it’s a rave review or a crowd of people at an author’s event who are obviously enjoying themselves, or someone on the subway reading one of your books with an intent (but not displeased) look on his or her face. I have a cynical side, like anyone else, but those are the things that have a way of eroding it, at least until the next moment of pain and disappointment comes along.

Q: Do you have a favorite part of the editorial and publishing process?

A: I have a few. First, there’s the moment when you realize that you want to work on a book. It’s not unlike the beginning of a romance, minus all of the untoward activities, of course. Then there’s the editing. It’s definitely work, and sometimes it’s more work than anticipated, but, when you can shut out the world and really interact with what someone has written—ask them more questions, challenge them a bit, and just enjoy it like any reader would—that’s entertaining. It’s a heightened form of reading. And, last but not least, there are moments when you can tell that a reader (other than yourself) has genuinely loved a book. Whether it’s a rave review or a crowd of people at an author’s event who are obviously enjoying themselves, or someone on the subway reading one of your books with an intent (but not displeased) look on his or her face. I have a cynical side, like anyone else, but those are the things that have a way of eroding it, at least until the next moment of pain and disappointment comes along.

Q: Do you have a favorite section or quote from But What if We’re Wrong?

Q: Do you have a favorite section or quote from But What if We’re Wrong?

Penguin Random House has been a longstanding supporter of Poets & Writers and was well-represented at this event, where Paul was surrounded by many of his closest literary colleagues from over the years, including such Viking/Penguin authors as Sue Monk Kidd, whose introductory remarks included these wonderful words: “When I started to think about how to describe my experience working with Paul, the first word that came to my mind was brilliant. Paul brings a prodigious amount of smarts to the table, and I’m not just talking about his intellect, his knowledge or his logistical thinking, I’m also talking about his very intuitive and inventive wisdom. The other word that comes to me when I think about Paul is thoughtful. He’s one of the most thoughtful people that I know, and by this I mean that he also brings a lot of sensitivity and availability and attentiveness to his authors, so his exceptional brilliance and his exceptional thoughtfulness combined with his very tranquil demeanor is just an exquisite combination. And I think it has helped my own writing to flourish, whether it’s writing about something that keeps me up at night like American slavery or whether it’s pursuing an idea for my next novel that is patently insane, I take comfort in knowing that Paul is there.”

Penguin Random House has been a longstanding supporter of Poets & Writers and was well-represented at this event, where Paul was surrounded by many of his closest literary colleagues from over the years, including such Viking/Penguin authors as Sue Monk Kidd, whose introductory remarks included these wonderful words: “When I started to think about how to describe my experience working with Paul, the first word that came to my mind was brilliant. Paul brings a prodigious amount of smarts to the table, and I’m not just talking about his intellect, his knowledge or his logistical thinking, I’m also talking about his very intuitive and inventive wisdom. The other word that comes to me when I think about Paul is thoughtful. He’s one of the most thoughtful people that I know, and by this I mean that he also brings a lot of sensitivity and availability and attentiveness to his authors, so his exceptional brilliance and his exceptional thoughtfulness combined with his very tranquil demeanor is just an exquisite combination. And I think it has helped my own writing to flourish, whether it’s writing about something that keeps me up at night like American slavery or whether it’s pursuing an idea for my next novel that is patently insane, I take comfort in knowing that Paul is there.”

Q: How would you describe this book to someone who’s never read Chuck?

A: Imagine you’re about to meet up at a bar (or any other kind of location where you can relax and enjoy yourself) with several of your best friends. You’re going to discuss both important and completely unimportant subjects. You’re going to play some songs on the jukebox, which might lead you to ponder the career of Gerry Rafferty. You’re going to casually watch whatever games are on. You’ll argue, you’ll laugh—both with and at each other—and you might be surprised by a good friend’s revelation or news. And, unless someone loses a tooth or a credit card, you’ll have a good time, living in a world where not all times are good.

Reading Chuck is the literary equivalent of that night out. There’s part of me that hesitates to characterize his work in that way because I fear it implies, to some people, a lack of quality, which is not what I’m trying to convey at all. In fact, if that’s what you think it implies, then maybe you need some new best friends.

This book, specifically, asks—in every which way—what we, as individuals and as a society, might be wrong about. We look back in history and it’s obvious to us that people have always been wrong about major facts or issues at any given time, yet it’s difficult to apply that same scrutiny to the present. Chuck tries. He looks at art, science, politics, sports, dreaming, the fabric of reality, and just about everything else. He consults experts in each field, and he draws some fascinating conclusions about how we think about what we know, or don’t know.

Q: How would you describe this book to someone who’s never read Chuck?

A: Imagine you’re about to meet up at a bar (or any other kind of location where you can relax and enjoy yourself) with several of your best friends. You’re going to discuss both important and completely unimportant subjects. You’re going to play some songs on the jukebox, which might lead you to ponder the career of Gerry Rafferty. You’re going to casually watch whatever games are on. You’ll argue, you’ll laugh—both with and at each other—and you might be surprised by a good friend’s revelation or news. And, unless someone loses a tooth or a credit card, you’ll have a good time, living in a world where not all times are good.

Reading Chuck is the literary equivalent of that night out. There’s part of me that hesitates to characterize his work in that way because I fear it implies, to some people, a lack of quality, which is not what I’m trying to convey at all. In fact, if that’s what you think it implies, then maybe you need some new best friends.

This book, specifically, asks—in every which way—what we, as individuals and as a society, might be wrong about. We look back in history and it’s obvious to us that people have always been wrong about major facts or issues at any given time, yet it’s difficult to apply that same scrutiny to the present. Chuck tries. He looks at art, science, politics, sports, dreaming, the fabric of reality, and just about everything else. He consults experts in each field, and he draws some fascinating conclusions about how we think about what we know, or don’t know.

Q: What would surprise a layman about the editing and publishing process?

A: People who are unfamiliar with the publishing industry probably don’t realize the extent to which editors are involved in a book at every step from signing it up to editing it (they probably can guess about that part) to publishing it to finding ways to promote it years later. Editors depend on countless colleagues in production, design, sales, publicity, marketing, rights, and legal—not to mention booksellers and media and partners outside of the publishing house—but an editor is generally involved throughout the entire process. An editor is the author’s primary connection to the publishing house. Maybe a layman knows all of this. Sometimes that guy is smarter than we think.

Q: What do you look for when you acquire a book? How does that apply to But What if We’re Wrong?

A: It’s relatively simple: I look for books I love to read. Of course, I have particular interests in music, pop culture, sports, counterculture, and quirky/weird/wild subjects, so most of the books I look for relate to one or more of those realms, but I also love a writer who can pull me into a subject I was never expecting to want to read about. That takes a distinct voice and command of language, and usually some sense of levity, which can range from subtle to outlandish.

As for Chuck, I’ve been working with him since the beginning of his literary career, which was essentially the beginning of my career as an editor. In 1999, I was a novice editor, but I’d been trained to look for writers and books, applying the aforementioned principles, and I’m extremely fortunate to have been in the right place at the right time to start working with Chuck. The way in which he typifies the kind of writer I enjoy reading cannot be overstated.

Q: What would surprise a layman about the editing and publishing process?

A: People who are unfamiliar with the publishing industry probably don’t realize the extent to which editors are involved in a book at every step from signing it up to editing it (they probably can guess about that part) to publishing it to finding ways to promote it years later. Editors depend on countless colleagues in production, design, sales, publicity, marketing, rights, and legal—not to mention booksellers and media and partners outside of the publishing house—but an editor is generally involved throughout the entire process. An editor is the author’s primary connection to the publishing house. Maybe a layman knows all of this. Sometimes that guy is smarter than we think.

Q: What do you look for when you acquire a book? How does that apply to But What if We’re Wrong?

A: It’s relatively simple: I look for books I love to read. Of course, I have particular interests in music, pop culture, sports, counterculture, and quirky/weird/wild subjects, so most of the books I look for relate to one or more of those realms, but I also love a writer who can pull me into a subject I was never expecting to want to read about. That takes a distinct voice and command of language, and usually some sense of levity, which can range from subtle to outlandish.

As for Chuck, I’ve been working with him since the beginning of his literary career, which was essentially the beginning of my career as an editor. In 1999, I was a novice editor, but I’d been trained to look for writers and books, applying the aforementioned principles, and I’m extremely fortunate to have been in the right place at the right time to start working with Chuck. The way in which he typifies the kind of writer I enjoy reading cannot be overstated.

Q: What’s the first thing you do after acquiring a book? How do you start the editing process? How do you collaborate with Chuck? How has it changed since his first book?

A: Usually, in the process of acquiring a book, an editor has had some kind of conversation with the author. So, the first step is usually an extension of that conversation, and just getting to know each other a little bit. If the writer is in New York, I take him or her to lunch. We talk about logistics of the project and the general approach the writer is going to take with the book.

With Chuck, this is the eighth book we’ve worked on together, and we know each other well. We’re pals who’ve watched approximately fifty college football games while sitting in the same room. But I still take him to lunch sometimes. We usually have three big conversations about a given book—one before he starts writing, one after he’s been writing for a while, and one before he delivers the first complete draft. Then we have lots of little conversations and email exchanges until the book is ready to go to the printer. That hasn’t changed a lot over the years.

Check back soon for Part 2., in which Rumble describes his favorite parts of the editorial process and the most striking chapters of But What If We’re Wrong?.

Read the first post in this series

Q: What’s the first thing you do after acquiring a book? How do you start the editing process? How do you collaborate with Chuck? How has it changed since his first book?

A: Usually, in the process of acquiring a book, an editor has had some kind of conversation with the author. So, the first step is usually an extension of that conversation, and just getting to know each other a little bit. If the writer is in New York, I take him or her to lunch. We talk about logistics of the project and the general approach the writer is going to take with the book.

With Chuck, this is the eighth book we’ve worked on together, and we know each other well. We’re pals who’ve watched approximately fifty college football games while sitting in the same room. But I still take him to lunch sometimes. We usually have three big conversations about a given book—one before he starts writing, one after he’s been writing for a while, and one before he delivers the first complete draft. Then we have lots of little conversations and email exchanges until the book is ready to go to the printer. That hasn’t changed a lot over the years.

Check back soon for Part 2., in which Rumble describes his favorite parts of the editorial process and the most striking chapters of But What If We’re Wrong?.

Read the first post in this series

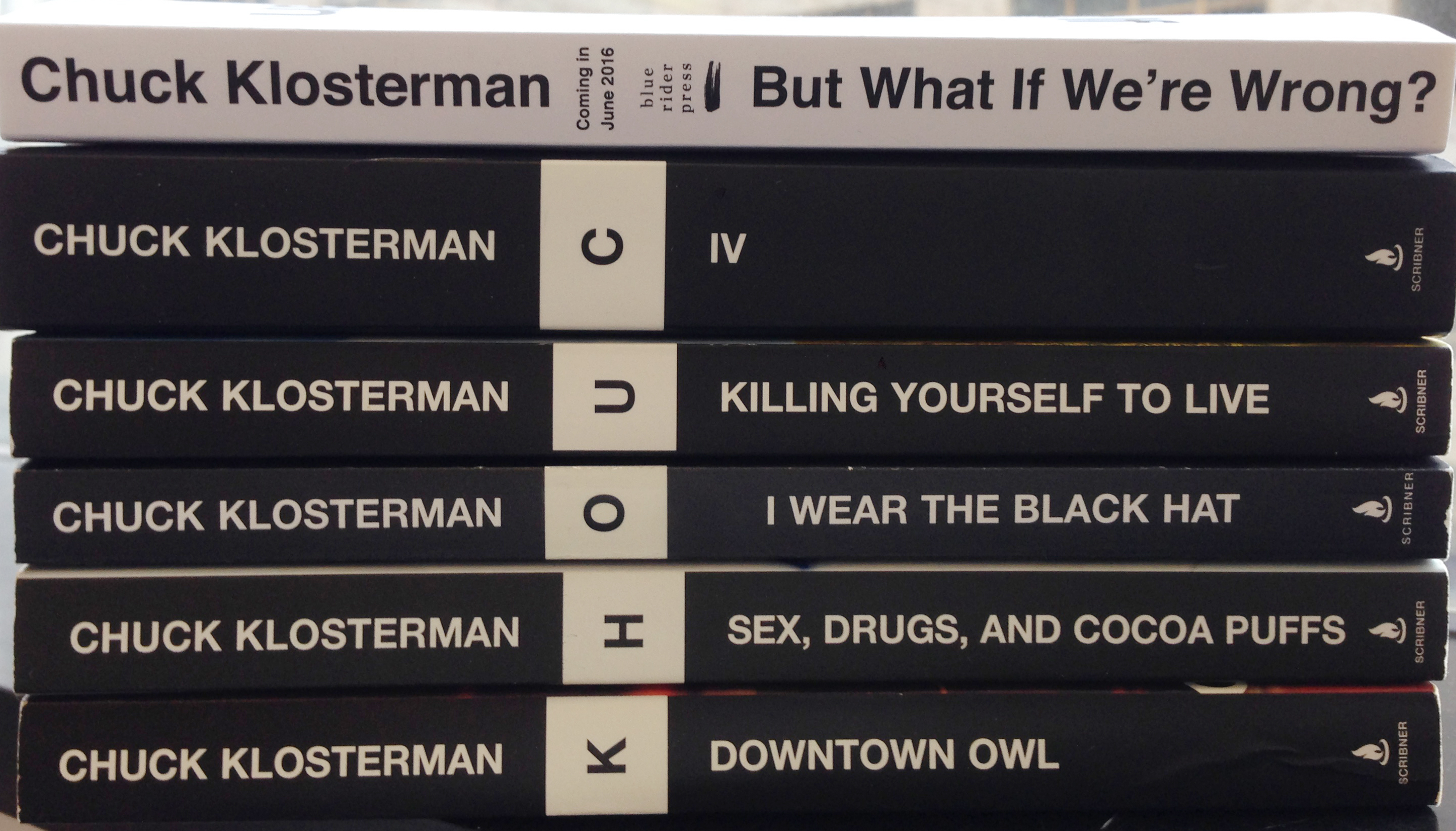

Chuck Klosterman is an author and essayist known for his books (Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs, Eating the Dinosaur, and Fargo Rock City, among others), and his columns and articles for GQ, Esquire, Grantland, Spin, and The New York Times Magazine. His newest book,

Chuck Klosterman is an author and essayist known for his books (Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs, Eating the Dinosaur, and Fargo Rock City, among others), and his columns and articles for GQ, Esquire, Grantland, Spin, and The New York Times Magazine. His newest book,  Read more about But What If We’re Wrong? below.

Read more about But What If We’re Wrong? below.

Learn more about Green Island here.

Learn more about Green Island here.

Alissa, in Crown production, is reading My Brilliant Friend, by Elena Ferrante.

Alissa, in Crown production, is reading My Brilliant Friend, by Elena Ferrante.